Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Zulma Ramos died alone of cancer two weeks after the start of 2016. Investigators at the Orange County, Calif., coroners office, charged with notifying her family, knew that she was somebody’s someone. A sibling? Mother? Wife? Friend? Who would want to know she was gone?

Her case is not an unusual one

Every year, US county offices investigate thousands of unclaimed deceased persons, looking for next of kin to contact about burial arrangements and estate distribution—and just to let the family know what happened. But finding families isn’t always a simple matter. Overburdened coroners and medical examiners increasingly are reaching out to another group accustomed to reconstructing the lives of the dead: genealogists.

After 71 days of working leads in Ramos’ case, Supervising Deputy Coroner Kelly Keyes contacted the Genealogical Society of North Orange County (GSNOCC) in Yorba Linda, Calif. Follow the three amateur genealogists—myself, Maury Jacques and Lynn V. Baden—who worked the case, using scraps of minimal and misleading information to find Ramos’ lost family.

Separate ways

Ramos was discovered dead in her Garden Grove, Calif., apartment after a neighbor who hadn’t seen her in a few days got worried and called 911. The coroner concluded Ramos had died Jan. 14. Papers in the apartment showed she was being treated for breast cancer.

Like all of us, Ramos started her life with a family. Many whose lives end alone lost those family ties due to geographic distance, poverty, drug addiction or childhood trauma. The National Institute of Justice estimates that 40,000 sets of human remains lie unidentified in county morgues across the country. The National Missing and Unidentified Persons System database of unclaimed remains has around 12,000 open cases.

Finding volunteers

County administrators’ offices launch kinship searches to notify relatives of the death and locate heirs to a person’s estate. But in many counties, administrators don’t have the resources for extensive investigation. That’s where volunteers come in. An online group called Unclaimed Persons, which serves as a clearinghouse for county officials and volunteer researchers, has solved 482 cases, a 70 percent solve rate. In Orange County, the coroner and GSNOCC began partnering on cases in January 2016. So far, the group has solved all but two cases of the 70 worked. Some take 15 minutes. Others, hundreds of hours.

Volunteers aren’t necessarily certified or professional genealogists, but they do have research experience and the need-to-know persistence of a private detective—along with a desire to help. “Bringing the deceased and the next of kin together is a loving and caring act for the family involved and for the larger community,” says Baden, a librarian and genealogy veteran of 30 years.

Jacques, a genealogist for eight years, saw the opportunity to stretch his skills while doing good. “This was a new and fun challenge that I knew I could do. I wanted to help.”

Case at hand

Genealogy is central to kin research. Volunteers look for the names of the deceased’s parents, grandparents and even great-grandparents, then work forward to identify descendants of all those ancestors. The cases involve problems familiar to genealogists: common surnames, no surnames, multiple names, variant spellings and false history.

Clues in Ramos’ apartment had helped Keyes locate an ex-husband, who provided names for her parents: Rita Rivera Feliciano and Arturo Ramos Lombard. But Ramos’ marriage had been brief and distant, and her ex could offer little else except that she was born in 1945 in Puerto Rico, and may have had half-siblings.

Starting the search

We started by trying to confirm this vague information. Based on Zulma Ramos’ reported age at death, 71, finding living parents would be a long shot. Siblings, children or cousins were more likely. Still, this seemed like a lot of leads compared to other unclaimed persons cases we’ve worked.

Scouring public record websites, such as BeenVerified, Instant Checkmate and Intelius, is among the first steps in kin searching. The array of online information available about living people can be shocking. Beyond addresses and phone numbers, these sites offer details from property and financial records, professional licenses, interactions with law enforcement, and vehicle information. Websites with databases of these records cost around $25 to $58 per month to use, with some sites allowing a smaller fee per search.

Using the databases

Type a name into a people search site, and two types of associates of the person typically emerge: close family and possible relatives. The latter may include neighbors, roommates, business partners and in-laws. Kin researchers keep notes on associates and compare their listed addresses across records, looking for overlap with our unclaimed person. But the results were dead ends in Ramos’ case.

