Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

When William D. Gallager made his will on March 27, 1869, in Hamilton County, Ohio, the sixth item stipulated that $100 of his estate should go for the upkeep of his mother’s grave. He further commented in his will that “when in Philadelphia I tried but in vain to find the remains of my father to have it removed with my mother in New Castle, Del., but the heathens had sold his house to build a big church. This they call Christianity. Heathens would not do so.”

Sally Grymes made her will on Feb. 17, 1827, in Orange County, Va. She confessed that “as to my sons John Randolph and Thomas Nelson Grymes, I have nothing worthy of their acceptance after providing for my helpless daughters.”

While you might cringe at the thought of plowing through dry, intimidating legal documents, finding your ancestor’s will can bring a smile to your face and some vivid color to your family history. Sure, there’s that mumbo-jumbo legalese you wonder if even lawyers really understand. But once you get beyond the “sound mind and body” and the “I set my hand and seal” parts, you’ll find some fun and interesting aspects about your ancestors in wills, giving you a rare glimpse of their personalities — not to mention fascinating facts for your family tree.

What’s in a will?

Simply put, a will is a legal document providing for the distribution of a person’s property after he or she dies. The person making the will is known as the “testator.”Some wills are merely a page or less in length; others may be several pages long and go into unusual detail about instructions to be carried out after death.

There are several types of wills, but three are most common: An “attested will” is drafted by another party, such as a lawyer, for the testator. A “holographic will” is one that the testator writes, dates and signs in his or her own handwriting. A “nuncupative will” is one that’s dictated orally by the testator, usually on his or her deathbed. This type of will must be written out within a short time period, and it may not be valid in some jurisdictions.

Genealogists love finding ancestors’ wills because they usually state family relationships — but wills don’t always give names. You may find a man leaving items to his “beloved wife” (I’ve yet to see one say, “to my nagging wife”) with no mention of her name. Why should there be? Everyone knew who she was. On rare occasions a husband will name his wife and give her maiden name in a will, stating, “to my beloved wife, Mary, formerly Mary Rogers.” More likely, though, you’ll find wills that merely say, “to my beloved wife, Sophia,” or simply, “my wife.” If you see “my now wife,” this simply referred to the woman to whom he was married when he made out the will; it’s not necessarily an indication that he’d been married before.

Wills often mention names of the testator’s children; conversely, I’ve seen wills that give the names of barn animals, but not the names of the children. So these records can be frustrating at times. Married daughters are usually mentioned by their married names, and sometimes the husband’s name will also be included: “to my daughter Mary Williamson, wife of John Williamson.” Or you might find, “to my granddaughter, Polly, daughter of my late son Isaac.” Those are the kinds of wills you hope for — you now have three generations named within one document.

Occasionally you’ll find a will that omits more than a name — a child you know existed might be missing entirely. This can happen for several reasons. The parent could have already transferred property to that child, such as when a daughter or son married. The child might have died before the will was created, or been born after the parent’s death. It’s also possible the child was disowned. If that’s the case, though, the will should state this omission so the disinherited offspring doesn’t contest the will later. Wills and probate records may reveal the testator’s place of origin, or they may name relatives in the old country. Many immigrants — the Irish in particular — were likely to leave bequests to relatives back home, naming the hometown. For example, Thomas Major, a merchant in New York, made his will on Oct. 18, 1800. In it, he directed that if he should not have any children by his present wife, then after her death, he would give to “the child or children of my sister Mary Cupples of Killyree, County of Antrim and Kingdom of Ireland, the residue of my estate….”

Although a will typically doesn’t give the person’s date of death, it does help you narrow down the time frame. For example, Townshend Dade made his will on April 9, 1761, and it was entered into the Stafford County, Va., probate court on June 9, 1761; so we can say that he died between April 9 and June 9, 1761. This is why it’s important to take note of both dates. Once in a while, you’ll find the death date mentioned with the date the will was admitted into probate.

Now that you know what goodies these legal documents can contain, how do you find your ancestor’s will? Before you head out the door hunting for wills, it’s helpful to know exactly what you’re looking for and some terminology.

Understanding the Probate Process

Wills enter into a court process known as probate, which oversees the transfer of the deceased’s property and possessions to heirs. When a person dies leaving a valid will, that person is said to have died “testate.” When a person dies leaving no valid will, he or she is said to have died “intestate.”

Not everyone left a will, and not all wills were recorded. Wills are usually probated in the court that has jurisdiction where the person resided at death.

Here’s a simplified look at the probate process:

- A person makes a will.

- The person dies.

- An interested parly, usually an heir, presents the will to the probate court.

- The court admits the will to probate.

- The will is recorded.

- The executor (the person named in the will who will sec that it gets carried out; it’s the executrix if the named person is female) usually makes an inventory of the deceased’s estate. Other items in the process may include a notice to hen’s of accounts, distributions and sale of property.

- The provisions of the will are carried out after all debts are paid.

