Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

The government can make or break your genealogy research. Laws that created records about your ancestors, like the Census Act of 1790 (which facilitated the first US censuses) and the Steerage Act of 1819 (which mandated passenger arrival lists), are boons to genealogists across the country.

The resulting documents were stored (and sometimes, lost) in government custody. Tax dollars and government grants allowed them to be microfilmed or digitized. And lawmakers and agencies set policies that determine if and how you can get a hold of records—plus how much it will cost you to do so.

There’s no doubt that federal, state, county and town governments play an important part in your genealogy search. They’re responsible for many of the records you rely on to fill out your family tree.

And do you have a place in all these policies and processes? Why yes, you do. We’ll explain the government’s role in your genealogy and how you can have a say in it.

Genealogy Records Created by the Government

Many of the most-used genealogy records exist in the first place because local, state and federal governments passed laws and set policies that required them to be created.

“Our ancestors interacted with the government all the time—to be counted in the census, for building permits, immigration visas, passports, voting, buying property,” says Rich Venezia, a Pennsylvania-based professional genealogist who runs the research firm Rich Roots and is a founder of the Records, Not Revenue advocacy campaign. “Not only are these records genealogically significant, but they can really color in the details of our ancestors’ lives.”

Laws established what records had to be kept, what details they would include, and which government office would keep the document. Those laws leave us with genealogically informative sources like:

State vital records

In the United States (which has never had a national civil registration system), states, counties and municipalities recorded vital events. New England towns were the first US entities to keep birth and death records in register books, starting as early as the 1600s. (Unfortunately, many towns’ registries have gaps for which records were lost or births and deaths were missed.)

Some large cities (as well as many states) made it mandatory to record births and deaths in the 1800s. But it wasn’t until the early 1900s that all states had passed vital records laws, which usually require counties to keep the records and forward copies to the state.

Marriage licenses and returns

County courts or town clerks usually kept marriage records as soon as the counties were formed.

Court records

Courts at the county, state or federal levels documented legal matters like deeds, wills, divorces, naturalizations, contracts, and criminal and civil cases.

Census records

The Constitution called for the first census (taken in 1790) to determine states’ representation in Congress, plus subsequent enumerations every 10 years. Federal census returns were open for public reading until 1879; the rule closing censuses for 72 years was passed in 1978. Various states have kept censuses as well, with their own privacy rules.

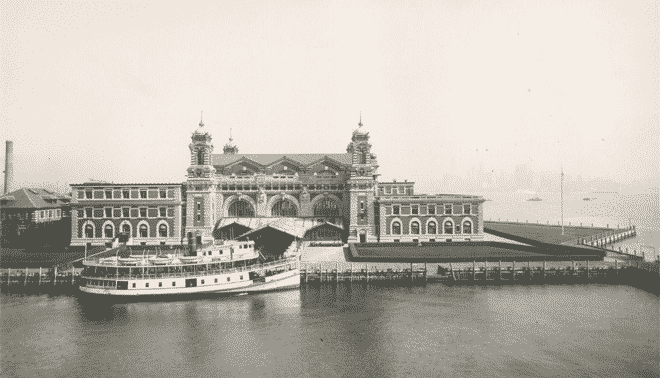

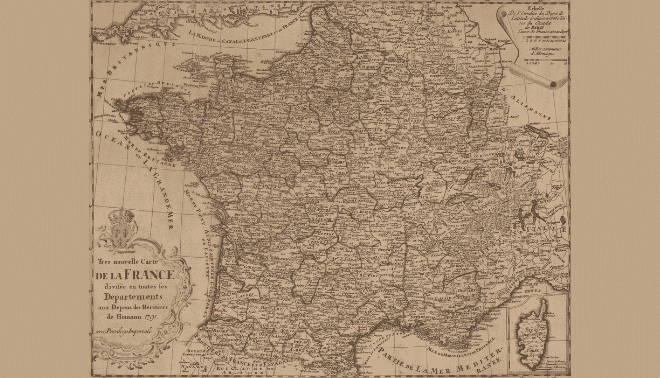

Immigration and naturalization records

In 1820, Congress required ships’ captains to record passengers’ names. After 1890, as laws required increasing information about travelers, ships’ manifests tell you even more about your immigrant ancestors. Naturalization declarations and certificates were standardized and centralized with the Naturalization Act of 1906. Before that, your ancestor could file for citizenship in any local, state or federal court.

Military records

Veterans or their surviving spouses and children filled out applications each time Congress passed laws making new groups eligible for pension benefits. In 1871, for example, War of 1812 veterans who served at least 60 days (or their widows) became eligible to apply for a pension. In 1878, veterans who served at least 14 days could apply.

One of the most-used military indexes, the 6-million-name Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Database, was assembled from cards that Department of the Army employees created from muster rolls to determine soldiers’ and sailors’ eligibility for pensions.

Land records

The Homestead Act of 1862 started a wave of federal land claim applications and patents that continued until 1988, when the last homestead applicant received title to 80 acres he’d claimed on Alaska’s Stony River. More than 1.6 million homesteaders took part in the program.

Other documents

Although these are the most common genealogy records with the broadest coverage, your ancestor might be named in lesser-known records as well. Did he get a license for his dog? Spend time in a county or state orphanage? Serve on a town’s zoning committee? Take out a loan from the Farm Security Administration during the Great Depression? All these government interactions generated records, and some of them might’ve survived for you to find.

All About Government Record Access

Government records are created using your taxes, and they reveal how public money is being used. That’s why part of the government’s job as records custodian is to provide you with access to records. Since 1967, the Freedom of Information Act has required the federal government to release certain records upon request. It allows exceptions, such as for documents that reveal trade secrets or matters of national defense. In 1974, the Privacy Act restricted records with personal, identifiable information about private citizens.

