Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

According to my mother, my great-grandfather didn’t like to talk about his experiences fighting in the Civil War. He told the family he’d been a drummer boy for the Confederacy and left it at that. Only after his death did the truth come out: At 16, Great-grandpa lied about his age and enlisted in the 37th Alabama Infantry, ultimately seeing brutal action at the battles of Corinth and Chattanooga. But today, I can find a record of his service simply by searching the Civil War Soldiers and Sailors System (CWSS), the National Park Service’s recently completed online database of 6.3 million soldier names. A few clicks, and there’s my great-grandfather’s secret for all the world to see.

Similar information on military ancestors from just about any era awaits genealogical researchers both on- and offline. Most everyone has at least one relative who was a soldier, sailor, Marine or guardsman — that, plus Americans’ fascination with military history, has fueled our interest in ancestors’ service records, draft registrations, bounty-land claims, pension applications and more. So where do you scout out these records? Follow these marching orders straight to genealogical victory.

Records reconnaissance

The information in the CWSS database came from General Index Cards in the Compiled Military Service Records at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in Washington, DC. It represents just the tip of the iceberg of NARA’s information on America’s military. These records can provide crucial clues for your family history search: birth date and place, spouse’s name, place of residence at enlistment and after discharge, and even a physical description.

The Internet has an arsenal of information about military service — that’s where I learned more about my great-grandfather’s regiment. State archives and volunteer efforts (such as RootsWeb and the USGenWeb Project) are posting ever more actual records online. Missouri, for example, has a free database containing military service cards of more than 576,000 Missourians who served from the War of 1812 through World War I. Subscription Web sites such as Ancestry.com are also adding to their caches of military records. But because of military records’ centralized nature — they largely originate from the federal government — the bulk of these records remain offline at NARA. Military service records from the Revolutionary War to 1919 are at its Washington, DC, location; those from World War I to the present are at the National Personnel Records Center (NPRC), located in St. Louis.

But that doesn’t mean you have to march on the nation’s capital or the Gateway to the West. Fortunately, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ Family History Library (FHL) has many of NARA’s records on microfilm. Search the FHL’s online catalog to see what’s available.

See NARA’s guide to obtaining veterans’ records. Its Order Online system makes it easy to request service records; you can charge the fees to a major credit card and avoid messing with special forms.

First, of course, you need to know what to look for. Since the US didn’t have a large standing army until the 20th century, most historical military records revolve around specific wars. What’s available depends on the war your ancestor served in. You also can deploy the pension records — a great way to find out more about the soldier’s family — that evolved in the aftermath of each conflict. A few other varieties of military paperwork, such as draft records, can be useful, too. Following are highlights of what you can find on your fighting ancestors for each major war.

Colonial Wars, 1675 to 1763

Since these records predate the formation of the US government, you’ll find them in state archives and historical societies. Companies such as Genealogical Publishing Co. have compiled and printed records in books — for example, Colonial Soldiers of the South, 1732-1774 or New York Colonial Muster Rolls, 1664-1775. Look for them in large public libraries’ collections or see the Genealogical Publishing Co. website. Ancestry.com’s US collection ($189 per year) includes some Colonial military record databases, such as Connecticut Soldiers in the French and Indian War and Virginia Colonial Soldiers.

Revolutionary War, 1775 to 1783

Both the available records and the genealogical information therein grow richer with America’s war for independence. The Continental Congress established America’s first army in June 1775; its commander, George Washington, supplemented the troops with Colonial militia. More than 250,000 men fought for the fledgling United States. Keep in mind, though, that your Colonial ancestor may have been a loyalist who defended the British crown, or a Tory who sympathized with Britain but didn’t bear arms.

Service records: Indexes to Revolutionary War service records, as well as the actual records, are available on microfilm at NARA, its regional facilities, and the FHL. Many major libraries have the indexes and published rosters. Subscription site Fold3 ($79.95 per year) has digitized images of Revolutionary War service records and pensions.

You also can find indexes on Ancestry.com. Use the indexes to nail down your Revolutionary War patriot’s full name, state and branch of service, then use the information to order service records from NARA or search for FHL microfilm.

Pension records and bounty-land warrants: You also can tap most of these sources for surviving Revolutionary War pension records (many early applications were lost to fires in 1800 and 1814) and records of land grants given as “bounty” to veterans in lieu of wages. Pension indexes plus the actual applications are available on microfilm at NARA and the FHL. Because the veteran or his widow had to submit various sorts of documentation to apply for a pension, the files might contain records of birth or marriage, even pages torn from family Bibles.

