Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

“A fiddler on the roof,” he says. “Sounds crazy, no? But here in our little village of Anatevka, you might say every one of us is a fiddler on the roof, trying to scratch out a pleasant, simple tune without breaking our necks … And how do we keep our balance? That I can tell you in one word: Tradition!”

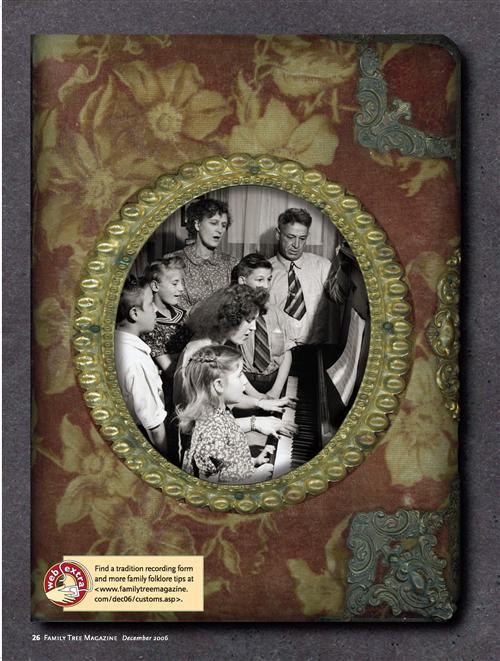

With that, Tevye breaks into a rousing chorus: “Because of our traditions, every one of us knows who he is.” He puts into words what we all know deep down — ritual and tradition are key elements of human life. They connect us by giving us shared actions and a sense of belonging to a family or place. In A Celebration of American Family Folklore (Yellow Moon Press), Steven J. Zeitlin notes that families revolve around the common ground of traditions. Storytelling, he says, represents “a heightened form of communication which holds the family together and acts, in one person’s words, as a kind of glue.”

You don’t have to break into song to recognize tradition in your own family. But our tips for finding out where folklore fits in your family tree may just strike a chord — and make your genealogical research sing.

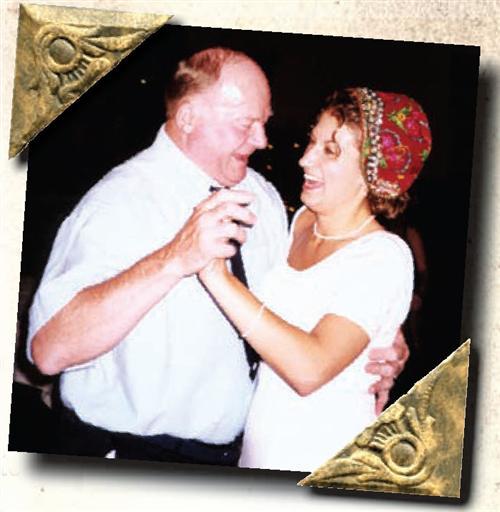

Same old song & dance

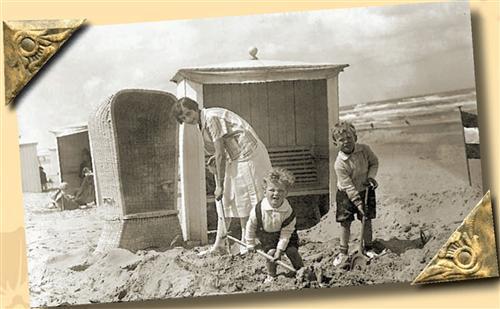

Most family history is really just remembering. Like Tevye’s daughter, who leaves her hometown to be with her betrothed, our immigrant ancestors experienced separation from their families. They kept their ties to the old country by following the same traditions as the folks back home. Even today, traditions provide comfort amid the rapid pace of life.

We genealogists want to know more than the bare facts about our ancestors — we want to know the stories of their lives. We look to cultural and religious traditions, family stories, and customs our forebears initiated to evoke our roots and link us to the past in a tangible way. Traditions passed through generations keep our ancestors’ legacies alive. They come in several types, including:

* Celebrations: These traditions are built around special occasions. Your clan might sing a special birthday song or always decorate the Christmas tree the day after Thanksgiving.

