Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

This is Hawaii, that mystical, magical paradise floating in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, dressed in sunglasses and a mai tai, waiting to relax the tired traveler with its salty breezes and starry skies.

But beyond the image lies a history rich in culture, in tragedy, in inspiration, a history that most visitors walk past en route to the nearest poolside lounge chair. So ditch the daydream of the tropics and learn a lesson or two about the culture and history of Hawaii.

The only royal palace in the United States, ‘Iolani Palace (South King and Richards streets, 808-522-0832, <www.iolanipalace.org>) is the emotional heart of Hawaii. It was the official residence of King Kalakaua and Queen Kapi’olani from 1882 to 1891, and the home of Kalakaua’s sister and successor, Queen Liliuokalani, until the kingdom was overthrown two years later.

The palace housed the state’s government until 1969, when construction on the current Capitol a block away was completed. By the time the legislators moved out of their cramped quarters — the Senate met in the dining room, the House in the throne room — the palace was in dire need of restoration and repair. The grand-koa (a native tree with fine, red wood) staircase was termite-ridden and the Douglas-fir floors were pitted and gouged.

The nine-year restoration, completed in 1978, cost the state $7 million. (Building the palace in 1879 cost just $343,595.)

The romance of the Hawaiian monarchy is alive in the native hardwoods and framed portraits. But like Hawaii, its beauty masks a history tortured with conflict and struggle. The grand Throne Room hosted glorious balls and receptions. But it was also the room where Liliuokalani was tried for treason by the men who seized her government.

The stately and impersonal bedrooms upstairs boast the finest in craftsmanship. But one room, Liliuokalani’s bedroom, austerely furnished with two cots, two chairs and two tables, is unforgettable. Imprisoned in this room for eight months, the shutters ordered closed so her people could not see her in the window, Liliuokalani composed “The Queen’s Prayer” and worked on a silk quilt now displayed in glass case.

‘Iolani Palace has come to symbolize Hawaii’s duality and struggle for identity in a world that has long ignored its complicated history.

The 45-minute palace tours leave every 30 minutes from 8:30 a.m. to 2 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday. Admission is $20 for adults and $5 for children ages 5 to 17.

Hawaiian Islands

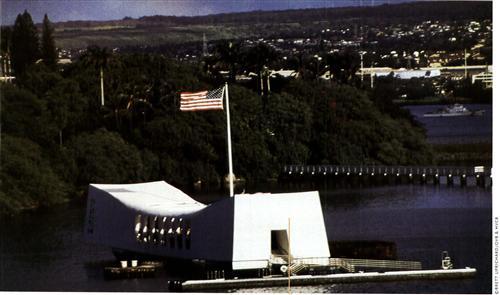

Formerly known as Wai Momi (pearl waters), Pearl Harbor has become the military focal point of the Pacific basin.

And since Dec. 7, 1941, the harbor has also become an important part of US history. On that winter morning, more than 2,300 soldiers were killed during the two-hour attack by the Japanese. It was such a surprise the USS Arizona sank in nine minutes, with 1,177 men entombed in its metal hull.

The Arizona Memorial (1 Arizona Memorial Place, 808-422-0561, <www.nps.gov/usar>) honors the marines and sailors who perished during the surprise raid. The monument draws more than a million visitors a year, most of them from Japan, who come to pay tribute to the soldiers who lost their lives.

The 184-foot open-air memorial, built in 1962, sits directly over the Arizona just 8 feet below the surface along what’s known as Battleship Row. (Four of the eight battleships docked at Pearl Harbor were sunk.) The monument houses the ship’s bell and a marble wall inscribed with names of those who died on board. The average age of the ship’s enlisted men was 19.

Hawaii for all seasons

Hawaii may not have distinct seasons, but the state does boast a culturally rich calendar. Here are the don’t-miss events of each season:

FALL

Aloha Week Festivals: Weeks-long celebration of all things Hawaiian, the Aloha Week Festivals kick off festivities in mid-September, with parades and ho’olaule’a (block-party celebrations).

WINTER

New Year’s Day: A cultural twist to a national holiday, New Year’s Day in Hawaii has an Asian flair. Celebrations are deeply rooted in Asian customs and religious traditions — demonstrating the mixing of cultures that go back to the state’s plantation era.