The next step was identifying historical records to search for. Ramos had been married and divorced, both record-creating events. She lived somewhere; that meant telephone directories and other residential records. If she indeed was born in Puerto Rico, there should be birth and perhaps church records. Assuming her parents were deceased, their death certificates and burial records would be a source.

We searched familiar genealogy websites including Ancestry.com and FamilySearch, and created an online tree for Ramos. We used family group sheets to document sources and made notes of negative findings. But with such a common name, unless we had something to connect a piece of information to, it couldn’t be considered a fact. In the end, all that researchers could associate directly with Zulma Ramos was a 1962 record of arrival by plane in San Juan, PR, her Nevada marriage record, and three residential addresses from Garden Grove, Calif. Huge chunks of her timeline were missing.

Family finds

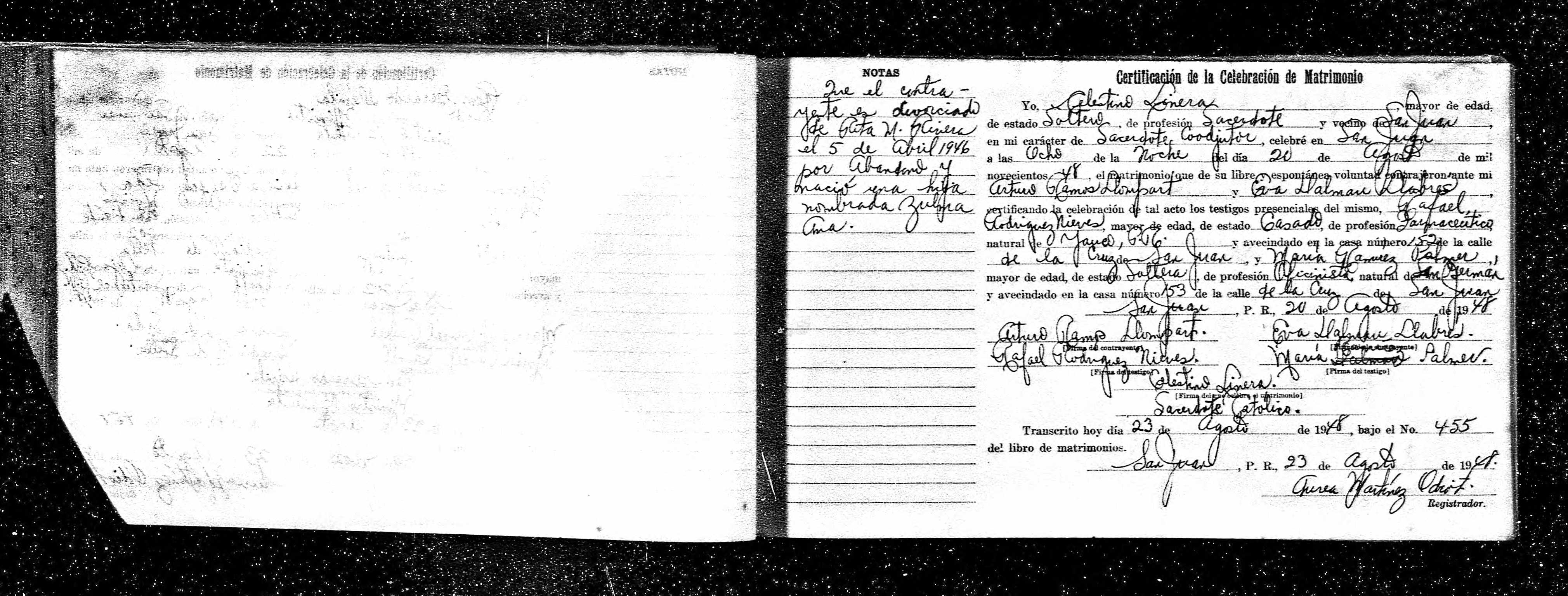

Another common genealogical problem cropped up in this search: the language barrier. Some Puerto Rican records are written in conversational longhand Spanish, rather than in neat columns or on a preprinted form. Fortunately, Google Translate was enough to get by and understand documents such as the marriage record for Ramos’ parents, dated Feb. 4, 1944, in San Juan.