* Heirlooms: Most families have treasured items connected to certain people or memories. My mother had a can for the powdered sugar she used to decorate cakes and cookies, and the can had to come along to family gatherings so the goodies would look perfect once on their platters. One time, while we were driving from Pittsburgh to Cleveland for a cousin’s bridal shower, Mom realized she’d left the can behind and cajoled my father to turn around. Now the can is in my kitchen cupboard.

* Rituals: Every family creates its own practices or continues those of previous generations. When I had the mumps as an 8- or 9-year-old, my grandmother and mother wrapped sauerkraut in a cloth I wore around my neck to reduce the swelling. I think it worked, but it was awful, and the smell of sauerkraut always stirs the memory. (Imagine — a Slovak who can’t eat sauerkraut!)

* Folklore: This is the stories you tell your kids. My father liked to recount how as a young boy, he used to swim with friends in the Monongahela River near his Duquesne, Pa., home. His disapproving dad would say to him, “Were you swimming in the river?” “No, Pap,” my dad would sheepishly respond, his blond hair covered in a telltale green film. Then my grandfather would look him in the eye and say, “Next time, if you drown, don’t come home.” My grandfather died before I was born, and this story gives me insight into his personality — something I can’t get from documents and pictures.

Finding the notes

You don’t have to look far to find the traditions in your family. If you haven’t yet completed that first genealogical step of combing your attic, basement and closets for home sources — photo albums, letters, diaries and documents — do that now. Look for mentions of regular activities, family stories and heirlooms. Then start recording all the family traditions you uncover using the form at <www.familytreemagazine.com/forms/people/traditions. pdf>. Be sure to note what the tradition is, when it started and who started it, which family members participated, how you learned about it and how it’s carried out (for example, does it involve certain clothing, religious rituals or special food?). Record whether the tradition is associated with a particular ethnicity and describe old photos or letters you have that document the custom.

Your best sources of family folklore are older relatives. So set up a time and place to talk to Aunt Betty — perhaps she can tell you why pecan pie is always served on Thanksgiving and plum pudding on Christmas. Or maybe she can explain how the annual Fourth of July fishing trip came to be. Ask older relatives about special stories or traditions from their childhoods, and whether they’re aware if any have been embellished. For more interviewing advice, see <www.familytreemagazine.com/articles/memoirs2.html> and the September 2004 Trace Your Family History, a special issue of Family Tree Magazine.

If you need a conversation starter or icebreaker, try the prompts in a set of Go Ask Anyone cards <www.goaskanyone.com>. Arrange to audio- or videotape your interviews, and inquire about photos, documents and heirlooms that go along with the stories. Those might be family Bibles; recipes; holiday cards and decorations; bridal, baby and funeral books; photographs; and heirlooms such as china and jewelry. Bring your scanner to make copies, since this evidence will give credibility to the folklore you uncover.

Your ears should perk up if you learn someone has “broken” the tradition or deviated from the norm, such as marrying outside his religious or ethnic background. Make sure you ask why. Did that generation move in circles outside their Italian or Polish “cluster” community? Maybe cousin Ed met his spouse while serving on the Western Front during World War II. How did the older generation feel about the deviation from tradition? These questions may lead you to additional clues about the evolution of your family.

Concerted efforts

“How we met” family stories are usually compelling and engaging. I was fascinated by the tales of how both sets of my Slovak grandparents were introduced by “matchmakers” when they arrived in the United States. My grandmother’s sister, who owned a boardinghouse where young male Slovak immigrants (including my grandfather) stayed, matched my paternal grandparents. My maternal grandmother’s brother-in-law worked in a coal mine with my grandfather, and knew he was looking for a bride. Through research, I was able to verify the stories surrounding these arranged marriages. I found it especially interesting how this Eastern European custom traveled to early-20th century America. But by the next generation, the practice of matchmaking had disappeared from both sides of my family.