Intestate probate process

If a person died intestate, the heirs may enter the deceased’s estate into probate, assuming the person left an estate of sufficient worth. This worth depends on each state’s laws. You may find intestate cases recorded in a separate volume from wills, or they might be included in the will books. In an intestate case, the probate process is slightly different:

- The person dies.

- Someone with an interest in the estate petitions the probate court, seeking what’s known as letters of administration.

- The court appoints an administrator (administratrix if a woman is appointed), who assumes essentially the same tasks as an executor or executrix.

- The administrator makes an inventory of the estate.

- The administrator makes a list of heirs, including their present residences.

- After debts have been paid, the remaining estate is divided among the heirs according to state laws.

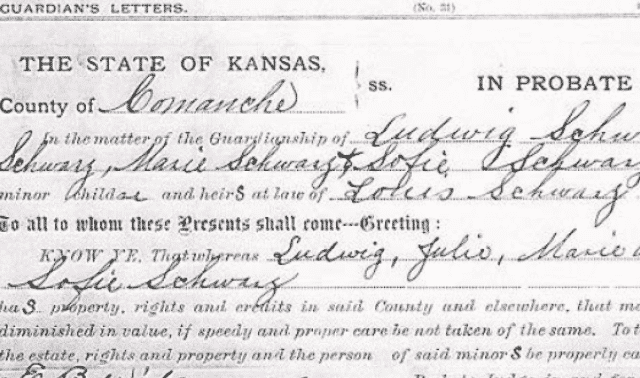

When you find a will in a clerk’s will book, you’re looking at the recorded will, not the original. Ask if the “probate packet” still exists, as this should contain all the surviving documents generated during the probate process, including the original will. Contested wills and records are kept in the court of the original probate, usually within this packet. If the original will still exists, make sure to check it because errors could have been made when the clerk hand-copied it into the will book. Sometimes the recorded will is all that’s survived.

Also check the local newspaper around the time your ancestor died. You may find a notice asking interested parties to come forward in an attempt to settle the estate.

Making Abstracts of Wills

While you’ll want to make a photocopy of your ancestor’s will when you find it, abstracting the record for later use is easier than reading through the whole document again. Here are the key items to record when abstracting a will:

- type of record (will, inventory, intestate proceedings, etc.)

- source citation (book, page/s, file number, microfilm number)

- repository name and address

- name of testator (person making the will)

- personal information (“of sound mind and body,” desired burial, etc.)

- names and relationships (if given) of executors

- date the will was signed

- date the will was entered into probate and/or recorded

- signature or mark of testator

- names and addresses (if given) of witnesses

- bequests and devises (names, relationships, items each person is to receive, including land descriptions)

Inventories of estates

Within the probate packet, or recorded in the will books or separate volumes, you might find an inventory of your ancestor’s estate, which will detail the deceased’s belongings and assign a monetary value to them. From an inventory, you can figuratively follow the executor or administrator from room to room in the person’s house. Here’s a small sampling from an inventory of Mary Clark’s household belongings in Greenwich, Conn., from a 1908 probate record:

| North Bed-Room Carpet | $.25 |

| Bedstead | $2.00 |

| 3 Mattresses | $2.50 |

| 1 Bed Spring | $.50 |

| 2 Pair Curtains | $.50 |

| Feather Bed | $.05 |

| Bed Spread & Bolsters | $2.00 |

| Steamer Chair | $.40 |

| Low Chair | $.25 |

| Bureau | $.25 |

| Wash-stand | $.75 |

| Lantern | $.20 |

| Trunk | $.75 |

| 7 Pictures | $.75 |

| 1 Glass | $.25 |

| 2 Frames | $.20 |

| Small Box | $.10 |

Also look for the list of outstanding bills to be paid out of the estate. Some of these list doctors’ fees, payment for making the coffin and other assorted expenses the deceased incurred before and after death.

Finding wills in the courthouse

Probate packets and wills recorded in will books are held at the county courthouse, unless the records have been transferred to a state archive. Not all states call their probate courts the same thing. The jurisdiction that recorded your ancestor’s will might be called the superior court, a circuit court, a district court, a chancery court, a register of wills or a surrogate’s court. Check The Handybook for Genealogists (Everton Publishers) or Ancestry’s Red Book (Ancestry) for county courthouse addresses and the name of the appropriate jurisdiction. Probate records are usually indexed; they’ll be listed by the name of the testator or intestate person, not by the people named in the will.

Here are some quick tips for finding your ancestors’ wills:

Working from the date your ancestor died, check microfilmed indexes of wills through the Family History Library in Salt Lake City, Utah. You can access the library’s catalog online at FamilySearch.org. Look under the county and state your ancestor last resided or died in, then under “probate records.” You’ll get a list of the resources available on microfilm.

Sometimes the library has the index to probate records, but the actual records haven’t been filmed. Even so, searching the index yourself is always better than relying on a clerk who may not check for other relatives or under variant spellings.

If the FHL doesn’t have a microfilmed index for the time period your ancestor died, you can still write directly to the probate clerk and ask if your ancestor left a will. Give your ancestor’s full name, date of death and any other identifying information. Don’t forget to include a self-addressed, stamped envelope so the clerk can tell you if the record is there and what the fee will be to obtain a copy. Remember, too, to ask if the entire probate packet still exists and how much it would cost to copy it.