Similarly, claims for bounty land—which the government awarded for military service in wars up through 1855— required proof that can be genealogically valuable to you. NARA has about 450,000 bounty-land claims on file. Footnote has these land claims and pension applications online. You can search and view them free at HeritageQuest Online (accessible through subscribing libraries), though this service doesn’t contain every page from long files.

Nine states also rewarded soldiers with bounty land: Connecticut, Georgia, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, South Carolina and Virginia. See Lloyd deWitt Bockstruck’s Revolutionary War Bounty Land Grants Awarded by State Governments (Genealogical Publishing Co.) for an index to these records. Those with Virginia ancestors should also check the half-pay pension records, on microfilm at NARA and FHL, which can contain proof of heirs spanning several generations.

Lineage societies: The Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), a lineage society for women with patriot ancestors, has a library in Washington, DC, full of genealogical information. You can use the DAR’s free Patriot Lookup service to see if the organization has documented your ancestor’s military contribution (or other “patriotic service”) to the Revolution, then order copies of the files other descendants have used to prove their connection. Ancestry.com also has a searchable database of DAR lineage books spanning 152 volumes.

War of 1812, 1812 to 1815

Military service files from the War of 1812 are indexed and microfilmed at NARA. The FHL has a microfilmed index plus records for Mississippi and Ancestry.com offers a War of 1812 service records database that’s essentially an index because it lists just the soldier’s name, company and rank. Pension applications are available from NARA, but indexes to them are in books such as Virgil D. White’s Index to War of 1812 Pension Files (National Historical Publishing Co.). Look for more titles in large libraries, search the FHL’s online catalog, and see our online toolkit.

War of 1812 records also are finding their way online. Ohio, for instance, which supplied more than 26,000 soldiers, has posted the text of its adjutant general’s office rosters. If your ancestor served in the multiple Indian wars from 1815 to 1858, check the microfilmed indexes to these records at NARA or the FHL. The actual records are on microfilm at NARA.

Mexican War, 1846 to 1848

An index to records from the Mexican War is available on microfilm at NARA and the FHL (are you sensing a theme?). The actual compiled service records are microfilmed only for Arkansas, Mississippi, Pennsylvania, Tennessee and Texas, plus a special Mormon Battalion (other special units originated in New Mexico and the American Indian nations).

Congress didn’t authorize pensions for Mexican War veterans until 1887, but these application files add a few genealogical goodies: Each applicant had to supply his wife’s maiden name, the names of any former wives and related death or divorce data, and names and birth dates of living children. The applications, which were accepted until 1926, are indexed on microfilm at NARA and the FHL, but for the most part, you’ll have to request the actual files from NARA.

Civil War, 1861 to 1865

As terrible as the Civil War was, its sweeping involvement of so many Americans has benefited modern genealogists. The war produced a wealth of records, and our intense interest in the conflict has spawned countless compilations of those records, both in print and on the Web — as evidenced by the remarkable CWSS site.

But before setting out to track down your ancestor’s Civil War military records, you have to know what side he was on. Union soldiers naturally left more extensive and extant records, having fought on the winning side that had headquarters in what’s still the US capital. But what you can find about Confederate ancestors may pleasantly surprise you. You also need to know what state your ancestor enlisted from — it may not be the state where Great-great-grandpa lived when the war broke out: A volunteer may have used an enlistment center in a neighboring state if it was closer than one in his own state. Residents of border areas such as Kentucky may have jumped to Ohio or Indiana, say, to sign up for the Union cause. And don’t think that just because an ancestor lived in the heart of Dixie, he fought for the Confederacy: NARA has microfilmed records of Union Army volunteers from every Confederate state except South Carolina. Not sure which side your ancestor fought on, much less his state and military unit? That’s where the online CWSS comes in handy, with its basic information for Union and Confederate troops. (Ancestry.com has a similar database in its subscription collections.)

Service records: There are many excellent sites for exploring your Civil War ancestor’s life. You’ll find the entire Official Records — the “OR” — of the Civil War, 128 volumes in searchable digital form at eHistory and Making of America. (The massive OR, officially titled The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, is also in print at many large libraries and on microfilm at the FHL, along with an index and a companion naval series.) Many state archives and historical societies have online Civil War databases. For example, I found my great-grandfather in the Civil War index at the Alabama Department of Archives and History. Ancestry. com has state Civil War databases as well.

Fold3 has digitized compiled service records for Union (including US Colored Troops) and Confederate soldiers, taken from NARA microfilm.