SPRING

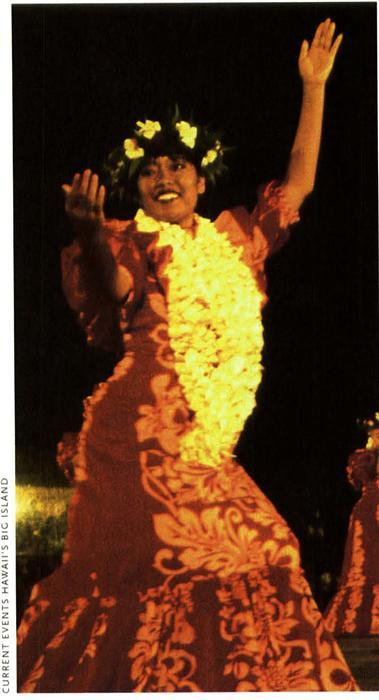

Merrie Monarch Hula Festival:

The largest hula competition in the state, the Merrie Monarch Festival, held in Hilo on the Big Island, lures thousands of well-trained dancers to compete for the prestigious titles.

SUMMER

Obon Festival: Summer marks the beginning of the obon season in Hawaii, a distinctly Buddhist ritual of honoring the dead that has evolved into a community tradition. The bon dance, held at Buddhist temples all around the state, is the focal point of the annual celebration, customarily staged with a colorful ritual of songs, dances, drummers and singers.

The visitor center is open from 7:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily except for major holidays. Tours, which are free, run every 15 minutes from 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. on a first-come, first-serve basis. Wait time may be two hours. The tour consists of a well-produced 20-minute documentary on the “day that will live in infamy” and a visit to the memorial.

Tucked away in Waipahu lies a three-acre hamlet that brings visitors back to the plantation era, what has become the foundation of Hawaii’s contemporary culture. Hawaii’s Plantation Village (94-695 Waipahu St., 808-677-0110) offers a glimpse into plantation life and insight into the state’s multicultural heritage.

The outdoor museum pays tribute to this era, with replicated ethnic dwellings representing the eight major groups that immigrated to the islands as sugar workers: Japanese, Chinese, Okinawan, Filipino, Korean, Puerto Rican, Portuguese and Hawaiian. Houses are set up with period furnishings that portray the different lifestyles and cultures of each ethnic group. The village boasts nearly 30 replicated dwellings, including a Chinese cookhouse, plantation store and community bath.

In the heyday of the plantation era, more than 40 sugar plantations utilized a private railway system that has since been restored. The Hawaiian Railway (91-1001 Renton Road, 808-681-5461, <hometown.aol.com/hawaiianrailway>) takes visitors along the rails of history on a 6.5-mile stretch of track in ‘Ewa, just south of Waipahu. The museum houses a trio of vintage diesel locomotives. The 90-minute tour is a leisurely journey through Hawaii’s plantation history.

Though the Pacific Tsunami Museum (corner of Kamehameha Avenue and Kalakaua Street, 808-935-0926, <www.tsunami.org>) focuses on the effects of the town’s two lethal tsunamis of the past century, the museum also documents the entire history of Hilo. Tsunamis are ocean waves triggered by a disturbance of the ocean floor, often caused by earthquakes or landslides.

An earthquake in Alaska in 1946 sent tsunamis racing south to Hawaii. On the morning of April 1, they hit the shores of Hilo at a height of 57 feet, destroying half the town and killing 96 people.

Only 53 days after the official reopening of Highway 19 in 1960, another tsunami, this one from off the coast of Chile, slammed the city and claimed 61 lives. Footage and photos of the tsunami complete the storytelling. One photo shows Hilo residents standing on the shore, waiting, just minutes before the wave took their lives.

The museum is open 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Saturday.

On Jan. 6, 1866, King Kamehemahe V sent nine men and three women suffering from leprosy into exile on a lonely shore on Moloka’i. More than 11,000 lepers arrived between 1865 and 1874, left to die on one of the world’s most beautiful and secluded shores, Kalaupapa, “The Place of the Living Dead.” Hidden along the north coast of Moloka’i, cut off by towering 2,000-foot cliffs, Kalaupapa peninsula still harbors the suffering of centuries past. It’s the site where Father Damien, who arrived at the leper colony in 1873, built shelters and farms for the exiled patients. A cure for leprosy was discovered in 1946, but more than 60 former patients chose to live out their lives on the lonely peninsula, living in whitewashed houses with statues of angels in their yards.

At Kalaupapa National Historic Park (808-567-6802, <www.nps.gov/kala>), visitors can either hike or ride a mule down a 2.9-mile cliff trail with 26 switchbacks. No one under 16 years old is allowed at Kalaupapa, making it the only child-free county in the United States. The visitor center sells ornaments and artifacts made by patients.

Rides with Moloka’i Mule Ride (808-567-6088 or 808-567-7550, <www.muleride.com>) include a ground tour and picnic lunch. The Father Damien Tour (808-567-6171) starts at 10 a.m.

From the November 2002 issue of Family Tree Magazine

ADVERTISEMENT