Researching the origins of such traditions will add to your family lore and could point you to an ancestral homeland. Start by reading local histories, such as Growing Up Greek in St. Louis by Aphrodite Matsakis (Arcadia Publishing). Search online library catalogs for books on folklore, peruse the society pages of your ancestors’ local newspaper, and explore Web sites of ethnic genealogical societies (use Cyndi’s List <cyndislist.com/society.htm> to identify thesegroups). People love reminiscing, so don’t be shy about posting questions such as “Ever heard of a bride carrying a lump of sugar down the aisle?” to online message boards. Find tradition-focused mailing lists ¦ at <rootsweb.com/~jfuller/gen_ mail_famhist.html>.

For help investigating the sources of favorite family foods, see the December 2004 Family Tree Magazine and check out the resources at <cyndislist.com/recipes.htm>. Get advice on researching your familyheirlooms in the October 2004 Family Tree Magazine. Antiques stores and history museums also are good sources of artifact information.

Ringing true

We’ve all heard family stories: How Great-great-grandpa escaped from a Russian prison during World War I and tricked a border guard into letting him pass, or how Great-aunt Sally just missed boarding the Titanic. Glorious moments in our family history may get elaborated as they’re passed down, and may even turn out to be outright lies. “Each form of family lore can convey only one portion of the family’s past,” Zeitlin says. “It skews reality in a particular way.” Such stories and customs can be genealogically useful, whether they lead to ancestral clues or provide colorful background for facts you’ve gathered. But how do you sort fact from fiction? Follow these steps:

*Take stock. Examine the story or tradition line by line. Make a list of the key names, dates, places and events involved.

* Divide. Investigate the aspects of the story that are provable — that is, they created some type of record. Become familiar with the records of the time period and place. Read Family Tree Magazine articles (the index at <www.familytreemagazine.com/ftmindex.asp> will help you find relevant ones) as well as the FamilySearch research outlines at <www.familysearch.org> (click Guides on the home page).

* Conquer. Consult the sources you’ve identified, whether census, immigration, vital and other records; obituaries; biographies; or local histories. Talk to family members, too. If what you find contradicts family legend, record both: “Aunt Mary says Great-grandma nursed soldiers alongside Florence Nightingale during the Crimean War, but church records show she was in Cornwall at the time.” Include citations and copies of documents.

Not every tradition or piece of folklore will result in tangible records, but evaluating each one might lead you to a new detail. That’s what happened to me — flip to the previous page for an example of how I investigated a family narrative.

Orchestrating customs

What if you don’t uncover any family customs? Traditions don’t have to be old to have meaning, so start your own. Visit museums and restaurants specializing in your homeland. Check newspapers for church picnics, folk festivals and holiday observances. Join an ethnic heritage society (see <cyndislist.com/soc-gen.htrn> or do a Google <google.com> search).

Is your family African-American? Participate in Kwanzaa. Got German roots? Find a nearby Oktoberfest.

For more options, see Family Traditions: Celebrations for Holidays and Everyday by Elizabeth Berg (Reader’s Digest Association, out of print).

You don’t have to limit yourself to customs of your ethnic background. My Irish and English husband honors a Scottish New Year’s Eve tradition called “first-footing.” To ensure good luck all year, the first person to enter the house after midnight should be male and dark (a possible throwback to Viking days, when blond strangers on your doorstep meant trouble), and bring coal, shortbread, salt, a black bun and whiskey.

No swan song

Don’t let the traditions you’ve inherited and created end with you. Here are some ways you can leave a legacy for future generations:

* Make rituals part of daily life. Try setting aside a weekly meal to say a special prayer or make an ethnic food. Find more ideas in Everyday Traditions: Simple Family Rituals for Connection and Comfort by Nava Atlas (Amberwood Press).

*Create a calendar. Note family holidays, birthdays and anniversaries — tell your grandchildren what these special days mean.

*Make a family tradition scrap-book.The Complete Guide to Creating Heritage Scrapbooks (Memory Makers Books) and Scrapbook Storytelling by Joanna Campbell Slan (EFG) explain how.

*Play family history board games. Use them to teach your kids or grandkids about family history. Two of my favorites are Family Lore <www.familyloregame.com> and LifeStories <www.boardgames.com/lifestories.html>.

*Plan a family reunion (if your family doesn’t already hold one).

Include storytime and other activities to get the generations together. See the May 2006 Trace Your Family History, a special issue of Family Tree Magazine, for help.

