Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Exploring your family history can be like opening Pandora’s box—you don’t know what’s going to come out once you begin research, and revelations can’t be forgotten or returned to the box. You might make discoveries that help you feel more connected to others or strengthen your sense of identity. But you may also come face to face with your ancestors’ bad behavior, tragic experiences or long-forgotten secrets.

Turning up difficult information, you may feel angry, betrayed, embarrassed, confused, repulsed or ashamed. What can you do with these feelings? Experts recommend six steps:

- Confirm your discovery. Do careful research to verify what you’ve learned.

- Understand the context. Study the circumstances or historical context surrounding the event or situation.

- Learn what happened next. See how your ancestors, their loved ones and communities responded. Did anyone provide support or assistance? What did those involved do?

- Express your feelings. Talk to a trusted friend. Write in a journal or on a blog. If appropriate, join a group like Facebook’s DNA Surprises Support Group or NPE [Not Parent Expected] Friends Fellowship, or seek professional counseling. (Find additional resources.)

- Give credit where it’s due. Identify positive character traits or actions shown by your ancestors, their children or other affected loved ones. Celebrate their determination, courage, resilience or even their will to survive.

- Take positive action. Find ways to help prevent possible recurrence of similar trauma today or to help others better understand the full history of those affected.

We’ve collected seven stories below that are startling, in one way or another, from genealogists across the United States. Each person has found a way to cope with—or at least try to make sense of—long-buried family secrets. If you find yourself needing to make peace with the past, perhaps there’s a solution for you here in the case studies below.

Note: The stories that follow contain details that some readers might find upsetting, so continue with caution. Certain names have been changed to protect the individuals’ privacy.

Defusing a DNA Bombshell

In January 2019, Ray Santos received DNA results that shocked him. According to his results, Santos’ maternal grandfather—whom he adored and who was still alive—isn’t related to him. And thus, that grandfather isn’t the biological father of Santos’ mother.

At first, Santos kept a clear head, carefully reviewing his results to confirm this unexpected truth. But then his emotions kicked in. His mother purchased the test as a gift for him, and was eagerly awaiting results that he suddenly didn’t want to share. Then he realized his grandfather might not even know. Santos wanted time to absorb the news and plan his next steps.

After getting advice from his father, Santos told his mother that same night. The conversation went well, thanks in large part to his mother’s unfailing sense of humor. But the family was shaken, and Santos realized the revelation could affect others in the family. Only half-jokingly Santos said, “There needs to be a ‘bombshell DNA results’ support group.” (As we’ll discuss later, these kinds of communities exist!)

Remembering the Enslaved

Deborah Abbott, who has a doctorate in counseling and human development, is a nationally known genealogy educator who has African American roots. Her family came from the South, but her relatives didn’t talk about their hardships there once they moved north. “When I was growing up, I didn’t think slavery had any relevance to my life,” she said.

But that changed in the 1970s, when Abbott was a young adult. While watching “Roots” with her grandmother, Abbott heard her saying to the screen, “They never would’ve done that during slavery.” When asked further, Abbott’s grandmother told her that her grandmother (Abbott’s great-great-grandmother) was a slave. Abbott later learned that Caroline, her grandmother’s mother (Abbott’s great-grandmother), was also born into slavery. Slavery wasn’t so far from Abbott’s time, after all.

“I can’t point to a single moment of grief or anger about what slavery meant for me,” Abbott said. “Knowing my ancestors were enslaved is something I just grew up [with]. It can make some people distrust or hate white people now, even though people today aren’t responsible for what was done back then.”

Abbott’s ancestors were considered someone’s property. Just a few generations ago, they couldn’t read or write or move around at will. However, Abbott has earned a doctorate and traveled the world. “The reason I have what I have today is because of those who sacrificed so I could go to school and vote,” she said. “I benefit from their actions.”

Now, Abbott’s lifework includes teaching others about slavery and how to trace enslaved ancestors. She uses her own family’s stories woven through her lessons. For example, one lecture includes an Underground Railroad re-enactment that uses names from Abbott’s family. One enslaved woman holds a baby named Caroline, and the characters have the same names as her ancestors’ slaveholders in real life.

Responding to Historical Wrongs

Lauren Peightel learned that one of her ancestors, Samuel Blodgett, helped create the canal that powered the industrial city of Manchester, N.H. (including the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company, the largest cotton mill in the world). Samuel’s son, Captain Samuel Blodgett, Jr., traveled to Boston and made money working with the East India Trading Company.

At the time, the East India Company profited from the slave trade. Peightel, who coordinates genealogy and multicultural programs for the Indiana Historical Society, was horrified at the thought that her family made its fortune benefiting from the slave trade.

Newly tasked with developing multicultural programming, Peightel had just started a project celebrating African Americans in Indianapolis, Ind., when she learned about her family’s connection to the slave trade. Her intern, RaeVen Ridgell, challenged her, asking what she would do with the information, and how she was going to use her privilege to help the community.