We never found a death record for Ramos’ mother. But we soon learned that her father’s second surname wasn’t Lombard—it was Llompart. In Spanish-speaking cultures, children traditionally receive two surnames: the father’s (considered the primary surname), followed by the mother’s. Ramos is the surname that Arturo took from his father; Llompart is from his mother (which she, in turn, received from her father).

Spelling makes all the difference

With that spelling, we found Arturo Ramos in the 1930 and 1940 censuses of Santurce, PR, with a brother, Ernesto. Arturo was born about 1921; Ernesto, in 1923. Death records showed both brothers died in 1989, Ernesto in Florida and Arturo in San Juan. Their parents—Zulma Ramos’ grandparents—appear in the 1910 and 1920 censuses.

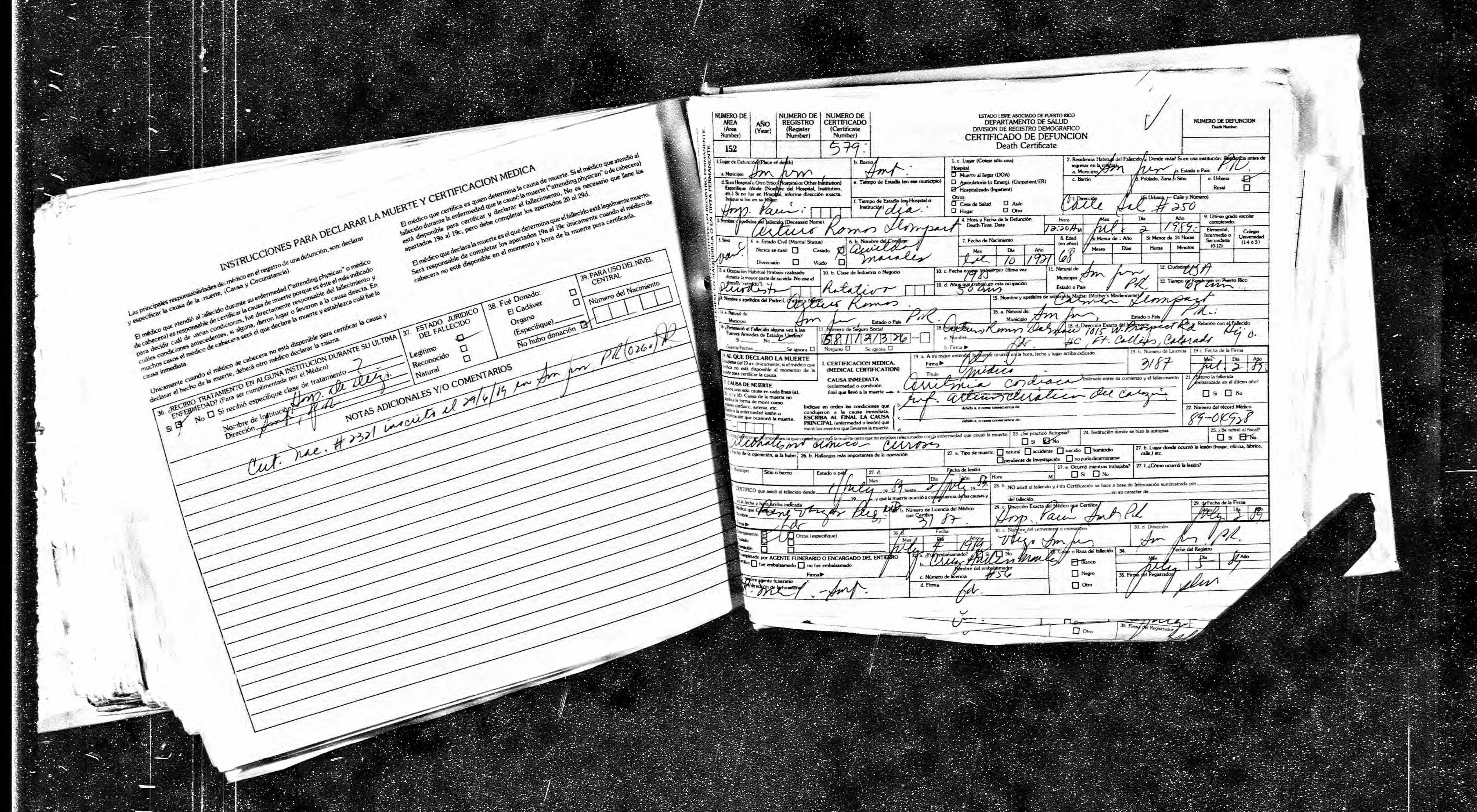

A record of Arturo Ramos’ second marriage, on Aug. 20, 1948, to Eva Darmau, had particularly helpful notas: Arturo and Rita had been divorced in April, 1946, because he’d abandoned Rita and his daughter Zulma Ana, then a year old. But his death record led to a break in the case: It listed an hijo (son), Arturo Ramos Dalmau, living in Colorado, as his next of kin. The son’s second surname was almost identical to that of Arturo’s second wife. Could this be a half-brother to Zulma Ramos?

Public record websites gave up nothing on the son. Nada, as they say in Puerto Rico. Arturo Ramos’ death certificate listed alcoholism as a contributing cause to his passing. Maybe he’d been estranged from his children. Following that hunch, we searched with the son’s maternal surname, Dalmau. And there he was, in Fort Collins, Colo. He showed up on four living person sites, with address and phone number listings matching his location and estimated age.

Making contact

Volunteers aren’t permitted to contact potential relatives of a deceased individual. When they identify a living person believed to be family, they hand the case back over to the coroner’s office. Then they wait, holding their breaths, to find out if the search was successful.

