Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

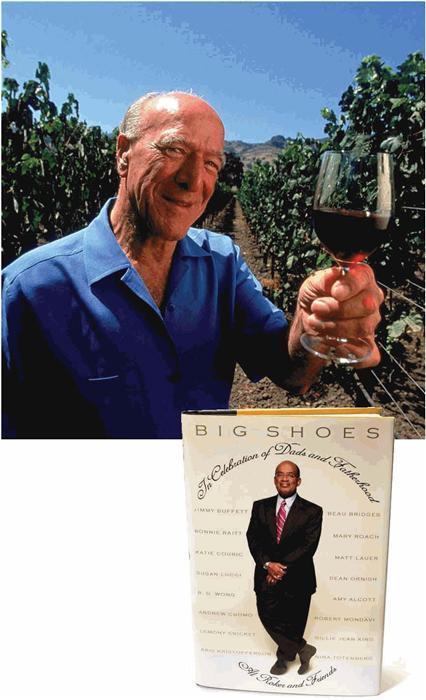

In terms of physical stature, my father was not a big man. In fact, he was so short that he could barely see over the steering wheel of his car — and other drivers could barely see him. The joke in the Napa Valley was that if you saw a car rolling down the road without a driver, it must belong to Cesare Mondavi.

To me, though, Dad was a giant. My mother taught us to appreciate good food and good wine and the family warmth and togetherness that are nurtured best at the family table. Dad was a more remote and demanding figure, but he was a wonderful father to my brother and sisters and me. He taught us great lessons about life and the best values to have and protect.

My father and mother, Rosa, came from hardworking families. They grew up on the hillsides outside of Sassoferrato, a farming and mining town in central Italy, a few hours’ drive south of Venice. Their families had been sharecroppers for generations. They lived in primitive stone farmhouses, with no heat or electricity, and had small plots of land on which they cultivated wheat and vegetables and raised rabbits and chickens. They were obliged to give about half of whatever they produced to the man who owned the land, who lived in a fancy manor house on the top of the hill.

In the early 1900s, that part of Italy was in a terrible depression, and my father and his older brother decided to try their luck in the iron ore mines of northern Minnesota. It was rough work, but the pay was better than in Italy, so my father went back, married Rosa, and brought her to Minnesota. When his brother was killed in a mining accident, Dad decided to find another line of work. He and Mom were running a boardinghouse for the Italians who had come to work in the mines, and then they added another business: a small Italian grocery store and saloon. Both of them worked liked slaves, and the winters were brutal. In the early 1920s, Dad saw a brighter future for us, and he and Mom packed us up and moved the family to Lodi, in California’s fertile Central Valley. There, Dad launched himself into something new: the wholesale fruit and grape business.

As a kid I helped load the trucks and nail together the wooden boxes we used for shipping the grapes. I got paid by the hour, plus a small bonus for every box I nailed, and over the years I was able to put a good bit of money into the bank. And it’s a damn good thing I did. One day Dad came to me with a grave expression on his face. The Depression, he explained, had hit the family hard. Very hard. He needed money desperately, and he had nowhere else to turn. So he asked me, “Bobby, can I borrow that money you’ve saved?” Dad was a very positive man, and he knew things would get better; we just had to continue to work hard and think smart. Besides, he had been through far worse back in Italy. He made me a promise: “Not only will I pay you back in full, Bobby, but I’ll send you to any university you want to go to.”

Well, Dad was able to steer us through those terrible Depression years, and he was true to his word. Of course, I had to choose the most expensive school, Stanford. The cost was a burden; we were just getting back on our feet. But he had made me a promise, and by golly he was going to keep it.

ADVERTISEMENT