Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

The history of Stockholm, Sweden’s capital, stretches back to the 13th century, when the city was a prominent trading post.

My great-grandfather Gustav Fryxell came to America in 1876 with his brother John. In a book about his life, John recalls the impoverished life they left behind in rural Sweden: “I remember one fall when mother had made a coat for Gustav, then 5 or 6 years old. He was very proud of it, but one day when he was out picking berries he lost it. How we looked for it — mother, father, all of us! But we did not find it, and all that winter Gustav could not go out when it was cold because he had no coat.” Buying fabric to make a replacement coat, of course, was out of the question. Another time, John recalls when the family’s only cow starved to death and “father got the minister to draw up a letter petitioning the neighbors to help us secure another. Father being ashamed, I was sent from house to house with it.”

Is it any wonder, growing up in such scarcity, that when an uncle’s family emigrated to Nordamerika in 1869, young John and Gustav dreamed of following? After their mother died at age 54, “we could go without giving her sorrow,” so the brothers made their way to Göteborg — “by far the farthest from home we had ever been.” On the morning of June 12, 1876, they boarded the steamer Orlando for England, from where they would sail to a new life in a faraway country they’d never seen.

They were far from alone in making that journey: Between the mid-1840s and 1930, almost 1.3 million Swedes immigrated to America. If your ancestors were among them, our seven-step plan will give you a taste of family history success.

Past achievements

The first Swedes arrived in America just 18 years after the Mayflower, establishing a colony, New Sweden, in what’s now Delaware. But the great wave of Swedish emigration wouldn’t begin until after America’s Civil War with a population explosion in Sweden’s primitive agricultural society, which offered scant opportunity to people like my ancestors. As Swedish bishop and poet Esaias Tegnér famously put it, “peace, vaccination and potatoes” caused the population in some parishes to triple. With no wars since 1814, declining infant mortality thanks to smallpox immunization, and the dietary addition of potatoes, Sweden’s population doubled between 1750 and 1850. A series of crop failures in 1867 (“the wet year” when grain rotted) and 1868 (“the dry year” when fields burned), followed by “the severe year” of epidemics in 1869, sparked an exodus. By 1910, the United States was home to some 1.4 million first- and second-generation Swedes — almost one in five of the world’s Swedish population. Their ancestral country ranks behind only the British Isles and neighboring Norway in the proportion of its population crossing the pond.

Like my ancestors, many emigrants settled in Illinois — at the time, more Swedes lived in Chicago than in any other city except Stockholm. The Homestead Act drew others to Minnesota, where railroad tycoon James J. Hill enlisted them to lay tracks across America: “Give me snuff, whiskey and Swedes,” Hill declared, “and I will build a railroad to hell.” Others went all the way to the Pacific Northwest. Today, the states with the largest populations of Swedish descent are Minnesota, California, Illinois, Washington and Michigan.

At least 4 million Americans trace some or all of their ancestry to Sweden. Those have included aviator Charles Lindbergh, astronaut Buzz Aldrin, former Supreme Court Chief Justice William Rehnquist, actress Greta Garbo, ventriloquist Edgar Bergen and his daughter Candice, and author Ray Bradbury. Oh, and if you study geology, you’ll likely come across John Fryxell’s son Fritiof, who helped establish Grand Teton National Park.

Family history feats

If you’re not lucky enough to have a biography of your Swedish immigrant ancestors, you still can learn about their lives and trace their paths back across the Atlantic. Once you’ve placed them in a parish (socken) there, you can take advantage of Swedish church records, which are among the world’s most thorough genealogical resources. That’s in part because the Lutheran church, the official state church from the 1500s until 2000, required ministers to maintain kyrkoböcker — church vital records — for everyone in their parish, regardless of their faith. “Dissenter” churches weren’t allowed to keep their own records until 1915. A high percentage of these documents survive because Sweden was largely spared the wars that destroyed other European records. I’ve been able to trace several branches of my family tree to the mid-1650s, and you can enjoy similar genealogical success with these seven steps to finding your Swedish ancestors:

1. Explore sources at home. The more you can narrow your search, the less you’ll be poring over page after page of old handwriting. Before getting started, you must discover your ancestor’s last parish of residence in Sweden; you also should try to learn at least his year of birth. “Look in the attic for obituaries, old photos with at least the photographer’s name on them, old books with Swedish writings (hymnals, Bibles, etc.), and whatever can be found,” advises Elisabeth Thorsell, editor of the Swedish-American Genealogist. If Swedish letters or documents stump you, see page 55 for language hints.

