Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Introvert, extrovert, ambivert, Type A, Type B, sanguine, choleric, melancholic, phlegmatic, artisan, guardian, idealist, rational (to name a few): The list of personality types defined over the centuries resembles a psychological potluck. From Plato to Dr. Phil, personality theorists and hypotheses stack up like plates at a family reunion. Books about the latest philosophies line self-help shelves in bookstores. Some folks fork over $125 per hour for sessions on a therapist’s couch.

Amid this fascination with sorting out our own personalities, genealogists may yearn to find out what made their ancestors tick. Were they reserved or outgoing? Spenders or misers? How did they treat people? What did they do for fun?

You chronicle your ancestors’ behaviors—what they did and when they did it—with the genealogical records you find. A June 23, 1868, marriage certificate states Elizabeth Brant married Barnett Engelke. That’s a handy piece of behavioral evidence. Yet the circumstances of her marriage reveal her characteristics. Newspaper accounts divulge that Elizabeth defied her parents and eloped on a Missouri River steamboat. That’s personality—independent, bold, romantic and perhaps a little reckless.

Instead of just collecting names, dates and events, consider adding an amateur psychologist’s cap to your genealogy detective gear. Here’s how seven common records can breathe personality into your family tree.

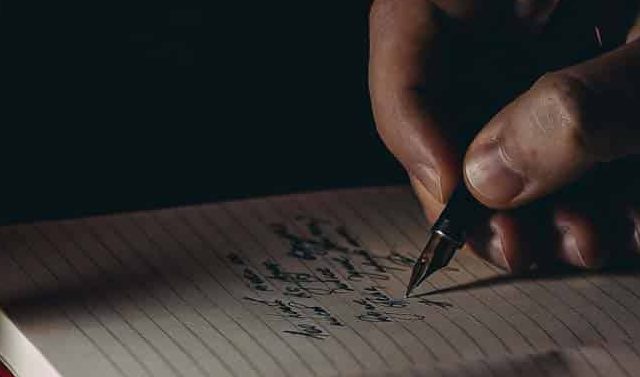

Diaries and letters

What could deliver more insight into a person than his own words? If your ancestors’ writings are tucked away somewhere, you’ve got a jump-start on creating personality profiles. Don’t just scan for names and dates—slow down and read between the lines. Think about characteristics the writer’s words reveal.

Some diaries were emotional outlets; others were logs of daily routines. But even one filled with monotonous musings about the weather can tell you something. When Great-granddad wrote “hot and windy today,” he displayed the discipline to write in his diary each day.

If Great-aunt Edna didn’t keep a diary, the journal of another family member or a friend might hold insights about her. John Osborn, an early 1800s North Carolina resident, kept careful notes in his diary about his whiskey-making business, including names of his customers. Suppose John made weekly moonshine deliveries to your ancestor—tells you something, doesn’t it? It’s up to you to draw your own conclusions.

Before the telegraph, telephone and email, letters could be newsy time capsules. Ancestors’ letters may be scarce, but again, those written by others might contain personality-revealing gossip. In an 1848 missive giving a rundown of his siblings, Wiley Hubbard says his sister Vicy is “single but it’s not her fault.” So I know she wasn’t undesirable—at least not in her brother’s eyes—but perhaps unlucky in love. William Workman’s 1843 letter accuses John Scolly of duplicity and falsehood. He tops off his quill-pen lashing by calling Scolly an “undeserving old hypocrite.” Charles Bent further fleshes out a persona in an 1841 letter commenting on Scolly’s “large share of fame” with young ladies. Add “irritating” and “skirt-chaser” to Scolly’s personality profile.

Focus your search on the diaries and letters of people who lived near your ancestor. Start with a local historical society. Search online catalogs of local, state and university libraries, and consult American Diaries: An Annotated Bibliography of Published American Diaries and Journals/Diaries Written From 1845 to 1980 by Laura Arksey (Gale).

Newspapers

The standard newspaper obituary is a flattering personality assessment: She was beloved by all, he was a kind and devoted husband, and so on. But obituaries can reveal genuine personality insights in mentions of the deceased’s accomplishments and activities. Henry O’Neill’s 1883 obit noted he’d traveled from New Mexico to Australia. Long before the days of Google Maps, Henry’s excursion across the Pacific Ocean tells me he was adventurous, resourceful and courageous.

