Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Much of our national identity has been shaped by happy accident. Case in point: In 1620, Mayflower passengers left England bound for Virginia, but a fluke of fate landed them in Massachusetts. (Learn more about those hardy souls in books from the Massachusetts Society of Mayflower Descendants <www.massmayflower.org>.) But whether or not your Bay State ancestors descend from the pilgrims, plenty of fortunate finds await you around every corner.

Charmed past

The Mayflower pilgrims didn’t have the place to themselves for long. More than 20,000 people immigrated to New England from 1620 to 1642, during a period known as the Great Migration. Many settled in Plymouth Colony — today’s Plymouth, Barnstable and Bristol counties — and in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, comprising the towns north of the Merrimack River plus Suffolk County and what’s now New Hampshire. In 1691, a charter united the two colonies and added parts of Maine and Nova Scotia.

Religious intolerance spurred dissenters, such as Roger Williams and Anne Hutchinson, to depart for friendlier pastures and establish towns elsewhere in New England. Bay Staters spread across the country much like the trees of native folk hero John Chapman (aka Johnny Appleseed) — in fact, an estimated quarter of the entire US population has roots in Massachusetts. Plenty of people stuck around, too: Post-Revolutionary War growth of cities and small towns, as well as an influx of Irish, French Canadian and other immigrants, made Massachusetts one of the most densely populated US states by the end of the 19th century. Due to boundary disputes with bordering Rhode Island, New Hampshire and Maine, ancestors who lived near state lines often left records in multiple locations, so you may need to check more than one state.

Resource serendipity

Few states match Massachusetts’ bounty of records. Before delving into them, let’s dispel a myth: Not everything about early residents is in print or online. More records than ever before are being digitized or added to databases, but orderly Puritan town clerks’ sheer amount of documentation means it’d take ages to publish it all. But you’ll find plenty of family history fodder in these records:

• Census: Federal census records for Massachusetts cover 1790 (the first US head count) through 1930, with two exceptions: The 1800 census lacks Boston and parts of Suffolk County, and the Union Civil War veterans schedule is all that’s left of the 1890 count. Find census records on microfilm at large public libraries, the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) <archives.gov>, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ Family History Library (FHL) <www.familysearch.org> and its branch Family History Centers (FHCs; use FamilySearch to find one near you), as well as on the subscription site Ancestry.com <Ancestry.com >. You also can access census records online for free through libraries that subscribe to HeritageQuest Online <heritagequestonline.com> or Ancestry Library Edition.

Use the Massachusetts and Maine Direct Tax List of 1798 to substitute for the incomplete 1800 federal census. It’s available on FHL microfilm and in the New England Historic Genealogical Society’s (NEHGS) <www.newenglandancestors.org> members-only databases (rates start at $75).

The only surviving state censuses, taken in 1855 and 1865, let you trace ancestors during a peak immigration period. They list everyone in a household. Large libraries including NEHGS and the FHL have Ann S. Lainhart’s books of every-name indexes for many towns; the state archives and the FHL have microfilmed schedules. (To find the FHL film, run a place search of the online catalog on Massachusetts, then click on the Census — 1855 heading.)

• Town: As in other New England states, you’ll find most Massachusetts records on the town level, rather than in county offices. Birth, marriage and death records date from the colony’s founding. Many through 1850 or later have been published — find titles by running a keyword search of the FHL catalog on the town name plus vital records. The Boston Public Library <www.bpl.org> collection covers much of the state. Some records, such as Provincetown’s (1698 to 1859) and Dorchester’s (deaths from 1732 to 1781), are in NEHGS’ online databases. Only Boston neglected to record births between 1800 and 1849 — use city directories, first published in 1789, to fill the gap.

In 1841, the state required towns to submit copies of vital records. You can search these in NEHGS’ online databases, or request records through 1915 from the Massachusetts archives. Thereafter, contact the state registry of vital records (see resources).

Towns also kept school and tax records, business licenses, meeting minutes, livestock earmarks (to show ownership) and, for voting purposes, lists of freemen (landowning men of legal age — usually 21 but as young as 16). Call your ancestral town clerk to learn the records’ whereabouts, or consult Ann S. Lainhart’s Digging for Genealogical Treasure in New England Town Records (NEHGS, out of print). You can search a descriptive index and catalog for 18 volumes of documents from the state archives at <www.sec.state.ma.us/arc/arcidx.htm> (click Our Collections).