Keyes called the man we’d identified as Zulma Ramos’s half brother—and it was him. Arturo Ramos Dalmau, though sad to hear the news, was relieved. “I visited her 24 years ago for a week, and it was wonderful,” he says. “I never thought it would be the last time. After that, I would call her every week or two, but gradually, she just stopped returning my calls. I don’t know why.”

When they last spoke, she told him she’d been diagnosed with breast cancer. She said she felt good after being prescribed antidepressants for the first time in her life. “She was still my same driven, independent sister, with her ribald sense of humor,” Dalmau adds.

Putting the pieces together

He filled in more puzzle pieces. Zulma Ramos, fiercely independent, moved alone to the mainland at age 17, finished school and worked at a hospital. She lived in Texas for a while, a residence that didn’t show up in any of our searches. Her mother also had moved to Texas, where she remarried and later died with her husband’s last name. That’s why we couldn’t find her death certificate.

Arturo Ramos had another daughter with a third woman, whom he never married. This daughter, still living, took the surname of her mother. That left not a shred of evidence connecting Zulma Ramos with her half-sister. Dalmau disputes the nota indicating their father

abandoned his eldest child. Father and daughter kept in touch by phone, and he helped her financially. “The first time I ever saw Zulma cry was when our father died in 1989,” Dalmau says. “She was visibly the most upset of all of us.”

A sense of closure

“I hear comments from a family like ‘we had hired a private investigator to track him down with no luck,’” Keyes says, “or, ‘we always wondered what happened to her,’ or that ‘mom died wondering where he was, and now we’ll be able to bury his ashes next to hers.’”

Now, Dalmau no longer has to wonder and worry about his sister. Search volunteers hope to bring this peace to families, although not all contacted family claim their dead. Sometimes the chasm is too deep. I always hope that once the shock of that phone call dims, the news of the death still brings some kind of closure.

ADVERTISEMENT