Quiz your relatives, too. When stuck on a branch of my great-grandmother’s family, I kept pestering my second cousin. Finally, tiring of my questions, she replied, “Maybe I should just send you the family Bible.” I almost dropped the phone. She had the mammoth old book, filled with ornate Gothic script, that our great-grandfather Oscar Lundeen had brought over on the boat from Sweden. I quickly agreed that yes, sending the Bible would be a fine idea.

2. Check church records stateside. Many Swedish-American churches kept records as meticulous as the ones back home. The Swenson Swedish Immigration Research Center <www.augustana.edu/swenson/genealogy.html> at Augustana College in Rock Island, Ill., has an outstanding collection of such records, including those of Augustana Lutheran, Mission Covenant, Evangelical Free, Swedish Methodist, Swedish Baptist and Swedish Episcopal churches. Besides information such as date of confirmation and date and place of birth and baptism, you may find your ancestor’s year of arrival in America and places he lived here. You can request a search by a staff member for $30 per hour, or research in person for a $10-per-day nonmember fee.

3. Win the name game.Don’t assume your family’s name here in America was the same back in Sweden. John Fryxell, born Sven Johan Magnusson, chose his new surname for his stint in the Swedish army. So many soldiers had the same last name — something ending in -son — that they had to pick an “army name” for their mandatory military hitch. John took Fryxell, a name whose pronunciation so helpfully befuddles phone solicitors (it’s frick-SELL), from a Swedish poet and historian he admired. When he and Gustav arrived in America, John later recalled, “the customs officials told us it was not advisable for two brothers to have different names,” so today, we’re all Fryxells.

Again, ask your relatives. When I told my aunt I was stumped on the Lundeens, she responded, “Didn’t you know? They were Ingelssons back in Sweden.” Sure enough, seven of the siblings were Ingelssons, three somehow became Lundeens and one inexplicably was a Blomberg.

The name confusion continues back in Sweden, where last names could change with every generation until permanent surnames became official in 1901. Under the country’s patronymic system, a child took his last name from the father’s first name. So Magnus’ son became Magnusson and his daughter was Magnusdotter. Although this makes it difficult to trace families by surname, it does give you the father’s first name. Patronymics weren’t universal, though. My great-grandmother, for example, was christened Maria Ekström, with the surname of her father, Olof Ekström. On the plus side, you can say goodbye to the genealogist’s maiden-name dilemma: Records usually refer to women by their maiden names, even after marriage.

4. Explore immigration and emigration records. Many Swedes arrived in America prior to the 1892 opening of Ellis Island <ellisisland.org>, so you may find New York passengers in the online database of arrivals at Ellis Island’s precursor, Castle Garden <castlegarden.org>. Also look for early immigrants in Swedish Passenger Arrivals in the United States, 1820-1850 (Swedish American Historical Society). Keep in mind that, like my Fryxell ancestors, emigrants rarely sailed directly from Sweden to America. They typically departed from Göteborg, Sweden’s second-largest city, to the port of Hull in England, then traveled by train to Liverpool or Glasgow, and connected with a vessel bound for New York City.

If you strike out with US immigration resources, try looking in Swedish emigration records. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ Family History Library (FHL) <www.familysearch.org> in Salt Lake City has microfilmed records of emigrants through the port of Göteborg (1869 to 1920), plus an index to passports issued in Göteborg (1680 to 1890). Emigrants via Stockholm (1851 to 1940) are on FHL microfilm of Emigrantlistor, the police department’s passenger-list information. You can borrow microfilm from the FHL through branch Family History Centers (FHCs). Use FamilySearch to find one near you.

Two pricey — but worth it, if you’ve hit a brick wall — CDs can make searching Swedish emigration records a snap. Emigranten/The Swedish Emigrant (two-disc set, $190, <www.goteborgs-emigranten.com>) contains the Emihamn database of approximately 1.3 million emigrants from the major Swedish ports Göteborg (1869 to 1930), Malmö (1874 to 1930), Stockholm (1869 to 1930), Norrköping (1859 to 1919), Helsingborg (1899 to 1930) and Kalmar (1880 to 1893). The database, drawn from police archives, includes the person’s name, relationship to other passengers, sometimes an occupation, age at emigration, birthplace or place of residence, county, destination and date of emigration. The set also includes a database of 242,000 Swedish American Line passengers (1915 to 1950), extracts from passport and emigrant lists (1817 to 1860), and other goodies.