You can search for your Union ancestor by state in microfilmed indexes at NARA and its regional branches, the FHL and its FHCs, and many public libraries. Soldiers in the United States Colored Troops are indexed separately. Many libraries also have a 33 volume print index called The Roster of Union Soldiers, 1861-1865. After finding your ancestor in the index, you may have to order his actual compiled service record files from NARA: Only service records from Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Missouri, Mississippi, New Mexico, North Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia and West Virginia are microfilmed and available through the FHL. NARA’s also the sole place to find records of the draft that was instituted in 1863.

Confederate service records that were captured or surrendered ended up in Washington, DC, where the War Department eventually began to compile files similar to those on Union troops. NARA has a huge microfilmed index to most of these records, spanning 535 reels grouped by state; the FHL has the index, too. Ask for the print version, The Roster of Confederate Soldiers, 1861-1865, in libraries. Many of the actual records have also been microfilmed; otherwise, you can order them from NARA once you’ve found your ancestor in the index. NARA and the FHL also have histories of Confederate regiments that can help shed light on your ancestor’s Civil War experience.

As my Alabama database search shows, state archives also keep Confederate records. It’s even possible your ancestor served in a militia whose records are kept exclusively at the state level. If you suspect that’s the case, check with state archives, historical societies and adjutant generals’ offices, and consult the FHL’s extensive collection of state Confederate records on microfilm.

Pensions: States also are your source for Confederate pension records, since the victorious Union government didn’t care to provide for the old age of the rebels. Former Confederate states that authorized pensions include Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Missouri, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia. The FHL has microfilm of many of these files, saving you a trip to the state archives.

Pension records for Union veterans are only a little easier, since many files are scattered across the country with various federal agencies that administered the pensions. Fortunately, these records are indexed, with microfilm copies available at NARA, the FHL and many public libraries (look for the General Index to Pension Files, 1861-1934 microfilm). Fold3 boasts a collection of almost 3 million index cards for approved pension applications of widows and other dependents of Civil War Union veterans. The collection is presently 99% complete. It also includes some veterans of the Spanish-American War, Philippine Insurrection and World War I.

So your quest for the application files can still begin with NARA, which will direct you to the appropriate agency if the files are not in its keeping. Union pension files are worth the paper chase, as they typically contain such genealogical gold as the veteran’s birth date and place, date and place of marriage, wife’s maiden name, and names and birth dates of their children. You may even find a physical description of your ancestor. And don’t overlook the info about the veteran’s post-discharge residences, which can help you trace a migrating ancestor as America expanded west after the war.

You can find veterans and widows of the Civil War (as well as other pre-World War I conflicts) who received pensions between 1907 and 1933 on Veterans Administration pension payment cards. These 2 million cards, arranged by the last name of the pensioner on a whopping 2,539 microfilm reels, are available at NARA and through the FHL.

Burials: In 1868, the Quartermaster General’s Office issued a Roll of Honor listing more than 228,000 Union soldiers buried during the war in some 300 national cemeteries. Genealogical Publishing Co. has republished this listing along with an index (it’s now on CD — see our tookit).

Veterans censuses: The 1890 US census included an enumeration of Union veterans (some Confederate veterans and widows are listed, too, thanks to census takers with lingering Confederate sentiments). Although most of the 1890 federal census was lost to fire, the veterans’ schedules for half of Kentucky and states beginning with L through Whave survived. You can get them on NARA microfilm; your library might have indexes. Ancestry.com has images of the census pages plus a new every-name index in its US Census Collection. Your long-lived ancestors might be listed in the 1910 census, which noted both Union and Confederate veterans.

Veterans groups: The Civil War spawned veterans groups and lineage societies for both sides. The Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) was the chief Union veterans organization, counting 40 percent of surviving veterans as members in 1890. Its national office closed in 1956, but you’ll find information and a list of posts online. Also check historical societies, state archives and libraries for GAR and similar groups’ records. The Southern equivalent, the United Confederate Veterans, published Confederate Veteran magazine from 1893 to 1932; search an online index to names in the magazine at the Library of Virginia (see this listing of the library’s records and click on Index to Confederate Veteran Magazine). Lineage societies have persisted on both sides — see the toolkit for a sampling of groups that remain active today.

Spanish-American War, 1898

Volunteers for the Spanish-American War came predominantly from New York, Illinois, Pennsylvania and Ohio; the famous Rough Riders drew heavily from New Mexico. Both NARA and the FHL have indexes to veterans’ service records and pension files; most actual records must be obtained from NARA. For online databases of card files, check the Pennsylvania State Archives (includes Revolutionary War to World War I service medal applications) and the Illinois State Archives (includes War of 1812 to Spanish-American War).