Another useful resource is an abstract of wills. Kindhearted genealogists make will abstracts available to the rest of us by reading every single will in a will book, then publishing a summary of the important aspects of a document, leaving out all the legal mumbojumbo. You might find published abstracts for your ancestor’s area in a genealogical library, or check with a specialty genealogy publisher such as Heritage Books. Some abstracts and indexes are also popping up online; try a search engine such as Google to see what’s available for your state. Abstracts are wonderful starting points, but you should always then seek the original will or the recorded copy of the original in the courthouse. As wonderful as abstracters are, after all, they’re only human and do make mistakes.

Seeking slaves in wills

Family members aren’t the only people you can find named in wills. Slaves, for example, were often named in the will of the white slave owner. But it’s extremely important to learn the state laws of inheritance during a given time period — specifically, you’ll need to find out whether slaves were considered real property (attached to the land, crops or buildings, as in “real estate”) or personal property. For example, in Maryland and South Carolina, slaves were considered personal property; in Virginia in 1705, the law was changed to make slaves real property for purposes of inheritance. When slaves were considered personal property, they were more likely to be passed along to daughters; when slaves were deemed real property, they probably went to the sons who inherited land.

If the owner didn’t leave a will, tracing the inheritance of slaves can get complicated. The slaves may have become the property of the widow or may have been distributed to other heirs. The widow might have gained absolute title, meaning she could bequeath them to anyone she wanted at her death, or just a life interest, which terminated upon her death. And what happened if the widow remarried and then died? Did the slaves go to the second husband and his heirs, or to her heirs from her first marriage? You’ll have to study the state’s laws of inheritance during that period to determine the direction your research should take.

Here’s an example of a will from Stafford County, Va., in the mid-18th century. See how it stated who was to inherit which slaves:

First I give to my Daughter Elizabeth Washington Dinah Virgin & their increase which she has in her possession, to her. & her assigns forever. Secondly I give to my Grandson Langhorn Dade one negro man named Juba. Thirdly I give to my son Baldwin Dade, two negro men called Solomon & George — Fourthly I give to Sarah Dade widow of Cadwallador Dade two negroes lien & Sukey. Fifthly I give to my Daughter Frances Stuart the following Negroes Jem. Kate. Nancy. & their increase. which she has in her possession. Sixthly. I give to my son Horatio Dade the Following — negroes Harry Jolly. Daniel. Moses. Nan & her increase….

Note the language “and their increase” after female slaves are mentioned — this means the slave woman’s children. Also notice the lack of punctuation: “I give to my Daughter Elizabeth Washington Dinah Virgin & their increase….” Is the daughter’s name just Elizabeth, and the slaves she’s inheriting are Washington and Dinah and Virgin? Or is the daughter’s name Elizabeth Washington, and she’s receiving two slaves, Dinah and Virgin? Obviously, further research about Elizabeth will be needed to answer the question.

Women in wills

The treatment of women in wills is also worth noting. For example, let’s look at the will left by James Madison Fitzhugh dated May 8, 1844, and recorded March 24, 1845, in Orange County, Va. He bequeathed his whole estate, real and personal, to his wife, Mary F. Fitzhugh. He also gave her the power to dispose of any of his property that she thought best, provided she did not marry. James stipulated in his will that if she did remarry, she would forfeit all of his property, which would then be equally divided among his (unnamed) children.

You might think James was the jealous type and couldn’t bear the thought of his wife marrying again after his death. Actually, this was his way of ensuring that his property would stay in his family line. When a woman married, all of her property became her husband’s, so this second husband would then own the first husband’s property, and hubby number two could dispose of it as he wanted or pass it on to his own heirs. James wanted to ensure that this wouldn’t happen and that his children — not a second husband — would get his property.

James further stated in his will that “If my wife should marry and demand her thirds, at her death, this portion of my estate I desire to be equally divided between my children forever.” James was acknowledging that, by law, Mary was entitled to her dower rights (known as the widow’s thirds). Dower rights were a provision in the law so that a widow would not be left destitute. Even if there was no will, the widow was still entitled to one-third of her deceased husband’s estate. In the Fitzhugh case, if Mary married again, she had a right to demand her one-third portion of James’ property, but it was only a life interest (for the term of her life). After she died, the property would go to James’ children instead of any children Mary might have by a second marriage.

Feeling the need to call a lawyer yet? Don’t worry — you don’t have to pass the bar to understand some of the legal documents your ancestors created. Family historians just like you have learned how to read and interpret wills and probate records. In the process, they’ve discovered these documents are some of the most interesting that you’ll come across.

In fact, the biggest problem with wills is not finding one. Too often, your ancestors didn’t leave a will or their estate wasn’t of sufficient value to be entered into probate. But never assume that’s the situation and never give up. Always check to see if a will or intestate case was recorded for every one of your ancestors. Where there’s a will, there’s a way to find it.

A version of this article appeared in the October 2001 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

ADVERTISEMENT