Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

One minute there stands in your mind’s eye a beautiful courthouse edifice, undoubtedly crammed with your ancestor’s records. The next moment is disaster: You learn there was a fire—or fires—at the courthouse. The records you needed? Gone. What can you do about those missing records?

Genealogical solutions for “burned” records—whether there was an actual fire, or the records have been lost or were never created in the first place—are neither easy nor quick. When records are missing, you have to discover new sources and methods to find the answers you seek. You’ll need creativity, perseverance and a willingness to dig into whatever records are available. Some of them probably aren’t accessible online or even in your local library. Most won’t be indexed by name, and many won’t be conveniently labeled genealogy.

This six-part process can help you discover your ancestors even when you come across missing records.

1. Understand the scope of the problem.

The first step in any crisis is not to overreact. Never make a problem bigger than it truly is. The second step is to divide the problem into parts. When you face one aspect of the problem at a time, it’ll seem more manageable. So when your research moves into a “burned” county, begin by determining the extent and magnitude of the loss.

Consider that you might’ve been misinformed, and there was no fire at all. Or perhaps a county court clerk said, “I’m sorry we can’t help you. We’ve had a courthouse fire.” You imagine all the records in an ash heap, but maybe the fire was small and consumed only some records. For instance, a 1911 fire in Albany, NY, burned thousands of records, but many have been salvaged. Therefore, you first should answer the question: Was there really a courthouse fire? If so, determine when it occurred and exactly what it destroyed.

Remember that, because many old documents aren’t readily available on the shelves, the staff may not know where they’re stored. Most transactions the time-pressed county clerks conduct involve current documents, and they may be unfamiliar with older records. But they may be able to recommend a researcher from a local historical society who is familiar with their holdings. Almost every community has such an expert, even if not in an official role.

2. Study the place.

The next phase of your initial research is to study everything you can find on the place you’re researching. This means county histories, research guides and inventories of old records created in the 1930s by the Works Progress Administration. A good place to start your search for county histories is A Bibliography of American County Histories by P. William Filby (New England Historic Genealogical Society), a comprehensive list of 5,000 county histories. Pay attention to the footnotes in local histories, which will tell you the sources the author used; a rich resource to broaden your research. You’ll also find great sources by searching online for the county website, which might list bibliographies, source material and inventories.

My research into the Yocum family led to one of the worst burned counties I ever encountered: Taney County, Mo. The county has experienced at least three fires, and has no early newspapers or church records. I call it the graveyard of Missouri genealogy. My research on the area led me to an article about an Indian trader, “William Gillis and the Delaware Migration,” by Lynn Morrow, published in the Missouri Historical Review. (Journals by historical and genealogical societies are often overlooked sources.) Why would I read an article whose title mentions neither Taney County nor the Yocum family? Because you must read everything you can find on the burned area.

I’d learned that John Campbell, the local Indian agent, ordered two lawbreakers, a Mr. Denton and a Solomon Yocum, off Delaware land in July 1825. Yocum had erected a distillery within the Delaware line, making peach brandy and selling it to the Indians. This was in the area of my interest, 12 years before Taney County was formed.

The author’s footnote referred to a letter John Campbell wrote to Richard Graham, part of the Richard Graham manuscript collection at the Missouri Historical Society in St. Louis. This led me to a marvelous source for the early white settlers of Taney County and new potential sources, such as Indian depredations. Always read the footnotes.

3. Focus your search.

When you learn that records you wanted to search aren’t available, you must carefully consider your needs and target your search. Answering these questions will help you determine your next step:

- When did your family live in that county? Narrow the time frame as much as possible. Did another part of the family leave at a different time than your particular branch? Could that branch have left records in another county that might relate to your family?

- What county boundaries changed? Genealogical research often involves areas with disputed land claims, states being formed from territories, or state and county boundary changes. The records you need might exist in the original county, where they weren’t affected by a fire in the other county, or vice versa. For example, Kentucky was once Fincastle County, Va. Surviving Fincastle County records are with the records of Montgomery County, Va.

