Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

It happens to everyone. You lose something really important, such as your keys or reading glasses, and spend hours looking everywhere — only to find it’s in the one spot you didn’t think to check.

Family history research can be a lot like that. After scouring countless archives and databases, foraging through mountains of family papers and interviewing every relative who’ll give you the time of day, you assume what’s absent from your pedigree is lost forever. But you don’t realize the details you’re after may be someplace you’ve overlooked: wills and probate.

A will, of course, is a person’s final testament about what should be done with his estate after his death. Probate is the legal court process — and the resulting documentation — to distribute a deceased person’s estate. Together, they can be the key to unlocking closed doors in family history research. These documents illustrate not only who left what to whom, but also can reveal whether your ancestors were farmers or blacksmiths; if they had enough money to lend some to the neighbors (or if they were on the borrowing side of the fence); or even if your third-great-grandfather thought his son-in-law was a good-for-nothing.

So stop looking for family history answers in the same old places and start probing into probate: Our six-step guide will show you how to find the family history riches your ancestors bequeathed to you.

1. Get an overview.

“Probate is a process, not a single event,” says Michael Leclerc, director of special projects for the New England Historic Genealogical Society. “It’s important to understand the stages of the process and the laws in that time and place.”

Probate begins when an heir, creditor or some other interested party petitions the court for the right to settle an estate. If the deceased left a will, he or she is said to have died “testate.” In this case, the purpose of the probate process is to authenticate the will and ensure the executor named in it carries out its directives. If there’s no will, the person died “intestate,” and probate serves to appoint an administrator to act as executor and distribute assets according to the law.

In either case, within a few months of an ancestor’s death, court-appointed individuals with no claim to the property took an inventory of the estate and gave the court a list of everything owned by and all debts owed to the estate. Potential beneficiaries were notified and notices placed in newspapers to reach those who might have claims or owe debts to the estate. After the settlement of bills and debts, the estate was distributed as outlined in the will. Without a valid will, relatives generally received any property.

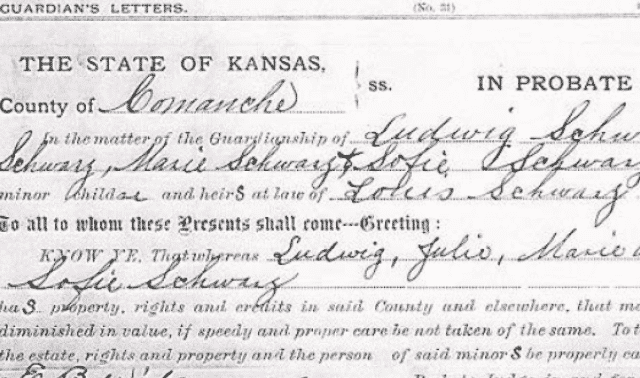

Courts keep probate records, which, along with subsequent documents related to the estate, constitute a probate packet. When the estate was finally settled — which could take until the youngest child reached adulthood — the probate court received a statement of the account and ruled the estate closed. A county clerk copied an abstract of the file into a record book, also called a copybook, and filed the probate packet. What you’ll find in it varies by state, county and time period, but it’ll likely contain a mix of these documents:

- will

- documentation of the appointment of executors or administrators

- estate inventories or lists of assets

- copies of published death notices

- documentation of asset distribution, including receipts for money or property

- list of who bought various items at an estate sale

- petitions for guardianship of children

- list of heirs and their relationships to the deceased

- lists of creditors or accounts of debts

2. Learn the laws.

You probably want to jump right in and start finding records. But it’s easy to get sidetracked or misinterpret records if you’re unfamiliar with probate and estate laws for the area and time.

For example, if you know married women couldn’t file wills without their husbands’ permission before the 20th century, you might alter your fruitless search for Great-grandma’s will (widows, though, didn’t need an OK). Female heirs’ bounty went to their husbands, so an ancestor who disliked his son-in-law might’ve circumvented the law by leaving money to his grandchildren rather than his daughter. A will might seem to ignore the eldest son, when it’s really recognizing the practice of primogeniture, in which land automatically went to the firstborn male heir unless otherwise stated in the will. You also might learn relationship terms were used differently, for example, father-in-law may refer to a stepfather, or cousin to a niece or nephew.

Especially for Colonial times, you can learn about state probate laws online at the state archives website or Bob’s Genealogy Filing Cabinet. For later eras, visit a law library or consult a book such as A History of American Law, third edition, by Lawrence M. Friedman (Touchstone).

3. Locate the right repository.

The first step to finding wills and probate is determining where the records were filed. Many researchers mistakenly look for probate files only where someone died or was buried. But probate is filed in the county courthouse or town hall where the deceased owned property or last resided — not necessarily where he died. Another common error is assuming you can do all your probate research online. “You’re not going to find that information on the Internet,” says Christine Rose, an expert in repository research and author of The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Genealogy, second edition (Alpha). “You really have to get into the courthouse records.”

