Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

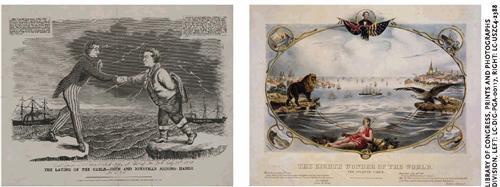

If your ancestors immigrated before the mid-19th century, their separation from home and family across the Atlantic was more complete than we can even imagine in this era of instantaneous global communication. A letter took at least 10 days by ship to reach Europe; not even the wealthy could get word overseas any faster.

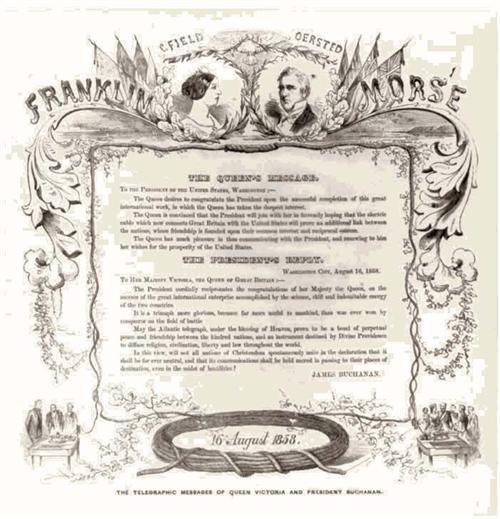

In New York City, a 100-gun salute greeted the news that telegraphy had at last bridged the Atlantic. Church bells rang, flags flew and all night long, the city’s lights glowed with celebration. Cyrus West Field, the American businessman behind the project, was hailed as a modern Prometheus.

The “glorious” triumph would last only one month, however. Beneath the waves, the cable’s insulation began to deteriorate. An excess of voltage, applied in hopes of speeding transmission — that historic first telegram took 16 ½ hours to transmit — fried the already vulnerable wires.

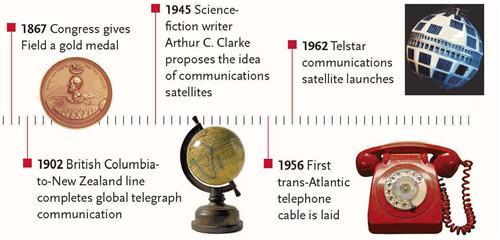

Trans-Atlantic telegraphy wouldn’t be permanently restored for eight years, when the largest ship of the day, the Great Eastern, succeeded in laying a new cable in July 1866 — finally realizing a dream that dated almost to the invention of the telegraph.

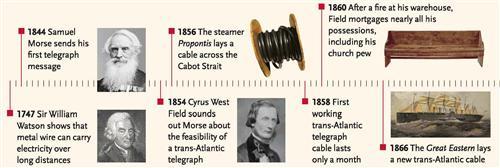

Even before Samuel Morse sent his historic “What hath God wrought?” message in 1844, he’d experimented in New York Harbor with a submerged wire insulated by India rubber and tarred hemp. Besides the sheer length and weight of cable required to span the Atlantic, the technical challenge was how to keep the electric current from escaping into the ocean.

Gutta-percha, a sticky gum from an Asian tree, arrived in Europe just in time. Scottish surgeon William Montgomery, who’d encountered gutta-percha while employed by the British East India Co., brought some home in 1842 to use for surgical gear. In 1850, a gutta-percha-coated cable crossed the English Channel, and within two years, telegraphy linked London to Paris.

Enter Cyrus West Field. Born in Massachusetts in 1819, a teenage Field started out as an office boy for A.T. Stewart & Co., New York City’s first department store. By age 20, the enterprising Field was a partner in the E. Root paper company. He retired at 33 with a fortune of $250,000. Field would die in 1892 bankrupt from bad investments, but not before realizing his vision for a trans-Atlantic cable.

He’d gotten that idea in part from Nova Scotia telegraph engineer Frederick Newton Gisborne, who’d conceived the more-modest notion of linking Cape Ray, Newfoundland, to Aspy Bay, Nova Scotia, across the Cabot Strait. The initial benefit was that passing ships could drop off the latest news from Europe, to be transmitted to New York City 48 hours before the ships could get there. Although Gisborne’s effort collapsed, it earned him an invitation to meet Field. With Field’s backing, Cabot Strait was crossed by cable in 1856.

Next, Field set his sights across the Atlantic. He founded the Atlantic Telegraph Co., seeding it with his own capital and convincing the British government to subsidize the project with ships and 14,000 pounds a year. Similar backing narrowly passed the Anglophobic US Congress, squeaking through the Senate by a single vote.

An initial effort in 1857 set off from the Irish coast near County Kerry’s Ballycarbery Castle. But after two cable breaks, work was abandoned until the next summer.

A total of 3,000 nautical miles of cable were produced for the project, including 700 miles to replace cable lost in the 1857 attempt. The cable comprised seven copper wires, each weighing 107 pounds per nautical mile, wound with tarred hemp, then sheathed in a spiral of iron wires. The Agamemnon and Niagara each carried half the Atlantic-spanning length, meeting in the middle of the ocean June 26, 1858, to splice the pieces together. After three breaks, however, the whole process had to be repeated, splicing again on July 29.

Public support evaporated. It took Field six years to raise the funds to try again, and several more failures before the Great Eastern successfully laid 2,300 nautical miles of cable in 1866. When the ship also recovered a cable that had snapped in a try the year before, two permanent working telegraph lines connected Europe with America.

Wire Tapping

Dial up these resources to learn more about the trans-Atlantic telegraph cable:

• American Experience: The Great Transatlantic Cable

• The Atlantic Cable by Bern Dibner

<www.sil.si.edu/digitalcollections/hst/atlantic-cable>

• BBC Radio: “A Wire Around the World” broadcast

<www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/science/wirearoundtheworld.shtml>

• History of the Atlantic Cable and Undersea Communications

• Locust Grove: The Samuel Morse Historic Site

2683 South Road, Poughkeepsie, NY 12601, (845) 454-4500, <www.lgny.org>

• Online: 150 Years on the Net

<www.ptt.dk/150aar/150aar_eng>

• Transatlantic Telegraph

<www.ns1763.ca/victco/cabotcablem.html>

• Underwater Web: Cabling the Seas

<www.sil.si.edu/exhibitions/underwater-web>

ADVERTISEMENT