Data on the Emibas CD ($96 from <genlineshop.com>) come from church records — yes, parishes also tracked citizens’ comings (inflyttningslängd) and goings (utflyttningslängd) — and cover 1.1 million emigrants from more than 2,300 parishes, roughly three-quarters of all departures between 1845 and 1930. The records contain the person’s name, title or occupation, sex, birth date, birth parish, marital status, place of residence, date of emigration and destination.

Because you can search these CDs by several parameters, they often can crack mysteries insoluble by brute-force page-turning. For instance, if you can’t figure out the Swedish surname or parish, but know your ancestor Oscar (or perhaps Oskar?) was born in March 1852, and wasn’t married when he emigrated, enter these criteria in Emibas — using a wildcard (*) for the name, as in Os*ar. You’ll get just 17 matches. Emigranten lets you search for everyone who left a particular parish in a given year or, for example, everyone named Oscar who was headed to Moline, Ill.

Located in the Baltic Sea, Gotland island — part of the region where the Goths originated — is famous for its medieval city Visby.

St. Mary is one of the island’s 92 churches dating between 1150 and 1400.

5. Get the place right.Sweden is divided into 25 provinces dating from medieval times, which no longer serve any administrative purpose. It’s also carved into 21 counties whose borders were established in 1634 but have changed several times since. Though most Swedes identify with their province, records are grouped by county, and within each county, by parish. Swedish counties also are divided into municipalities, but you want the parish because that’s the key to church records.

Even once you’ve gathered some clues, you may need a hand connecting them with the correct name and location of your ancestor’s parish in Sweden. The Genealogical Guidebook & Atlas of Sweden by Finn A. Thomsen (Thomsen’s) contains an alphabetical list of parishes by county, along with basic maps. At Land-survey <www.lantmateriet.com>, you can browse and even customize both current and historical maps. The National Atlas of Sweden <www.sna.se/e_index.html> and its searchable Swedish Gazetteer <www.sna.se/gazetteer.html> can help unscramble parishes and place names.

That family Bible I lucked upon gave me the missing birth parish of Oscar Lundeen’s wife, Maria Ekström — if only I could decipher it. In the squiggly old handwriting, it looked like Harvard, but I knew that couldn’t be right. I searched the Swedish gazetteer using wild cards (* for any number of characters and ? for a single character) and finally hit upon the parish of Hackvad.

6. Go to church records. In the 1950s, the FHL microfilmed more than 100 million pages of these church records — 61,000 rolls of film. Once I’d identified Maria’s original parish, I started borrowing Hackvad microfilm through my local FHC. After some scrolling, I found my great-grandmother Maria, age 7, in an 1863 household inventory with her father, Olof Ekström, and her mother, Anna Maja Pehrsdotter. Suddenly, the puzzle of this family branch began to come together.

The bishop of Västerås set the first rules for record-keeping in his diocese in 1622. But generally, church records begin after the 1686 decree requiring all parishes to maintain records of:

• Persons receiving communion, later supplanted by the far more useful household examination record (hus-förhörslängd) — the lists that led me to Maria’s family. Available for most parishes beginning in the late 1700s, these household inventories are your main tool for tracing relatives, year by year, back in time. Most list each family member, including children, along with dates and places of birth, occupations, dates of marriage and death, notes on children’s legitimacy, and information on anyone who left or moved within the parish during the years covered by each sheet.

• Birth (födde), including names of parents, christening witnesses, birth and christening dates, and the child’s name and place of birth

• Marriage (vigde), including the names and residences of the couples and names of their parents

• Death (döde), including age at death, burial place, last residence and occupation

Use the latter three records, located on the same microfilm rolls as household inventories, to fill in any blanks. Once you know an ancestor’s birth date, you’ll speed your browsing through these handwritten pages. That’s because Swedish church records use the birth date as a sort of identifier — helpful when a parish has a dozen Anders Jonssons — and the last two digits of the birth year usually are written larger. So you can quickly find your Anders Jons-son, born in 1859, by looking for names with a big 59. Keep in mind that Swedes flip-flop month and year compared to US usage, so 1859 10/3 is March 10, 1859.

If you hate scrolling microfilm — or waiting for it to arrive — you’re in luck: Genline <genline.com> has digitized almost all Swedish church records, nearly 16 million images at last count. At roughly $370 a year, it’s not cheap, but Genline is always running specials and offers a variety of introductory deals. See our review of the site in the June 2005 Family Tree Magazine.