- Are you sure the record you need was in the building that burned? A county might’ve once stored tax records, for example, in a bank vault, even though they’re in the courthouse now. Records might’ve been sent elsewhere if storage was a problem, and thus would’ve escaped a courthouse fire. The Vernon County, Mo., courthouse burned in 1863 during the Civil War. A Civil War widow needing evidence of her marriage for a pension application heard the marriage records weren’t available. But from the county history, we learn that Confederate officials moved the records around until they fell into the hands of a Union regiment. The records were eventually restored to the county missing only one deed book (book B, if you have Vernon County family) and a few loose papers.

- Which court had authority over the matter? The legal jurisdiction at the time could affect where the records were kept. For instance, in South Carolina, equity courts had different jurisdictions from counties. It’s possible that courthouse records completely burned while equity cases survived. That’s exactly the case for Lexington District, SC; where the equity is all that survived. Copies of burned documents may have been stored elsewhere. For example, tax records for many burned counties in Kentucky are held at the state level and have been microfilmed.

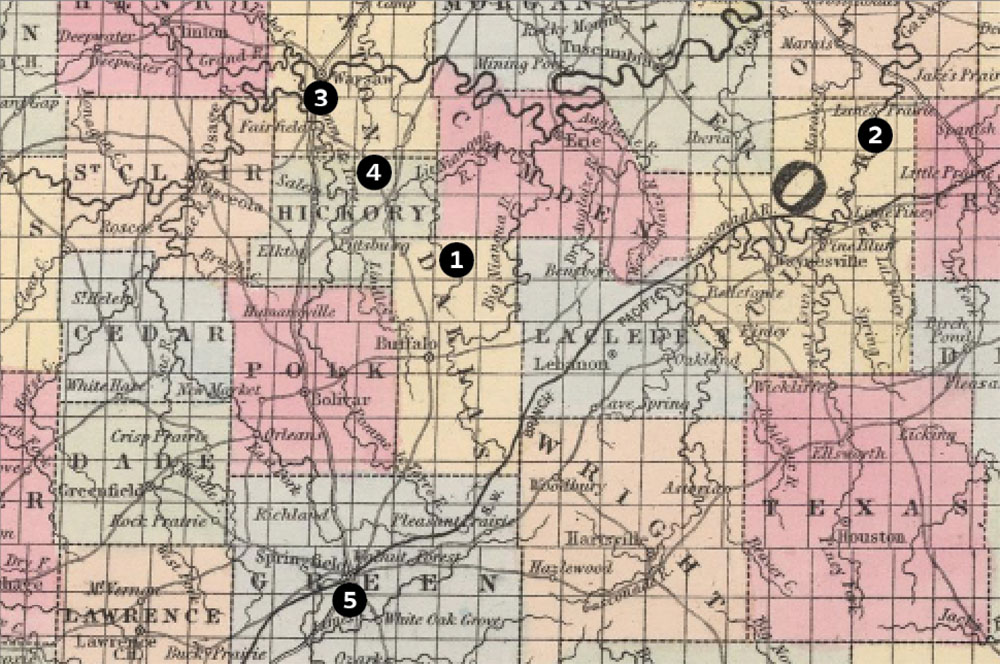

- Did your family live near a county boundary? People often took out marriage licenses in the most convenient courthouse, not necessarily in the county of legal residence. The map above shows how one couple crossed county boundaries to marry. In early times with ill-defined boundaries, people may have thought they lived in one county when they actually lived in another. The land of one of my ancestors now quite clearly lies in Laurens County, SC, but he believed the land part of Newberry, so he recorded deeds there, as did several subsequent individuals.

- What specific records did you expect to search, and why? If you own a family Bible in which a couple recorded all their children’s births, and the federal census confirms this information, you might have what you need. Learning all you can about your ancestor is important, but if your ancestor’s records were victims of a courthouse fire, you may have to accept that you’ll never know as much about this family as you’d like to.

