Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

While combing through old records, you’re bound to run across a common issue: finding the same name for different people. How can you tell if a series belongs to the same person? Or do they belong to more than one person by the same name? This quick genealogy case study is a great example of how to determine this. In it, I illustrate important tips to help you recognize your relatives on record trails that may be crowded with their likenesses.

My husband’s grandfather was John Thomas Morton. He was born in Eskdale, Kanawha, West Virginia in 1917 to Charles Morton and Valeria Epling. The U.S. census trail leading back into John’s childhood reveals a few men named Charles Morton living in the vicinity of John’s birthplace. However, Valeria’s unusual name helped me to recognize his family’s entries on census records and learn these tidbits about Charles:

| Census Year | Census Place | Name | Estimated Birth Year | Birth Place |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1940 | Sherman, Boone, WV | C.C. Morton | 1889 | Virginia |

| 1930 | Sherman, Boone, WV | Charles Morton | 1889 | Virginia |

| 1920 | Cabin Creek, Kanawha, WV | C.C. Morton | 1889 | Virginia |

Next, I came across a death certificate for a Charles Clay Morton. He was born in Virginia on 3 July 1888 to Thomas Morton and Willie McGraw. His spouse’s name doesn’t appear. Information for the document was provided by Clay Morton. The family’s census records included a son named Clay, who could have been given his father’s middle name. Analysis: the initials C.C. and the name Charles both fit; the birthdate was close; the birth state was correct; and a child’s name fit. Clay would have had firsthand knowledge of his father’s name and most likely had knowledge of his grandparents’ names as well. On the other hand, he might not have known his father’s birthdate or place and could have gotten those wrong.

The same person? Or someone different?

Then a delayed birth record surfaced for a Charles Morton born 30 July 1883 in Kanawha, West Virginia. The family lived here during John’s early childhood. I imagine the date, “30 July 1883,” could be a mistake. It could have easily been miswritten, misread, or become transposed in someone’s memory, as “03 July 1888.” The birth state could have gotten confused: West Virginia used to be part of Virginia and still had a similar name. This Charles was even born in the county where “my” Charles resided. However, this Charles Morton was the son of Alex Morton and Lucy Halstead. Information was provided by this Charles’s older sister; even if she got his birth date wrong it’s unlikely she got both her parents’ names completely wrong.

Yet another possible instance of the finding the same name, but not necessarily the same person. So which was “my” Charles Morton?

A breakthrough discovery

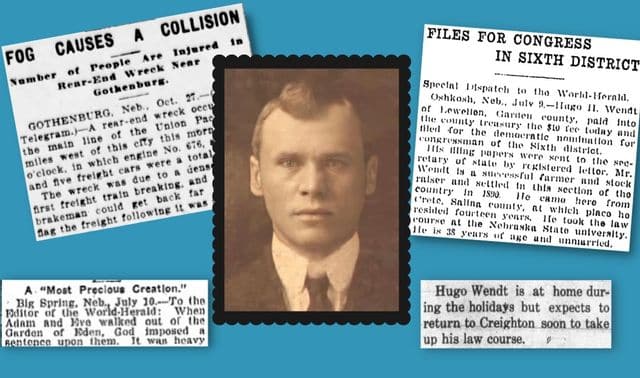

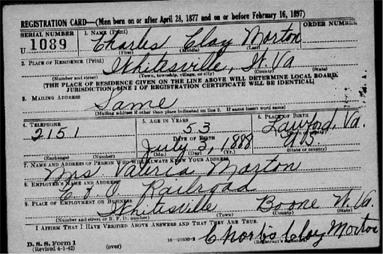

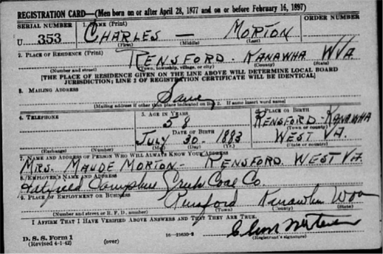

The 1942 draft registrations for both men, found on the free FamilySearch.org, set things straight:

The first record clearly identifies Charles Clay Morton as the spouse of Valeria Morton, along with the 1888 Virginia birthdate. Plus, his residence in Boone County in 1942 is consistent with his 1940 census residence. The second entry distinguishes the Charles Morton of the 1883 birth in Kanawha as a spouse of Mrs. Maude Morton. The signatures of the two men (especially the surnames) are distinct. While several individual pieces of evidence could be disputed, taken as a whole, the compelling evidence distinguishes the identities of these two men.

How to distinguish between similar-looking individuals in records

While this is a fairly simple example, the principles shown here also apply to more complicated research problems. Here are three tips to keep in mind next time you come across possible historical record doppelgängers:

- When you come across the same name, learn everything you can from the record trail leading to “your” person. When questions came up regarding Charles’ identity, I went back to what records about his son had already revealed about him. Record trails usually work backward in time: you often first encounter relatives in records created later in their lives. But sometimes you’ll have to look across a person’s lifespan to make sense of what you see.

- Research and compare all records that seem to pertain to this name. If they belong to different people, you will likely start to see patterns that help you group the records by person, such as a specific relationship or similar birth information. If similar, but apparently conflicting, records end up belonging to the same person, you may eventually notice circumstances that allow for apparent discrepancies, such as a second marriage.

- Try to determine who provided critical information in each record. This person is called the “informant.” An informant’s probable reliability depends on the likelihood that they would have firsthand knowledge of a piece of information. For example, Clay Morton would have had firsthand knowledge of his father’s full name, especially since he had his father’s middle name. He would not necessarily have had firsthand knowledge of his father’s birth. Therefore, take things like this into consideration when evaluating this type of evidence.

ADVERTISEMENT