A new Web site from SVAR (Svensk Arkivinformation) <www.svar.ra.se>, a division of the Swedish National Archives, also has digitized church records. The collection doesn’t yet match Genline’s, but more parishes are added every month, and a subscription ($165 a year, $41 for 10 three-hour visits) also gives you access to the 1890 and 1900 Swedish censuses (plus scattered 1860, 1870 and 1880 records); limited indexes of births, marriages and deaths; and a database of seamen. If you’re still searching for your ancestral parish and have a farm name for a clue, SVAR’s village and farm database alone may be worth the $7 price of a three-hour tour. See the June 2006 Family Tree Magazine for a review of the SVAR site.

Other, more geographically limited online sources of parish records include the subscription Web site Indiko <www.ddb.umu.se/windiko/windikoeng/indikohuvudsidaeng.htm>, about $14 a month plus a $14 setup fee, and the free Demographical Database for Southern Sweden <ddss.nu/engelsk>. FamilySearch includes a vital-records index for Scandinavia with birth, christening and marriage information extracted from church records in selected parishes. You also can search more than 1.5 million volunteer-extracted vital records at <proband.slaktdata.org/search> (as of press time, this site was available only in Swedish).

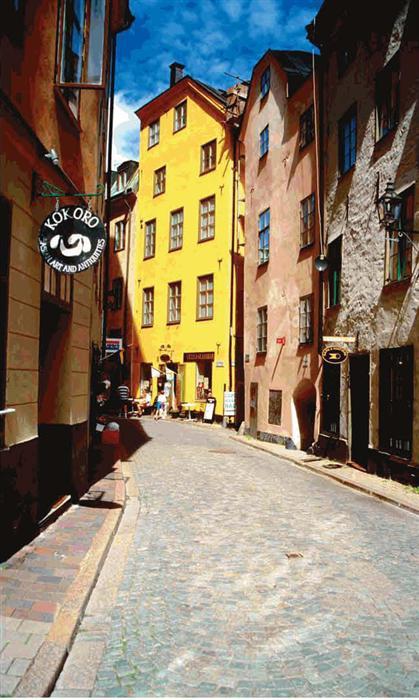

Gamla Stan(which translates to “old town”) is the earliest part of Stockholm.

7. Expand to other records. Even though church records are the Swedish researcher’s pot of gold, they’re not the end of the story. “To flesh out the life of a person,” Thorsell says, “check probates and tax rolls (mantalslängder). If there’s a note that someone has to pay a fine for something, there are very detailed court records. If someone was a soldier, there are fairly detailed military records.” The FHL has microfilmed some Swedish directories and military records, as well as many probate records. A place search of the online catalog on the name of your ancestral town or county should turn up these records.

You can find censuses, dating to 1620 in central Sweden, in the FHL online catalog by running a place search of the county (län) name. The 1890 census is available online from SVAR; records for Norrbotten, Västerbotten, Västernorrland, Jämt-land and Värmland counties are free online <www.foark.umu.se/census>. You can purchase the whole census on the Swedish Census 1890 CD ($86 from <genlineshop.com>). Remember most Swedish immigrants had already come to America by 1890, so this census is handy primarily for the folks who stayed behind.

Joint efforts

There’s just one problem with the genealogical riches awaiting you in Swedish church records — they’re in Swedish. Written Scandinavian languages employ characters beyond our familiar 26. In Swedish, you’ll see the letters Å, Ä and Ö, which are usually alphabetized after Z. For translation aid, try the online Swedish-English dictionary <www-lexikon.nada.kth.se/skolverket/swe-eng.shtml> and genealogy word list at <slaktdata.org/en/lexicon>. FamilySearch also has a free online guide to Swedish words commonly used in genealogy, under Search>Research Helps (click S and scroll down the page). Thorsell suggests investing in the Swedish Genealogical Dictionary and posting a call for help on Anbytar forum <genealogi.aland.net/discus>.

In fact, you’ll be pleasantly surprised at how many genealogists in Sweden can help you — in English, over the Internet — when you hit a dead end. Founded in 1980, the Computer Genealogy Society of Sweden is the world’s oldest such organization and boasts almost 23,000 members. Its DISBYT database <www.dis.se/denindex.htm> contains 10.7 million member-submitted records. Searching is free (follow the instructions on the page, then use the search link on the left), but a $15 annual membership gets you access to more in-depth results. The society’s new DISPOS service will even help you figure out where your ancestors’ records are located.

Besides the Anbytarforum message boards, the Federation of Swedish Genealogical Societies offers English-language assistance at <www.genealogi.se/roots>. SweGGate (Swedish Genealogy Gate) <rootsweb.com/~swewgw> is Sweden’s WorldGenWeb Project site. Thorsell also offers suggestions on her Web site <www.etgenealogy.se/english.htm>.