But what you can do on the Internet is find out where the county keeps old probates. There’s no hard-and-fast rule. Most states file records at the local courthouse by probate district or county, and sometimes by town, says Leclerc. Many places have separate county probate courts. Elsewhere, such as Rhode Island, probate is in town halls. Probate districts may have changed over time, and some courts may have sent old records to the state archives.

To add to the challenge, you’ll find probate courts and records called by different names in different state. In New York, they’re surrogates courts; Louisiana calls them succession records and puts them in district courts; and in Mississippi, wills are in chancery court. For help sorting it out, try a Google search on the county name and “probate records” (court Web sites often list their holdings with contact information) or check the state archives website for a guide like Connecticut’s. You also can use a reference such as The Family Tree Resource Book for Genealogists edited by Sharon DeBartolo Carmack and Erin Nevius (Family Tree Books).

4. Look for an index.

Not all probate records are indexed or microfilmed, but if you can find an index online or in a book, you’ll learn the estate settlement date and the probate packet’s location in the court’s files. Since an estate could take years to settle, check the index for several decades after the death.

The county or state archives website might have a probate index. Also explore the links on Cyndi’s List. Check libraries and online for indexes such as Genealogical Publishing Co.’s North Carolina Wills, 1665-1900 CD.

A local library, the Family History Library (FHL) or the courthouse itself might have microfilmed indexes. To find an FHL index, go to the online catalog and run a place search on the county name, then look for a probate index heading (also check under court records in case the county’s court records all got lumped together). Click it to see the FHL’s microfilm. When you find the right title, click Film Notes to locate the roll number you need.

5. Visit the courthouse.

If you live near the courthouse or town hall, you easily can go there to find the records, which may be on paper or microfilm. Beware film may show a copybook instead of the original file. Not only do copybooks lack all the documents in the file, but a clerk may have copied something wrong. If you’re looking at a copybook, ask to see the originals.

Call the courthouse before you visit to find out about any special closures or restrictions. And if the records are in off-site storage, the court staff can retrieve them so they’re waiting when you arrive. Live clear across the state or country? The fastest way to get the records may be through the FHL. Again, run a place search of the online catalog and look for a probate records heading. If you can’t find microfilm of the records, you’ll need to write the courthouse or whatever repository holds the originals.

6. Read the records.

Now it’s time to dig into the documents. “There’s a huge amount of information in probate records that’s both glaringly obvious and hidden,” Leclerc says.

Family connections are among the most apparent details, including names of adult children and their spouses, and relatives designated as children’s guardians. Note all the names in the probate packet: You’ll want to research those people and look at their probate files, too. Also helpful is the date of death, which probably appears on the petition to administer the estate. If not, estimate it from the dates of the will (if there is one) and probate. Burial instructions or money left to a church or other group shows the deceased’s religious and social affiliations.

One source of “hidden” answers is the estate inventory, which gives a sense of how your ancestor lived. His possessions might reveal his occupation, economic status, religious practices and ability to read. Compare the inventory to others from the area and time for a more-thorough picture. “When you get into the early [probate files],” says Rose, “you realize the scarcity of belongings in that time. Each item was so precious.”

A will might outline exactly how to divide a home, adds Rose. For example, a man might leave his house to his sons, but designate rooms for his widow and direct the sons to ensure she had firewood.

What — or who — isn’t in the will also speaks volumes. But don’t assume a child has fallen out of favor if she isn’t named or gets only a token. The child may have died or have already collected her inheritance, such as a daughter who’d received a marriage dowry. Your ancestor’s will might state his values — today such statements are more common and are often called ethical wills.

Don’t make your ancestor’s will the last place you look for genealogy answers. Take these steps as soon as you have an inkling where and when his will was filed or his estate probated. You may find the missing pieces you’ve been searching for.

Consider an Ethical Will

Wish you could learn who your ancestors actually were, beyond just the facts? You can ensure your descendants know a whole lot more about you — if you join the growing number of Americans who are creating ethical wills.

“An ethical will is a letter or statement about your values or what has meaning in your life,” says Donna Gold, a personal historian who conducts workshops on how to prepare such documents.

Also known as a legacy letter or life letter, an ethical will leaves your heirs more than just money or property. You can use it to share family stories or words of wisdom, to explain why you left the good china to your daughter and the Matchbox car collection to your third cousin, or to tell your children or grandchildren what you couldn’t — or didn’t want to — while you were alive.

The Torah first described ethical wills some 3,000 years ago, and the Bible also contains references. While generations have long passed down family history and values orally, today’s legacy letters do the job in writing. “People are realizing there’s an absence,” Gold says about why written ethical wills are becoming more common. “Perhaps it’s that we’re more scattered and we’re not getting those stories.”