World War I, 1917 to 1918

The availability of military records for your genealogical research drops off sharply with 20th-century conflicts. Part of this is due to federal privacy regulations, which limit records access for 75 years to the veteran or, if deceased, the next of kin. Tragically for future historians and genealogists, it’s also due to a 1973 fire at the NPRC that sent approximately 18 million records up in smoke. Those include records of 80 percent of Army personnel discharged from Nov. 1, 1912, to Jan. 1, 1960; and 75 percent of Air Force personnel discharged from Sept. 25, 1947, to Jan. 1, 1964 (records of airmen with names occurring alphabetically before Hubbard, James E., weren’t burned). You can request surviving records from the NPRC using Standard Form 180 (get instructions online). WWI discharge papers also escaped the 1973 conflagration, because those veterans usually filed typed or handwritten transcripts of their papers at their hometown county courthouses.

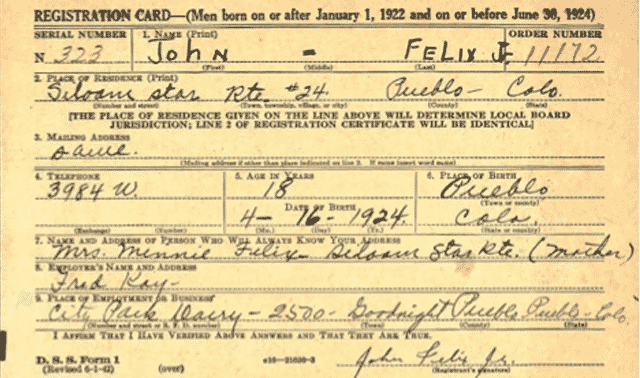

Your WWI-era ancestor may have left useful military data even if he didn’t serve. After Congress passed a draft requirement, some 24 million men born between 1872 and 1900 registered on one of four dates. That was nearly a quarter of the total US population in 1918. The draft cards are stored at NARA’s regional branch in East Point, Ga., and are available on microfilm from the FHL, and in searchable, digital form on Ancestry.com.

To find an individual on the microfilm, you need to know his name and his residence at the time of registration; for larger cities this means connecting his home location with a particular draft board — a city directory and a map of draft boards (find one on FHL microfilm 1498803) will help. The information you’ll find on the draft cards depends on which registration questionnaire your ancestor completed. Registrants on Sept. 12, 1918, for example, were required to answer 20 questions, including name, address, age, date of birth, race, citizenship status, occupation, employer’s name and address, name and address of nearest relative, and physical appearance.

World War II, 1941 to 1945; Korean War, 1950 to 1953; Vietnam War, 1961 to 1975

Federal privacy laws restrict your access to records from these recent wars, and even if you’re the veteran’s immediate family member, most were lost to fire. But you can still give it a try using NARA’s easy online eVetrecs system. You’ll have to sign an affidavit saying you’re the deceased veteran’s next of kin. WWII discharge papers were supposed to be recorded in veterans’ county courthouses, like those from World War I.

Some WWII draft registration records for the “Old Man’s Registration” of men age 45 to 64 on on April 27, 1942, are on Ancestry.com.

If your ancestor died in the Korea or Vietnam conflict, look for him or her in the Military Index CD, available at the FHL and many FHCs. You also can access these databases separately, as the Korean Conflict Death Index and the Vietnam Casualty Index, in Ancestry.com’s US Records Collection. Get NARA’s state-by-state Korean and Vietnam war casualty lists for free on the Internet.

Even with all these research possibilities, we’ve barely scratched the surface of military records. Perhaps your ancestral answers lie in veterans’ home records. Maybe your relative served in the US Merchant Marine or Coast Guard, or fought in one of the many Indian wars. The resources listed on page 31 can help you delve into these and other records. Now that your family’s military history isn’t a secret, you can declare your genealogical mission a success.