- What information did you hope to gain? Focus on exactly what you need to know and where to obtain that piece of information. It may be that the most important thing you need to know is the link that’ll get your research out of that particular location.

- How would the information affect your line of descent? This is, after all, the critical factor.

4. Seek duplicates, substitutes and replacements.

Envision the worst possible scenario and determine how to deal with it. Let’s assume that two immense fires destroyed the record you desperately need, one 30 years after your family moved to the county, and another three days after they left. Now, you need to look for the many duplicates, replacements and substitutes that exist for courthouse records. Remember, what we need isn’t the record itself, but the information it contains.

Duplicates

A duplicate is a copy of the original record. Maybe the original was copied when a new boundary or jurisdiction was formed, or when your ancestor moved and wanted to establish a previous legal relationship. Laws sometimes required duplicates, such as for probate. A will is usually recorded in every county where the individual owned land, for example.

Copies of tax records often were sent to the state auditor, so they may be one of the few types of records to survive a courthouse fire. They can give clues to descent (by following the land transactions), migrations (when people dropped off the tax rolls or were first assessed), and ages (men usually began paying taxes at a legally defined age, and often became exempt at a certain age).

Copies of marriage records may exist in the home and church, as well as in the courthouse. Or your ancestor may have created the duplicate when submitting a document as evidence for some other purpose, such as a pension or land warrant.

Records can be filed in the strangest of places. I found a will for Jonathan Hopkins in the Revolutionary War pension application of Elijah Curtis of Massachusetts. I haven’t the foggiest idea what it was doing there. It isn’t unusual to find Bible records in Revolutionary War pension applications, or marriage licenses and death certificates in Civil War pension records.

Published records (provided they’re complete transcripts) are examples of duplicates. These records were reproduced in their entirety. Microfilmed records also would fall in this category. A courthouse may have lost records after microfilming.

Substitutes

A substitute contains exactly the same or similar information as the record you’re searching for, but it was produced for another reason. Examples of substitutes include pension affidavits, newspapers, church records, court cases, land plats and tax records.