Want to make sure your descendants don’t miss out? Gold suggests attending a class or a workshop on ethical wills, reading a how-to book or just starting to write. Once you’ve prepared the document, store it in a secure location such as a safety deposit box or with your lawyer. Or you might share it with friends and family while you’re alive.

“I think it’s important to actually put it in writing in a document that is as valued as the will is,” says Gold. “It’s a continuum of family.”

Deciphering Old Probate Documents

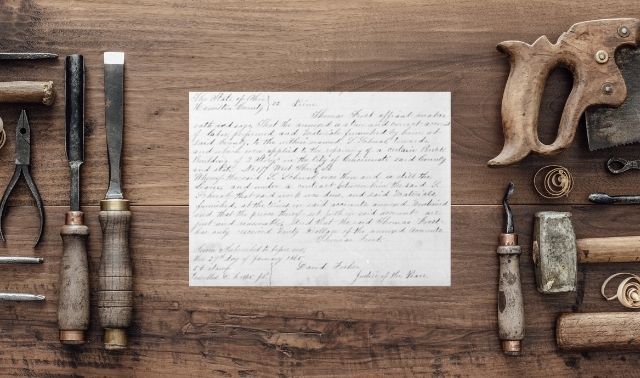

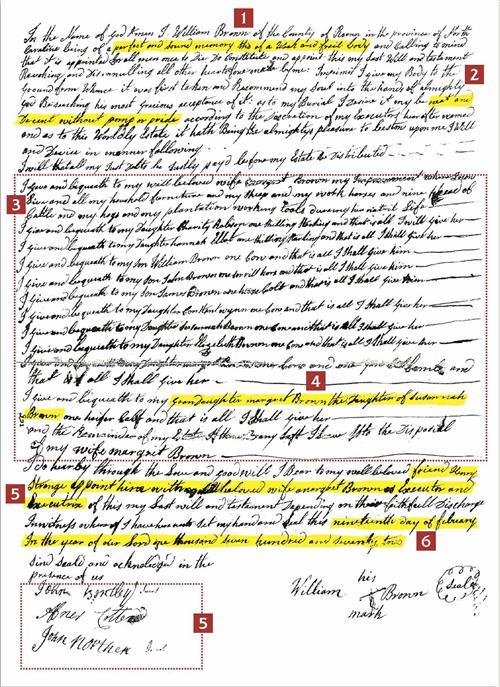

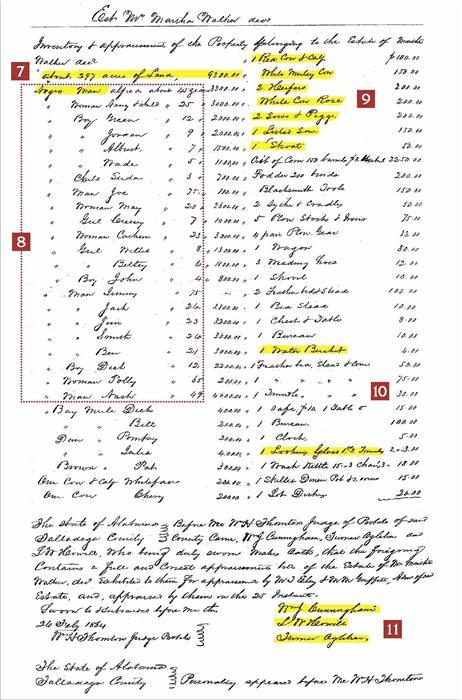

You can learn a lot from probate documents. We’ll use this 1772 will (first) and 1864 estate inventory (second) to show you what to look for.

- This familiar phrase establishes the author, William Brown, was of sound judgment—if not in good health—at the will’s writing.

- A will may specify how or where the writer is to be buried.

- William’s heirs include his wife, three sons, six daughters and a granddaughter.

- Daughter Susannah may be widowed, be married to another person named Brown, or have had daughter Margaret out of wedlock.

- The executor or executors may be named at the beginning or end of the will. Witnesses signed at the end.

- The date the will was filed, Feb. 19, 1772, may or may not be close to the date the estate was probated.

- Martha Walker was relatively well off, owning nearly 300 acres of land worth $9,300.

- Antebellum plantation owners’ inventories list slaves among the deceased’s property, making them good resources for African American research.

- Cows and pigs were among Walker’s possessions.

- Inventories list even small items, such as a $4 bucket and $3 mirrors.

- The inventory takers swear the list is a full accounting of the deceased’s property. This statement also names the estate administrators and gives the date the inventory was fi led in court.

A version of this article appeared in the September 2008 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

ADVERTISEMENT