“We can’t be responsible for the history, but we are responsible to the history,” said Peightel. “Even if I don’t know my ancestor’s exact role in profiting from the slave trade, I can continue to educate myself and make sure I’m shining a light on the whole story. I can listen more to communities who haven’t been treated well and learn how the history of my people affected the history of other people.”

Grappling with Family Betrayal

Melissa Barker, archivist for Houston County, Tenn., found unusual court records involving her ancestors. In 1940, her great-grandfather committed his wife (Barker’s great-grandmother) to a mental hospital and then married another woman two weeks later. Barker’s great-grandmother spent 15 years in the facility before being “cured” and discharged. “They literally dragged her out of the house,” Barker said.

Barker’s great-grandmother died 20 years later. Among her possessions were a card that she always carried in her wallet which said she was no longer “crazy.”

“I couldn’t believe it!” Barker said. “My grandmother was the youngest of 14 children, and almost all her brothers and sisters were married or adults. I wondered why they didn’t step in and stop it. My grandmother said they were powerless because her father had all the power to do what he did.”

For the most part, Barker took the discovery in stride. “I usually approach things like this wanting to know why someone did what they did instead of [feeling] anger,” Barker said. And as a genealogist, she had heard of cases like this and was aware of women’s general lack of rights in those days.

While Barker said she hadn’t found a justification for the commitment to the mental hospital, she speculated her great-grandmother had undiagnosed postpartum depression or some other mental ailment. “I’m not saying my great-grandfather was right in doing what he did,” said Barker, “But anyone would be affected from [even] just having 14 children!”

Choosing New Ancestral Heroes

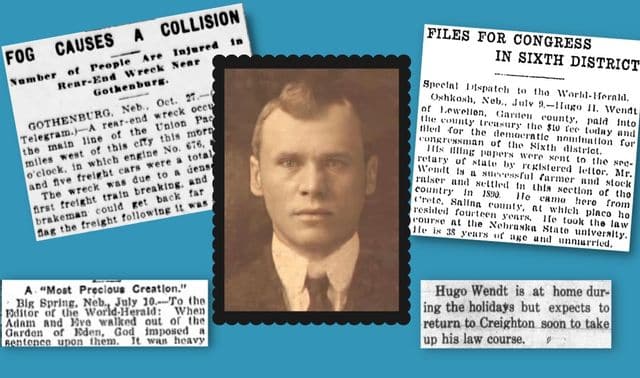

In preparation for a trip to Ireland a few years ago, Angela Baker tried to identify the overseas hometown of her O’Connor ancestors, immigrants who settled in Iowa. She stumbled upon a jarring newspaper article about the father of the family: “Daniel O’Connor, of Case County, Attempts an Outrage upon His Own Daughter.”

Daniel abused his wife, Catharine, prompting her to return to her mother’s home in Connecticut—leaving their children behind. He then tried to sexually assault his younger daughter, but the daughter escaped to an uncle’s house. The police found Daniel locked in his room, and he committed suicide before they could arrest him.

“It was heart-wrenching,” Baker said. “I’d been so proud of our O’Connor name. I’m still trying to make peace with how Catharine left her children with that monster. She may have been forced to do so, to escape with her own life.”

Further research revealed the name of Catharine’s Irish hometown: Leitrim. Barker visited the town and the church where another line of ancestors, the Caseys, were baptized. While there, she chatted with some distant relatives. “My Irish pride has shifted from the O’Connor name to the Caseys and her maternal side, the McKiernans,” Baker said.

Another researcher, Cassandra Neilsen, has also selected a new hero after uncovering a troubling era in her family history. Nancy Katherine Nash (born during the late 1830s) lived in Illinois most of her life, where she married and had seven children. Her death certificate listed her parents as Andrew J. Nash and Leah Misenheimer.

The problem? Andrew Nash, a “notorious rake and drunk,” was married to Leah Misenheimer’s sister. Indeed, he confessed to an affair with his wife’s sister, and fathered three children by her. What’s more, he stabbed a man in 1851 in a drunken rage, going on the lam. The authorities eventually caught up with him, sentencing him to be hanged. Though his sentence was commuted to life in prison, he hanged himself.

In response, Neilsen claimed Nancy as one of her heroes. “She went on to make her life her own and not let the stains of her past determine her destiny,” she said. “She married respect[ably], raised her own family and became a pillar of her community.”

Though Neilsen was initially shocked by Nash’s behavior, she accepted he was gone now. “I can’t change the past,” she said. “[But] I can take a page from my grandmother’s book and make my life my own.”

Understanding Generational Trauma

Jackie Dorman knew her family’s secret long before she understood it as such. She was sexually abused by her step-grandfather, George, from age 4. “I know my mother knew about it, because I later realized he abused her as well,” she said. “Nothing was ever done about it. It was the 1950s and the 1960s, before the era when sexual abusers were really called out for it.”