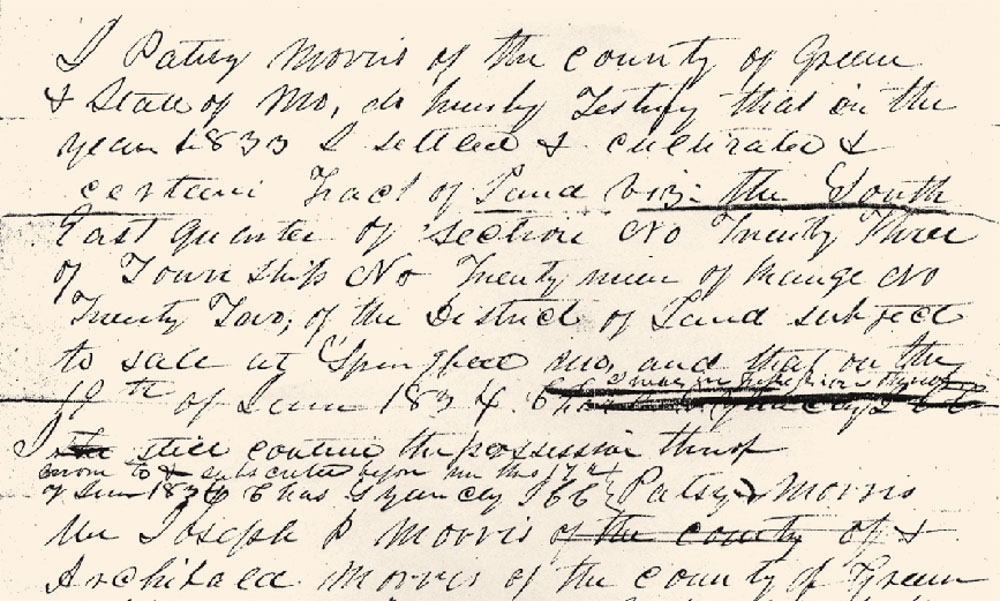

Federal pension records may include witnesses’ affidavits of a marriage. Pulaski County, Mo., lost most of its records from before the late 19th century, but I found documentation for a marriage that took place there in a pension application: Rachel Jones, widowed during the War of 1812, reported that she’d married William McLaughlin in Pulaski County, Mo., on Sept. 21, 1850, and that he died Dec. 21 the same year. You can also find reports of marriages in Oregon Donation Land applications. Isaac Cook reported in application No. 388 that he’d married his wife, Sarah, on Sept. 8, 1815, in Burke, NC.

Replacements

A replacement is a record created to replace a lost one. Examples include deeds or wills that residents re-filed after a courthouse fire, affidavits attesting to the lost facts, and the “chaining” of a destroyed title by a land title company (tracing the title from the original owner of the land to the current owner). The Hamilton County, Ohio, courthouse burned in March 1884 during a riot that ensued after a high-profile criminal trial. The county commission decided to reconstruct marriage records by asking citizens to bring in original documents for copying.

Deeds are the records most often replaced after courthouse fires, because landowners want to have a clear title to their land. William Turner filed a deed in the burned county of Taney, Mo., on July 21, 1886, asserting that 25 years earlier he’d purchased the southwest quarter of section 18, township 26, range 16.

Re-filing can occur long after the fire. Jeremiah Cheek left a will in Bedford County, Tenn., in 1823. When his heirs quarreled in 1834, they brought a suit in chancery court. The clerk recorded the will in court minutes of the proceeding. The will filed in 1823 didn’t survive a Civil War-era courthouse fire, but those 1834 minutes did.

5. Work around gaps in probate records.

When trying to establish parent and sibling relationships from before cities and states began recording births and deaths, try probate records.

Did your ancestor own property in a different county from the one where he died? By law, the land couldn’t be sold until a copy of the will or estate administration was filed in the county where the land was located. This explains why I’ve found probate proceedings and wills of Kentucky residents among the land records of Greene County, Mo. Check the records of any county where your ancestor may have bought land with plans to settle to see if his probate was recorded there. Conversely, after a person moved, he might still own land in the former county, and thus have a will on record there. Andrew Estes’ will was recorded in 1869 in Crawford County, Ark., but a courthouse fire in 1877 destroyed all probate records there. Fortunately, the will also was recorded in Miller County, Mo.

If you’re seeking a man who had means, or who married a woman whose family might’ve left her land, search records of surrounding counties. This is particularly true if your ancestor lived on the frontier and a new area opened up nearby. He may have purchased land cheaply with no intention of living there, but hoping to make money from it.

Another way to get at names from your ancestor’s burned will: Look for the wills of relatives who lived elsewhere. The estate records of unmarried people or those without children are especially good at naming relatives. Burditt Sams, age 75, died in 1846 in St. Clair County, Mo., leaving no children. The courthouse in St. Clair burned during the Civil War, destroying probate and marriage records. But the circuit court minute book survived. Recorded in those minutes is the division of Burditt’s estate among 21 heirs, most of whom didn’t live in St. Clair County, and some not even in Missouri.

For landowners who left no will, look for a land partition among the heirs. Legal notices in local newspapers often record these partitions and other circuit court proceedings. For instance, the June 5, 1858, Springfield Mirror contained a legal notice from the adjoining county of Webster, Mo., naming heirs of Jacob Lakey including 11 children, 3 of their spouses and a remarried widow.

Although you won’t find legal notices for every probate lost to fire, you’d be surprised at the number published naming at least the administrator, and sometimes heirs. They usually were issued within a couple of weeks of the death, and provide the date that letters of administration or testamentary were issued. From legal notices that appeared in the newspapers of Greene County, Mo., I was able to document more than 75 deaths that occurred in surrounding counties between 1844 and 1850, even though the original probate records had burned.