Your ancestors might have been mentioned in news articles, too. Don’t just focus on the facts—consider what an article says about who your ancestor was. A 1914 California paper reported that fishing buddies William Davis and Harley Freeman struggled for four hours to haul in a 33-inch, 14-pound trout. Sure, maybe they were just hungry, but I think that two-sentence tidbit suggests a bundle of characteristics: stubborn, tenacious, strong and willful. (I’m referring to William and Harley, of course, but I suppose this also applies to the trout.)

Scan newspaper society pages for social comings and goings. An 1886 Kansas City newspaper reported “Dr. and Mrs. M. Munford will leave about July 1 for an extended trip through New and Old Mexico and Southern California. They will be absent until about September 1.” Besides giving the green light to newspaper-reading burglars, this notice illustrates the personalities of Dr. and Mrs. Munford. Think about the effort it took to travel for two months in the Wild West in 1886. Perhaps they had the means to go first-class, but undertaking a long western trip during a hot, dusty time of year still required an adventurous spirit and a sturdy constitution.

The internet has dramatically changed how genealogists can research historical newspapers—great news for those of us who’ve nearly gone blind scanning pages of microfilmed newspapers. Millions of digitized newspaper pages are at sites such as GenealogyBank, Ancestry.com, Newspapers.com and ProQuest Historical Newspapers (free through many libraries).

Clubs and organizations

Clubs, organizations and secret societies have been around ever since people started noticing they had things in common with other people. Your ancestors’ joining options abounded. There were occupation-related, religious, military, political, sports, ethnic and hobby clubs. Membership in fraternal organizations such as the Masons, Knights of Pythius, Elks and Odd Fellows also was common. Where and with whom your ancestors chose to spend their spare time registers high on the personality-profile meter.

The simple fact your ancestor was a club member is informative. People who join clubs tend to be sociable. The type of club gives you some insight, too. Was Great-grandma a member of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (which began advocating prohibition in 1873)? Did Great-granddad join the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), an organization for Union Civil War veterans? Consider the organization’s purpose and whether it was dedicated to charitable projects or political activism—or whether the main objective was smoking, drinking and playing cards.

Aside from mere membership, club records can reveal additional nuggets. If your ancestor served as an officer, he may have been a natural leader. Always paid his dues on time? He likely was organized. Perpetually late payments may signal forgetfulness, a miserly mindset or a struggle to make ends meet.

To see if your relative joined a club, scour obituaries and family papers for references to membership, and look for insignia in old photos and on tombstones (see Phoenix Masonry for fraternal symbols). Find clubs operating in your ancestor’s time and place by reading county and city histories, checking city directories and spotting meeting notices in old newspapers.

If the organization still exists, visit its Web site or contact headquarters to ask where old records are. GAR lodges operated independently; many records are in local and state historical societies. The Family History Library (FHL) has some records on microfilm; try running a keyword search on the organization’s name. See Cyndi’s List for links to online sources of fraternal records.

Business records

How you spend your hard-earned dollars says a lot about you, and the same applied to your ancestors. Despite nostalgic notions that our ancestors were poster children for self-sufficiency, most of them actually did venture into town occasionally for store-bought goods. Naturally, they bought food and other household staples. Look, instead, for purchases that were a little unusual or extravagant—for example, a porcelain figurine, a child’s toy or a book of travel essays. My ancestor bought three yards of lace at the general store a few days before her death. She was old, ill and poor, yet she still wanted a touch of elegance for something she (or someone else) was making.

Shopkeepers generally recorded their transactions in ledgers or account books, as did Santa Fe businessman Henry O’Neill. His 1850s general store ledger books reveal many customers bought clothing, shoes, canned goods and the occasional cup and saucer. People plunked down the most cash, however, for alcohol—some imbibers bought the hard stuff daily.

Zero in on business records created at the place and time your ancestors lived. Ledgers and account books are usually in historical manuscript collections at libraries and archives. Search online catalogs using terms such as ledger, daybook, journal, account book, retail, general store and sales. The FHL has microfilmed some business records—run a place search on the county or city name and look for a business records heading.