At the end of Fiddler on the Roof, the constable gives Tevye and his neighbors three days to pack up and leave their beloved Anatevka. After the initial shock, the villagers rationalize that Anatevka is, after all, just a place. They sing, “Soon I’ll be a stranger in a strange new place, searching for an old familiar face.” Our forebears may have left their homelands, but their traditions would remain with them — and now, with us. In keeping sight of “Tradition!” you’ll always carry the tunes of your ancestors.

Facing the Music

Uncovering the truth can be difficult when family stories have passed down for generations. Here’s how I analyzed a narrative my father’s sister, a Roman Catholic nun named Sister Camilla Alzo, wrote in the 1970s. She’d heard the story from her first cousin Mary Hatala and recorded the prose as Mary told it to her:

Ilia (Helen), our grandmother, married Michael Finch, a bootmaker, in Liverpool, England. Mr. Finch was a widower with two children: John Fenchak and Anna Ragan, now both deceased.

Mrs. Mary Ceyba was born to them in Liverpool, England. Then they came to Freeland, Pa., near Scranton, where Anna Bavolar was born. Then they returned to Europe and Elizabeth (my mother) and Mike (an uncle who was in Argentina) were born in Czechoslovakia, in Poša.

When Dzedo [Grandfather] died, Cetka [Aunt] Mary Ceyba came to America and was hired out for room and board and one change of clothes per year.

Mr. Fenchak (John) came to America and had Anna and John Fenchak Anna Ragan married in Europe and stayed there. Her two sons, Mike and John, came to America. Cetka Ceyba sent for Elizabeth (my mother) to come to America. She came, had a job working for a Jewish family but visited Cetka Ceyba often. Dad came over to America and was a boarder at Ceyba’s. This is where Mom and Dad met and then married.

Cetka Bavolar was matched for marriage by Cetka Ceyba. Cetka Bavolar went to Europe with Mary because Grandma was sick. Cetka stayed because World War I broke out and they wouldn’t return to America. Grandma died during the war. Her second husband was Zelenak, who was a very possessive person. He didn’t want Cetka Bavolar to come in and take care of Grandma. He had three sons by his first wife and he married Grandma to have a wife to care for his boys.

I was confused: How did my great-grandmother, who was living in Hungary, meet and marry a man from Liverpool? Not to mention all the surnames and places. But this secondhand account gave me a place to start. First, I wrote down the key details from the narrative:

* Surnames: Bavolar, Ceyba, Fenchak, Hudak, Ragan, Zelenak

* Places: Argentina; Freeland, Pa.; Liverpool, England; Poša, Slovakia

* Events: deaths, immigration, World War I

Using passenger lists, I traced Michael Finch’s travels from Poša to Freeland and back to Poša, as well as the later immigration of his children. US census records told me where the children settled in Pennsylvania, and vital records both here and abroad verified births, marriages and deaths. Microfilmed church records from the Family History Library confirmed his widower status; census records showed he was a bootmaker.

We do all kinds of strange things for no better reason than that’s how it’s always been done. But how did those customs get started? We uncovered the origins of five modern-day traditions.

* April Fool’s Day: References to this holiday, originally called All Fool’s Day, first appear in Europe during the late Middle Ages. Its predecessors include the Festus Fatuorum (Feast of Fools), which evolved out of the Roman winter festival Saturnalia.

* The wave: No one knows who started the first wave at a sporting event (or how that guy got everyone to join in). The human undulation became popular during the 1986 World Cup in Mexico — broadcasters called it the Mexican Wave, or La Ola.

* Key to the city: Today’s custom of honoring a distinguished citizen with a key to the city hearkens to the medieval era, when feudal lords protected towns behind walls and gates. An important diplomat got a key so he could enter whenever he wanted.

* Throwing salt over your shoulder

Back in Biblical times, salt was an expensive commodity. Spilling it was bad. But if you tossed a bit over your left shoulder (where Satan presumably stands), you’d blind the devil to your faux pas.

* Cans on the getaway car:

Historically, people have used bells and other noisemakers to scare away evil spirits that might be lurking around. Dangling cans behind newlyweds’ carriage kept demons from following them into married life.

ADVERTISEMENT