Her family never talked about it when Dorman was young. “My grandma was Victorian-proper: Appearances mattered, and this kind of thing couldn’t happen in a good family,” she said. Only after years of counseling did she finally discuss it with her siblings—one of whom also admitted to being abused—and confront the step-grandfather, who cut her off from her own extended family.

When Dorman eventually began researching her family history, a truism from counseling occurred to her: Abuse tends to cycle through generations. Following from murmurs that something was “askew” with George’s father, she traveled to a courthouse in New Jersey. There, she learned he had been arrested for gross sexual imposition of a 12-year-old. “There it was, in black and white. The shock of finding that in print took my breath away,” Dorman said. “There were four generations—at least—of trauma and abuse: George’s father, George, my mother, and me.”

Discovering this backstory didn’t excuse George or make it easy for Dorman to forgive him. But the knowledge was crucial as she moved forward. “I hate to say it, but it was healing to find that out,” she said. “It allowed me to feel compassion as well as repulsion, like the ends of a continuum.”

The most important effect was the awareness that she broke down a devastating cycle. “I’m a powerful change agent who has eliminated that lineage of abuse. My children and grandchildren, if I’m blessed to have them, may not have to deal with it,” she said. “If they do, it won’t be because it was passed down from my generation.”

Handling Genetic Revelations

Lisa Cole is a nurse and genealogist in Uniontown, Penn., who discovered a half-sister through DNA. Her biological father had a girlfriend, and the relationship produced a daughter they gave up for adoption. Cole found that daughter, but the daughter didn’t want to pursue a relationship.

The story unfolded over the course of two weeks. “I thought I was handling it fine,” Cole said. “All of a sudden one day, I broke down. My husband said, ‘A little more than you thought, isn’t it?’”

Cole now administers the DNA Surprises Support Group, a closed Facebook group with around 10,500 members. The forum collects stories that range from exciting to heartbreaking.

One frequently discussed scenario is someone discovering their “dad” isn’t their biological father. “It pulls the rug out from under them because that’s how they identify themselves,” Cole said. “There’s [also] a lot of animosity toward their moms: ‘How come she didn’t tell me?’ Some people haven’t told another soul in their family, and some are scared about their relatives finding out. Just hearing that other people may be going through similar things can mean so much.”

According to Cole, group members help each other through different stages of the process. She said people struggle when discoveries are still fresh, but members find solace in reading other people’s experiences, tips and feelings. She’s noticed that some who were struggling several months before now comfort newer members. “They realize they may need to give it time, [but] that it’ll get better,” she said. “Even if you don’t get the happy ending you want.”

“They learn not to discount the family they grew up with. They’re still your family,” Cole said. “And now I can see that some who were struggling several months ago are comforting the new ones who are coming in.”

The group often instinctively knows what not to say, since many have experienced the sense of dislocation that can come with a DNA surprise.

If you’re helping someone process unexpected DNA results, don’t minimize their experiences. According to Cole, these revelations are always a big deal, even if they don’t have a big impact on their lives. After, all, these discoveries often affect deeply held identities.

“They need to hear truth, not placating,” Cole said. “Let them cry for five hours or talk about their memories, if they want to. They need to let it out.”

Whether a family history surprise came via documents or DNA, Cole suggested bringing your proof to share. She also suggested delivering the information in the appropriate time and place—for both you and the affected person. According to Cole, you shouldn’t approach the relative if you yourself are angry or hurt. And when you’re ready, Cole suggested doing it in a neutral location, preferably alone. “You don’t want them to feel like they’re being attacked or bombarded or exposed,” she said.

Books and Memoirs about Handling Family Secrets

- Family by Ian Frazier (Picador): An acclaimed writer turns his attention to 200 years of his family’s middle-class history, revealing their little dramas in the larger picture of their historical context, from the Revolutionary War to the 20th century.

- Five-Finger Discount: A Crooked Family History (Random House) and Murder in Matera: A True Story of Passion, Family, and Forgiveness in Southern Italy (Dey Street) by Helene Stapinski: A journalist traces her less-than-ennobling family history through the criminal culture of Jersey City, N.J., and back to the mythologized crime of her immigrant ancestor in Italy.

- Hidden Inheritance: Family Secrets, Memory, and Faith by Heidi B. Neumark (Abingdon Press): A Lutheran pastor discovers her Jewish roots and learns of their Holocaust trauma. Her genealogical journey becomes a spiritual one as she challenges her faith and identity and looks difficult history in the eye.

- Prague Winter: A Personal Story of Remembrance and War, 1937–1948 by Madeleine Albright (Harper Perennial): The former Secretary of State reflects on her discovery of her Jewish family’s WWII experience and reflects on their experiences and secrets kept for decades.

- The Slaves Have Names: Ancestors of My Home by Andi Cumbo-Floyd (CreateSpace): A white woman researches the identities and stories of the enslaved people who lived on her family’s plantation and confronts the culture of silence that had kept them hidden from history.

A version of this article appeared in the September 2019 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Related Reads

ADVERTISEMENT