An ancestor’s diary also may record his expenditures. Sort through family papers, too, for receipts, account books and other financial records.

Church records

If your ancestors were churchgoers, you may be able to track them literally from cradle to grave. When examining church records, look beyond the giddy discovery of vital events such as births, marriages and deaths to peruse for personality clues.

Which religious denomination appealed to your ancestor? Did he stick with the religion of his parents and grandparents (a traditionalist), or was he attracted by a passionate preacher who established a new religious order (a non-conformist)? Think about the religion’s tenets. Many of my early American ancestors were Quakers, and studying Quaker beliefs gave me a better understanding of their personalities. A couple of my ancestors were dismissed from their Quaker meetings for taking up arms. Fighting in the Revolutionary War trumped their religion, and I can imagine the emotional conflict that must have accompanied the decision to fight. Visit the Association of Religion Data Archives for information on more than 400 denominations.

Membership rolls and attendance lists might tell how often your ancestor attended church. Newsletters and bulletins could reveal other church activities she participated in; for example, whether she taught Sunday school (fond of children) or headed up the anti-slavery committee (a leader and activist). Meeting minutes could say even more. When Presbyterian John Robertson died in 1893, the elders of his church were so affected by his sudden death that they wrote a tribute in the business meeting minutes. They praised his godly character and described his service to the church as an elder and trustee.

Church records could range from tithing lists to pastors’ journals and letters. If the church still exists, start sleuthing there. Otherwise, contact denominational offices (if they’re still around), or look in college, university, state and historical society collections. The FHL has some microfilmed church records, too: Run a place search and look for a church records heading.

School records

Even though education was a haphazard affair in early America, your ancestors might have attended a school that produced records. Yearbooks top the list of school records for detecting personalities. Think about the details they chronicle: clubs, activities, honors and achievements. Was Great-granddad a multisport athlete, president of the chess club or a drum major? Did your great-aunt win the award for friendliest or most talented? On the other hand—and equally revealing: Is your forebear’s school career marked solely by a class picture? A lack of involvement could mean she was shy, or maybe her responsibilities at home thwarted extracurriculars.

If you have old report cards, think about what those grades say of your ancestor’s interests and classroom behavior (does the teacher describe her as industrious, or say he talked out of turn?). Search for other educational records, too, such as school-board-meeting minutes: Maybe your ancestor was the subject of a disciplinary hearing or mentioned as an award recipient. Review attendance records—perfect attendance suggests the student was diligent and healthy; three absences a week suggest something else.

Look for school records at all levels of education, from elementary to college. If the school system is still in operation, call the district office. The school or a local library probably has old yearbooks; websites such as Dead Fred and Ancestry.com have digitized versions. Other school records might be in state archives, government repositories or historical society collections. Colleges usually keep their old records in their own archival collections.

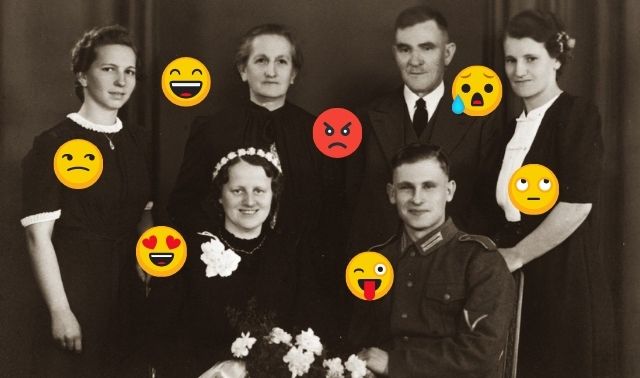

Photographs

They say a picture is worth a thousand words, and that certainly applies to fleshing out ancestral personalities. Many old photos look remarkably alike: a stern visage poised in front of a bland backdrop. Blame that on the photographic norms of the times. As photography advanced, so did opportunities for personalities to creep into snapshots.

The mere existence of a photo of your ancestor begs the question: What prompted him to put away his plow, get cleaned up and fork over cash to sit for a photo when it wasn’t a common practice? Maybe he was thinking of you and his other descendants, many years later. There’s an element of self-preservation in photographs—a desire to live forever, at least in people’s minds and photo albums.