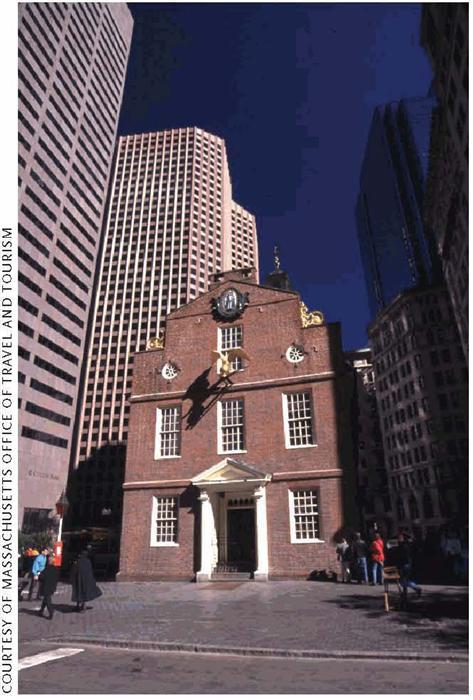

Patriots made stirring revolutionary speeches in the Old State House, built in 1713 for the Massachusetts Bay Colony government.

You’ll also find various indexes on FHL microfilm (which you can borrow through an FHC near you), in Ancestry.com’s databases and elsewhere on the Web. A Google <google.com> search on massachusetts freemen, for example, turns up a 1630-to-1636 list <www.winthropsociety.org/doc_freemen.php>.

• Probate and land: These records, which counties keep, pose an exception to the New England town-records quirk. But pinpointing your ancestors’ county can be tricky due to changing borders. For example, Suffolk County, home to Boston, originally included parts of Norfolk and Worcester counties — in 1793, residents of the town Dedham “moved” from Suffolk to Norfolk county. Use Massachusetts GenWeb <rootsweb.com/~magenweb> or William Francis Galvin’s Historical Data Relating to Counties, Cities and Towns in Massachusetts, 5th edition (NEHGS, $9), to sort out the details.

Once you know the county, consult The Genealogist’s Handbook for New England Research, 4th edition, by Marcia Melnyk (NEHGS, $19.95) to learn where to look for records you need. Most counties held on to their original land and probate records, but you may or may not find an index. Published or microfilmed indexes for probate records in several counties, including Middlesex, Norfolk, Suffolk and Worcester, are available at NEHGS, the FHL and other libraries. Note that five Bay State counties had multiple deed offices.

• Military: Massachusetts men served in all the Colonial wars, including conflicts with American Indians (such as King Phillip’s War), and those involving European nations (the French and Indian War, for example). John Adams and other local sons stood at the forefront of the revolutionary fervor. Paul Revere’s April 18, 1775, midnight ride is well-known, as are the next day’s shots “heard ’round the world” from Lexington and Concord.

Research patriot ancestors in the 17-volume Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War, available on Ancestry.com and a $26.95 CD. The state archives’ military records span the 17th through 20th centuries, including military rolls and accounts, state pensions, Maine bounty-land grants for Revolutionary War veterans and Civil War muster rolls — see <www.sec.state.ma.us/arc/arcgen/genidx.htm> for more details. The state National Guard Military Museum and Archives <www.mass.gov/guard/Museum/Information.htm> has records of the Massachusetts National Guard, which dates to 1636, including soldiers and sailors (1775 to 1940) and Civil War volunteer regiments.

Check Cyndi’s List <cyndislist.com/ma.htm#military> for links to online rosters and regimental histories. You’ll also find microfilmed records, such as Revolutionary War muster rolls and Massachusetts Civil War volunteers, in the FHL’s online catalog.

• Immigration: Massachusetts ports such as New Bedford, Gloucester and Boston (the second-largest immigration port after Ellis Island) welcomed newcomers from all over the world during the 19th and early 20th centuries. You can search an in-progress database of Boston arrivals since 1848 for free at the state archives Web site. Microfilmed passenger lists are available at the two NARA facilities in Massachusetts (see resources) and at the FHL.

You can do a lot of research from afar, but offline resources at the Massachusetts state archives, Boston Public Library, NEHGS and many town historical societies are excellent reasons to plan a trip to the Bay State. Add the ambiance of history, and you won’t need any happy accidents to discover your Massachusetts roots.

From the August 2006 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

ADVERTISEMENT