Your Swedish ancestors, like mine, probably endured a lot to bring their hopes and dreams to Nordamerika. With these steps and a little luck, it won’t be too hard to find success retracing their route.

Timeline

Toolkit

Web sites

• Computer Genealogy Society of Sweden

• Demographical Database for Southern Sweden

• ET Genealogy

<www.etgenealogy.se/english.htm>

• Genline

• FamilySearch: Vital Records Index for Scandinavia

<www.familysearch.org>: Click Search, then Vital Records Index, and select Sweden.

• Föreningen Släktdata

• Indiko

<www.ddb.umu.se/windiko/windikoeng/indikohuvudsidaeng.htm>

• Landsurvey

• National Atlas of Sweden

• Swedish-English Dictionary

<www-lexikon.nada.kth.se/skolverket/swe-eng.shtml>

• Swedish Gazetteer

• SweGGate

Books and CDs

• 24 Famous Swedish Americans and their Ancestors compiled by Sveriges Släktforskarförbund (Federation of Swedish Genealogical Societies)

• Cradled in Sweden by Carl-Erik Johansson (Everton Publishers)

• Emibas CD (Swedish Emigrant Institute)

• Gamla Stan CD (Stockholm City Archives)

• The Genealogical Guidebook & Atlas of Sweden by Finn A. Thomsen (Thomsen’s)

• Kungsholmen CD (Stockholm City Archives)

• Swedish American Genealogist ($25 annual subscription from <www.augustana.edu/swenson/sag.html>)

• Swedish Census 1890 CD (Arkion/Federation of Swedish Genealogical Societies)

• Swedish Deaths 1947-2003 CD (Federation of Swedish Genealogical Societies)

• The Swedish Emigrant CD (Swedish Emigrant Institute)

• Swedish Genealogical Dictionary (Pladsen Sveria Press, )

• Swedish Passenger Arrivals in New York, 1820-1850 by Nils William Olsson (Swedish American Historical Society, out of print)

• Swedish Passenger Arrivals in US Ports, 1820-1850 (Except New York) by Nils William Olsson (North Central Publishing, out of print)

• Swedish Passenger Arrivals in the United States 1820-1850 by Nils William Olsson and Erik Wikén (Schmidts Boktryckeri AB, <www.swedishamericanhist.org/booklist.html>)

• Your Swedish Roots by Per Clemensson and Kjell Andersson (Ancestry)

Organizations

• American Swedish Historical Museum

1900 Pattison Ave., Philadelphia, PA 19145, (215) 389-1776, <www.americanswedish.org>

• American Swedish Institute

2600 Park Ave. S., Minneapolis, MN 55407, (612) 871-4907, <www.americanswedishinst.org>

• Federation of Swedish Genealogical Societies(Sveriges Släktforskarforbund)

Allen 7,172 66 Sundbyberg, Sweden, +46 (8) 440 75 50, <www.genealogi.se/roots>

• Genealogical Society of Sweden

Allen 7-9,172 66 Sundyberg, Sweden, +46 (8) 32 96 80, <www.genealogi.net>

• Göteborg Emigranten

Box 53066,40014 Göteborg, Sweden, +46 (31) 18 00 62, <www.goteborgs-emigranten.com>

• Kinship Center

Box 331, S-651 08 Karlstad, Sweden, +46 (54) 617726, <www.emigrantregistret.s.se/frameset-en.htm>

• Swedish American Historical Society

3225 W. Foster Ave., Box 48, Chicago, IL 60625, (773) 583-5722, <www.swedishamericanhist.org>

• Swedish Ancestry Research Association

Box 70603, Worcester, MA 01607, <sarassociation.tripod.com>

• Swedish Emigrant Institute

Vilhelm Mobergs Gata 4, Box 201, SE 351 04 Växjö, Sweden, +46 (470) 20120, <www.swemi.nu/eng>

• Swedish National Archives — Marieburg

Box 12541, SE-102 29 Stockholm, Sweden, +46 (8) 737 63 50, <www.ra.se/en>

• Swedish National Archives — Military Archives

SE-115 88 Stockholm, Sweden, +46 (8) 782 41 00, <www.ra.se/kra/english.html>

• Swenson Swedish Immigration Research Center

639 38th St., Rock Island, IL 61201, (309) 794-7204, <www.augustana.edu/swenson/genealogy.html>

• SVAR research center

ADVERTISEMENT