Examine the photographic clues. Did those pictured wear the latest, most- expensive fashions, or did their clothes suggest more modest means? I’ve often wondered about a posed image of my grandfather taken when he was 19: His clothes are crumpled, ragged, dirty. He has a shaggy—but friendly looking—dog. Why didn’t Grandfather spruce up a bit? Maybe he didn’t have anything nicer, or he happened across an itinerant photographer and spontaneously decided to pose. Whatever the reason, I can tell he wasn’t a man who worried about appearances.

Look at everything in the background. My ancestors apparently had a strong affection for their modes of transportation: Horses and cars often appear in the background or front-and-center in their photographs. No big-ticket items in sight? Look at the smaller trappings: A campaign pin on the coat pocket, a locket around the neck or a two-foot-wide hat balanced on your petite grandma’s head all point toward personality.

Just like us, our forebears were complex creatures, so be careful when playing Sigmund Freud. While you ponder personality clues in records, consider the circumstances. How to interpret those weekly whiskey deliveries? Maybe Great-granddad was a drunk, or maybe that morning swig eased his gout. Spotty presence at church doesn’t have to mean your ancestor was a sinner—maybe he lived far away, or he was needed at home, or his horse was sick. So remember to couch your personality assumptions in terms such as “Based on Aunt Jane’s high school yearbook, I believe she was …” or “in this newspaper article, Great-grandpa comes across as …”

Though we’ll never actually know our long-dead ancestors, we can make them a little more real, a touch more three-dimensional. So plunk your ancestors on the therapist’s couch and use these records to peel back the layers of personality beneath the names on your genealogy charts.

Case Study: Delving into the Inner Psyche of a Successful but Troubled Lawyer

Hugh N. Smith, attorney and pivotal political player, arrived in New Mexico in 1846 with the conquering US Army. His life ended abruptly in 1859, before his 40th birthday. What do the records suggested here reveal about his personality?

In 1849, after the Mexican-American War, the people of New Mexico chose Smith to represent them in Congress. But Congress refused to seat him because of his anti-slavery stance. Newspapers across the country chronicled Hugh’s camp out on the steps of the Capitol. Many articles agreed with the Philadelphia Freeman, which praised Smith’s “fidelity and eminent services to New Mexico” March 20, 1851. “Nobody could doubt his entire competence,” reported the National Era on March 13.

I haven’t discovered letters or diaries of Smith’s, but others refer to him. Teenager John Watts’ diary notes several encounters with Smith in 1859. Once, Watts and a friend were calling on two sisters when Smith and the local doctor showed up. Watts wrote that he and his friend left, unable to compete with a lawyer and a doctor. (The emphasis is Watts’ own.) When Smith died a few weeks later, Watts described the “excellent” crowd of at least 300 at the funeral—more than he’d ever seen at one in New Mexico. Another acquaintance, James Webb, mentioned Smith’s sudden death in a letter to his business partner). Smith had “drunk hard for a long time,” and Webb wasn’t surprised by the untimely death.

Smith’s 1850s expenditures fill nearly 12 pages of a Santa Fe general store ledger. He bought at least a dozen pairs of ladies’ shoes—not the only curious purchase for this lifelong bachelor. He also bought a “fancy silk dress” for $33 (equal to a cool $870 today), hundreds of yards of fabric, and thread, needles, buttons, scissors and thimbles. Was he a tailor on the side? Doubtful, but he made sure some lady was well dressed. These purchases tapered off toward the end of his life, but his increasing acquisition of whiskey and wine supports Webb’s words.

More than 20 years after Smith’s death, a friend described him as a “good, industrious, careful lawyer” and an “affable” person. Though the photograph at right has no props, the hint of a smile seems to make “affable” fit perfectly.

From the records, I can surmise Hugh Smith was intelligent and principled. He was respected in his community. He had affection for a woman (or women) and appears to have given her many gifts. Yet Smith was flawed. Something drove him to drink excessively, cutting his life short. Was it the woman? Political failures? A Type-A personality? More research may answer those questions. By examining records for personality, Smith’s memory—his life’s imprint—can be more than a name followed by birth and death dates.

A version of this article appeared in the September 2009 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Updated: August 2021

Related Reads

ADVERTISEMENT