Later legislation clarified the fees agencies could charge to fill requests. For regular citizens, fees should be reasonable and go toward the staff’s search time (after the first two hours of work) and duplication of the records—in other words, Uncle Sam isn’t profiting off your FOIA request.

States have their own rules for records access. For example, according to Ohio’s Sunshine Laws 2024 manual, “Upon receiving a request for specific, existing public records, a public office must provide copies within a reasonable period of time. The public office may charge the requester the actual cost of copies made and may require payment in advance.” In Ohio, offices can only charge requestors for the cost of copying a record and delivering it to the requester (unless a law sets the cost). To learn the laws in your state, search online for the state name and sunshine laws.

And like the federal government, states also have exceptions to public records access. For example, vital records are usually restricted for privacy purposes—often, 25 or 50 years for death records and 75 or 100 for birth.

State access laws, in particular, are subject to change:

- Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker submitted a 2021 budget proposal that would have restricted birth and marriage records for 90 years, and death records for 50. (Previously, all records had been open to researchers.) The budget passed without that policy change.

- In 2022, advocacy group Reclaim the Records sued New York City, whose vital records are separate from (and more restrictive than) the rest of the state, to loosen the city’s lockdown on records. Partially as a result, the city created the NYC Historical Vital Records Project.

The government determines the form in which you access the records, too: paper, microfilm, or online in a searchable database. Local, state and federal budgets may set aside funds for providing access to records.

“Many counties across the country are putting certain records online, and it is such a boon for genealogy research,” says Venezia. “Here in Pennsylvania, some counties have digitized marriage licenses, naturalization records, and deeds, among other records.”

You can access some federal records through fee-based government programs like the US Citizenship and Information Services (USCIS) genealogy program. It lets you request records related to naturalizations, visas and resident aliens, including 5.5 million detail-rich alien registration forms completed during World War II.

Some old records, like passenger lists and censuses, have passed to the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). NARA, an agency independent of the federal government, holds records at research facilities around the country. Its most popular records also are available at other libraries on microfilm and/or digitized on websites like Ancestry.com and FamilySearch.

States usually send their old records to state archives and libraries, which may let you access them on microfilm or on library or commercial websites. In counties and towns, old records that survived might stay with the court or government department that created the record, or be sent to a library or historical society.

Government influence can even reach beyond public records to privately created ones. For example, the federally funded National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) offers grants for historical records preservation and access. One of its best-known programs among genealogists is the Chronicling America collection of digitized newspapers, which gets money from the NEH’s National Digital Newspaper Program. The newspapers are digitized and searchable on the Library of Congress website.

And public funding can be unpredictable:

- Federal budget proposals under the Trump administration allocated only enough money for the NEH to provide for the “orderly closure of the agency.” Fortunately, Congress passed final budgets with enough money for the agency to continue operating.

- The NARA facility in Seattle faced closure in 2020, with plans to ship its holdings to other NARA locations, hundreds of miles away in Riverside, Calif., and Kansas City. Federal courts and the Biden administration put those plans on indefinite hold after challenges from Indigenous tribes, historians and members of the general public.

- The USCIS announced in November 2019 that it was considering a massive fee hike for public requests of it genealogy records, the impetus for Venezia and other genealogists to start Records, Not Revenue. The rule ultimately wasn’t adopted after tens of thousands of user-submitted comments, and (in fact) a rule approved in January 2024 actually lowered record fees.

How to Advocate for Government Records

If the government is breaking (instead of making) your genealogy, you’re not alone. And you can join efforts to change access laws and other policies. Here are some ways how:

Stay informed

Follow local, state or national genealogical societies to learn about preserving and providing access to records of interest to you. For example, the Massachusetts Genealogical Council monitors activities of governmental agencies that affect genealogists and alerts the public of issues like Gov. Baker’s budget bill.

Venezia also recommends the International Association of Jewish Genealogical Societies, which has a public records access alert mailing list you can sign up for. You can share their calls to action on social media and (if you have the ability) donate to support their efforts.

You can also follow genealogy influencers on their blogs and social media accounts (such as Twitter and Facebook. Some of our suggestions include:

- Eastman’s Online Genealogy Newsletter

- The Legal Genealogist

- Reclaim the Records (@reclaimtherecs on Twitter)

Contact your elected officials

Venezia urges you to write and call your elected representatives with your opinions. Tell them you support funding for NARA, and for your state and local archives.

To find your representatives, search online for who is my representative and the place, or use Common Cause’s site or (for federal and state officials) USA.gov’s site.

Provide feedback on policy changes

Respond to calls for public comments on records-related issues. Federal agencies have a process that solicits feedback on proposed changes.

The Federal Register, the journal of the US government, typically reports such proposals. The Register issues a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking that includes an invitation to write, email or go online to make a comment.

The USCIS fee increase notice on the Federal Register attracted more than 12,000 published comments, due in part to the Records, Not Revenue campaign and other concerned genealogists. “Action is taken when many of us speak up,” Venezia says.

Visit Regulations.gov to see current notices and add your comments, and follow the Federal Register on Facebook (@fedregister) for updates. States have similar processes; to find your state’s register, visit StateScape.

The government’s role in your family tree research can’t be ignored. Your ability to understand your ancestors’ part in history—and how you came to be who you are—largely depends on the decisions of elected and appointed leaders regarding your family’s records. You have a say, and your say matters.

A version of this article appeared in the September/October 2020 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated in April 2024.

ADVERTISEMENT