March in Step

Finding the details of your ancestor’s military service can take persistence, but the key to a breakthrough is often using different sources in tandem. Here’s how I tracked down the records of my great-grandfather William Francis “Frank” Dickinson:

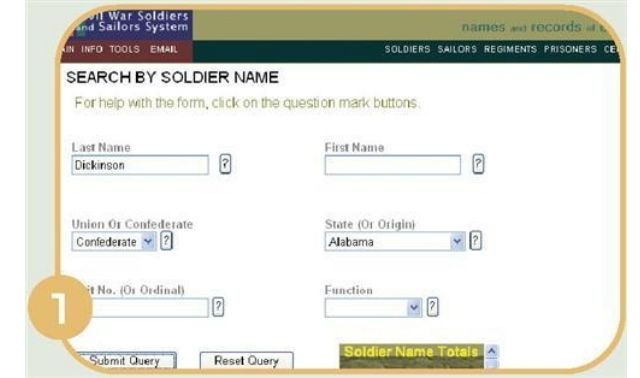

1.The Civil War Soldiers and Sailors System (CWSS) is a good place to start looking for a Union or Confederate ancestor. I left the first-name box blank on the site’s search page, since my great-grandfather might be listed as William, W.F. or even Frank.

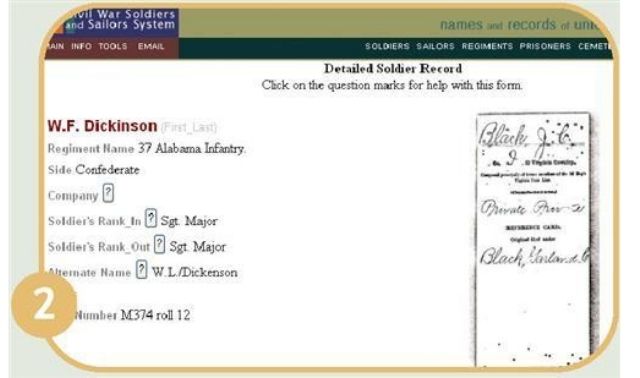

2. CWSS came up with 63 hits. When I found W.F. Dickinson, 37th Alabama Infantry, I took note of the alternate listing as W.L. Dickenson (evidently, his records were sometimes mislabeled). I also wrote down the National Archives microfilm info: M374 roll 12.

3. Learning about an ancestor’s unit can help confirm you have the right person. CWSS results link to regimental histories and rosters. The 37th was mustered at Auburn, Ala., and included men from Macon County — Frank’s home in the 1860 census. To rule out other men who could be the W.F. Dickinson in CWSS, I searched the 1860 census for that name in counties the 37th recruited from.

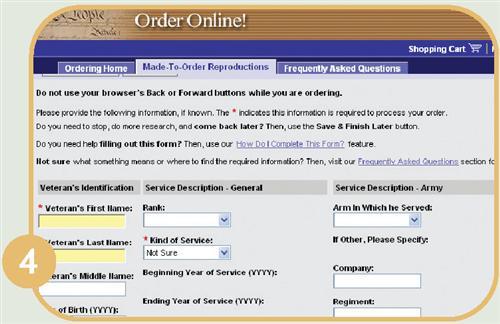

4. National Archives and Records Administration Order Online site lets you request copies of pre-WWI compiled service records, as well as applications for federal military and bounty-land warrants. A service file costs $17; delivery takes up to 90 days. The form requires only the soldier’s name, state and the war he fought in, but I filled in all I knew about W.F. Dickinson.

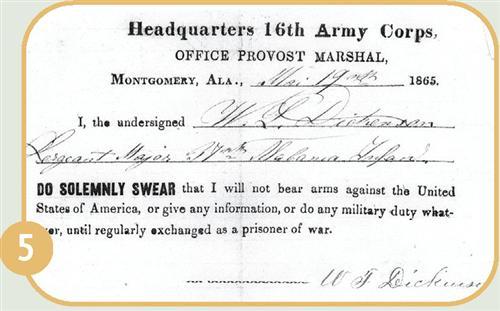

5. Compiled service files might contain records of enlistment, discharge, medical treatment and more. W.F. Dickinson’s file included an 1865 prisoner-of-war record with Frank’s description (5 feet, 5 inches tall; light hair; gray eyes; fair complexion) and his signature promising not to bear arms against the United States.

Capturing History

Did you or someone you know serve in the US military during wartime? The Library of Congress’ American Folklife Center wants those stories for the Veterans History Project, which is collecting and preserving veterans’ audio-and videotaped oral histories, along with documents such as letters, diaries, maps, photographs and home movies. Since the project began in 2000, organizers have collected more than 33,000 veterans’ stories. You can see and hear some of them — as well as search a database of more than 1,000 digitized recollections — on the Web site. Even though last year’s submissions doubled the size of the collection, the total still represents just a fraction of the estimated 25 million living veterans from World War I and beyond. Find out how to record your oral histories and submit them to the project. – Susan Wenner Jackson

Original article from the October 2005 Family Tree Magazine

ADVERTISEMENT