Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

I was trying to make the research mistake I’m about to confess seem less odious because, well, I don’t want you to hold it against Family Tree Magazine, but then I realized that’s counter to my point that anyone can make a mistake. Conflicting records contributed to my error, but so did I, by relying on others’ research including (gasp!) information found in an online tree. Here goes:

My third-great-grandfather Edward Norris was an Irish immigrant and a stonecutter in Cincinnati. I had him born in 1827, based on his age of 33 in the 1860 census. He was 40 in the 1880 census, but that would make him only 10 was he was married May 22, 1850 (the date on his digitized marriage license, restored after a Cincinnati courthouse fire in 1884 destroyed the original), and 13 when his first child was born in 1853. I can’t find the family’s 1870 census record.

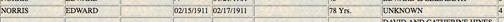

His death date in my family tree for years was Feb. 15, 1911. That’s the date my late aunt recorded back before online genealogy took off. It’s in the burial index of St. Joseph “New” cemetery, where his wife and several children are buried.

An image of the corresponding burial card (not shown), which I found in a distant cousin’s online tree, gives Edward’s death and burial dates, age, and his late residence in the City Infirmary (his wife died in 1897).

This Edward Norris died at age 78, putting his birth in 1833. (This would have him married at 17, and age 20 when his first child was born.)

I busied myself with other research, but eventually it dawned on me that I couldn’t find Edward in the 1900 or 1910 census, or any city directories after 1890. Nor could I find an official death record or an obituary. A death in Ohio in 1911 should appear in city registers or a state death certificate (these begin in 1908 in Ohio), or both.

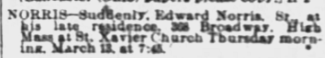

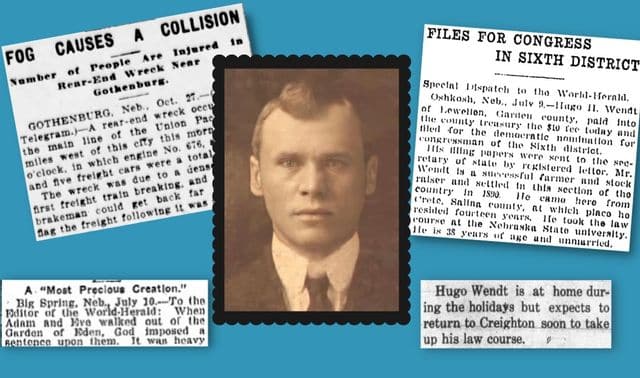

Then I found this in the Cincinnati Enquirer, March 12, 1890.

The death announcement reads “Suddenly, Edward Norris, Sr., at his late residence, 368 Broadway. High mass at St. Xavier Church, Thursday morning, March 13, at 7:45.”

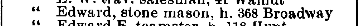

His address is 368 Broadway in the 1880 census and in this 1889 city directory (digitized in the Cincinnati library’s Virtual Library):

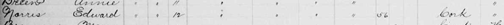

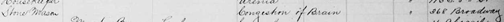

A county death register (digitized as part of this collection on FamilySearch.org) also gives this address. The death date is March 12, 1890, when Edward was 56 (so, born in 1834):

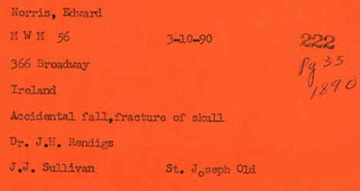

The cause, “congestion of brain,” is a swelling that could’ve resulted from the accidental fall referred to in this index card, created years ago from city death registers:

A fall is consistent with the “suddenly” description in the newspaper announcement. The death date is March 10 (not 12). The burial place is St. Joseph Old, another cemetery (Edward isn’t in that cemetery’s online index, though I’ve heard from other local researchers the index is incomplete. Looks like a visit is in order).

I’m pretty confident I was wrong all those years about when Edward died. In hindsight, the 1911 burial card has no family names or address to help identify him. The card may have been for another Edward Norris, a common name, although I can’t find a death record for that person. I wonder if someone recorded the wrong date on the burial card (though mistaking 1890 for 1911 is hard to imagine). So there’s still a mystery.

In our video class 12 Ways to Diagnose (and Treat) Errors in your Research, available in Family Tree Shop, you’ll learn ways to recognize and treat such errors. Takeaways from my experience include:

- Always seek the original record, and then evaluate the information that potentially identifies it as your ancestor’s record.

- Know how you arrived at each “fact” about your ancestor. If you got there with help from another person’s research, examine how that person came to the conclusion he or she reached. Citing sources is an important part of this process.

- Look for multiple records about the same event, and pay attention to the little alarms that go off in your head when records don’t match up.

ADVERTISEMENT