Heirs might appeal a probate court decision in an appellate or supreme court. Check libraries for a state’s decennial digest indexes, which publish appeals to state and federal courts. In my own family, the supreme court of Vermont heard “Moses Robinson, Aaron Robinson, Samuel Robinson, Elijah Robinson, and Fay Robinson, John S. Robinson, only son and heir of Nathan Robinson, deceased, heirs of Moses Robinson, late of Bennington deceased, appellants from a decree of the judge of probate for a distribution of the estate of said deceased.”

6. Find substitutes for lost marriage records.

Marriage records are often your best source for a woman’s maiden name. When they’re missing, look to these substitute sources:

Home sources

Most of us consider marriages to be important family events, so records frequently remain in the family. Our ancestors noted weddings in diaries and Bibles. They were often among the first news communicated in letters to faraway relatives.

One of my luckiest, most unusual finds involves a Kansas family Bible submitted to the Kansas State Historical Society. A loose paper that didn’t appear to pertain to the family had been inexplicably stuck into the book. It said: “Francis Berry and Esther Day were married January 29, 1812, by Tidence Lane, J.P. in East Tennessee.” The archivists at the Kansas society sent it to the Tennessee Genealogical Society, which published the details in a newsletter. The county where Tidence Lane worked isn’t a burned county, but it turns out the Berry-Day marriage isn’t recorded there.

Divorce records

Divorces were more common than you might think, and they could be heard in various courts. Records usually specify the marriage date and place. Early in US history, a state’s house or senate journals (not county courthouses) recorded divorces. You might find a divorce petition even if the divorce was never granted.

Newspapers also may carry divorce-related notices and an estranged spouse’s public warning not to do business with the other. The Jan. 7, 1845, Springfield Advertiser, for example, posted this notice: “Stephen D. Sutton vs. Susannah Sutton. Married in 1831 in Jackson, County, Alabama. Defendant deserted plaintiff in 1833 and is a nonresident of the State of Missouri.”

Church records

Marriage registers can substitute for county marriage records, and baptismal and death registers can provide details when vital records are absent. Although church records can be hard to locate, they may be available from a religious archive or a central office, and sometimes on microfilm at local libraries. For instance, Baptist church records for Middletown, Orange County, NY, are at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Ky. Examine church newspapers, as well as the records of church historical societies and church-supported colleges and universities. Find more guidance in our Church Records Workbook download.

Land records

It wasn’t uncommon for a father to make a deed of gift to his newlywed daughter, leaving clues a marriage occurred. If the family owned slaves, he may have deeded her an enslaved person. Or the bride’s father might sell her share to the son-in-law for a very low sum. If the father wasn’t fond of the new husband, he may have made his daughter a deed of gift to be held in trust, not subject to her husband’s controls.

A deed in Cooper County, Mo., illustrates this: “On July 9, 1836, Benjamin Porter of Robertson County, Tenn., for love and affection for daughter Mary Thompson, wife of Thomas G. Thompson, now resident of Cooper County, Mo., gave to her and the legal heirs of her body a negro woman slave Philes, about 18 years of age, and her boy child, Henry, aged about 7 months. These slaves are not to be subject in any way to pay her husband’s debts.” This marriage is recorded neither in Missouri nor Tennessee.

If you enjoy the challenge of a genealogy search, know that searching is almost as rewarding as finding. Solving longstanding lineage problems takes careful study of lesser known, new-to-you sources. In discussing missing records, I offer not only suggestions, but hope. In fact, I’ll wager that you can’t find a county where all the records were destroyed. Not just court records—but all the records. Some records, somewhere, still exist for that county. Finding them is up to you.

The late Marsha Hoffman Rising guided a generation of genealogists with the first edition of The Family Tree Problem Solver in 2005. This excerpt is from the newest edition of the book, which debuts in March 2019. Learn more about what’s new in this third edition.

A version of this article appeared in the January/February 2019 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for site to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com and affiliated websites.

ADVERTISEMENT