Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

The road to discovering your ancestor’s past is often gated by the need to answer essential questions about his or her beginnings: When was he born? Where was her birthplace? Who were his parents?

The key to unlocking that gate often lies in birth records. This article will look at what you might find in a birth record, what types of records that exist for different places and time periods, and how to access the records. Because birth records aren’t always available, we’ll identify other resources you can utilize as alternatives.

Clues in Birth Records

Birth records are prized sources to genealogists because the informant was often a parent, doctor or other witness to the birth. As a result, a birth record generally contains primary (firsthand) information.

The two main types of US birth records are certificates and registers. A birth certificate, usually issued by the state, is a document naming an individual child. A birth register, frequently created by a city or county, lists many births occurring over a period of time. While both types of records tend to be trustworthy, registers are more prone to error because they may have been recorded later, when an informant reported the birth to a clerk.

In a typical birth record, you might find statements about:

- date of birth

- place of birth

- child’s sex and race

- child’s name

- mother’s first (and possibly maiden) name

- father’s name

- parents’ residence

- parents’ occupations

- parents’ ages and/or birthplaces

Not every record will include all of these details. And because any record can contain errors, you should compare what you find with other sources. A baptism record, draft card or death certificate might confirm a birth date. Sometimes these later records conflict with information in the birth record. In that case, look at all the evidence to determine which answer is best supported by reliable sources.

The clues in a birth record can boost your research in many ways. The date and place of birth can help you follow a family in census records. The birthplace gives you a location to dig for more information.

The golden nugget that keeps genealogists panning for birth records, though, is identifying the child’s parents. Not only does this yield names for your pedigree chart, it provides hard-to-find evidence of relationships between people who lived long ago. If you’re lucky enough to find the mother’s maiden name, you’ve opened up a whole new branch on your tree. Details about the parents’ ages and birthplaces may forge connections with even earlier generations.

Birth Record Coverage

Today we depend on birth certificates as identification for driver’s licenses, passports and other documents. But a birth certificate for every child is a relatively modern concept. Until the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many states lacked clear regulations for birth records. Learning when registration laws took effect where your ancestor was born is the first step to a successful search.

The towns of New England win the prize for the earliest birth registers. Connecticut, New Hampshire, Massachusetts and Rhode Island town records date from the 1600s, with Vermont and Maine right behind. Some town records list all the children in a family together. Many larger cities began keeping vital records earlier than their states, in the 1800s.

Eventually, most states passed laws requiring counties to collect birth and death information, but the laws were often difficult to enforce. Kentucky counties began recording births in 1852, but stopped 10 years later. And even when the law stuck, compliance frequently lagged. In Ohio, which initiated county records in 1867, the job of collecting information typically fell to busy doctors or tax assessors, so many births went unrecorded.

Massachusetts was the first to mandate birth registration at the state level in 1841. New Jersey followed in 1848. (Hawaii started in 1842, but was then an independent kingdom.) By 1912, most states required births to be recorded. The last states to enact statewide birth registration laws were Georgia in 1919 and New Mexico in 1920. See a list of years statewide birth records started in each state. (Remember that civil records may have been kept at the local level before these dates.)

Inconsistent birth records created problems when the Social Security Act was passed in 1935. Thousands of people born in the late 1800s and early 1900s found they lacked documentation needed for a Social Security card. This led to a rising number of delayed birth certificates issued in the 1940s. People often requested delayed birth certificates where they lived at the time, rather than where they were born, so search in both places. Delayed birth certificates are usually filed separately from infant certificates.

You also might find an amended birth certificate, with information added or corrected at a later time. If a certificate didn’t originally contain the child’s name, or the name was changed, a form attached to the original certificate may clarify it. The supplement becomes part of the official record.

Due to privacy concerns, some states limit access to birth records. Every state sets its own rules for issuing copies. At one end of the spectrum are states with open access, including North Carolina, Ohio and Kentucky. At the opposite end of the spectrum, all Nevada birth records are closed to the public. Still other states permit access to older records, but restrict more recent ones (say, records of events that occurred within the past 75 or 100 years).

Researchers requesting restricted records may need a government ID, proof of close kinship to the individual and/or a notarized signature. Some states offer uncertified informational copies or abstracts for genealogical use.

Accessing Birth Records

Now that you know your ancestor’s birth record might have been created at the city, county or state level, how do you find it? A good starting point is the FamilySearch Research Wiki. Search for the state, then (on the page titled [State], United States Genealogy) click Vital Records and scroll down for a description of birth record availability, links to online databases and finding aids, and places where records are held. Another valuable finding aid, Cyndi’s List, provides links to birth and baptism records. Depending what you discover, you may be able to get the record.

Online sources for vital records

FamilySearch has numerous free collections of birth and baptism records. To find them, click the United States in the map on the main Search page, then the name of the state. Scroll down to view available collections, both indexed and image-only. Because additions are still being made to many of these collections, if you don’t find your ancestor’s record, look for more information about the years and localities covered.

Popular subscription genealogy sites have birth and baptism collections as well. Search Ancestry.com’s Birth, Baptism and Christening collection, which has indexes and/or record images for various states and time periods. MyHeritage also has a number of birth indexes. And if you have New England roots, explore the early town records available at AmericanAncestors.

Several states, counties and even large cities have created online birth record indexes or begun digitizing older records. For example, West Virginia has added thousands of births to its database. Search online for the locality and the words birth records genealogy.

City and county offices

Because most early birth records were created at the local level, requesting the record from a local office can be one of your best strategies. The originals might still be at the town hall, probate court, orphan’s court or county clerk’s office. To find the right office, search online or consult a published guide. It’s a good idea to contact the office before mailing in a request for your ancestor’s record, to confirm the address and make sure you’ve included the correct payment.

State offices and archives

You’ll typically find state-held birth records at the department of health or vital statistics. Google Tennessee vital records, for example, or consult the list of links to state offices through the CDC. Alternatively, if the health department has turned its older records over to the state archives or historical society, you could find the record there. Some state archives have birth records or indexes online, so check the archives’ website or the FamilySearch Research Wiki for information.

Most offices explain their request policies and restrictions on their websites, offering mail-in and/or online ordering where allowed by law. Fees vary, ranging from a few dollars up to about $30. You’ll need to provide information such as the child’s name, birth date, birthplace and at least one parent’s name, although some offices will do searches for an extra fee.

For speedier but costlier service, you can order certificates from VitalChek. VitalChek can’t bypass the rules for restricted records, but it can expedite the ordering process.

Birth Record Substitutes

If you don’t know your ancestor’s birthplace, or he was born before births were recorded, take heart: A variety of records created over a person’s lifetime can provide evidence of his birth, including:

Baptism records

An infant’s baptismal record is the next best thing to a birth register. The informants were usually the child’s parents and the minister or priest. You’ll typically learn the child’s name, dates of birth and baptism, parents’ names and residence, and godparents or sponsors. Names of the sponsors, who were often relatives, might reveal the mother’s maiden name and lead you to extended family.

Baptism records could be in any number of places—at the original church or a church it merged with, a denominational archive, or a local archive. Some early church records have been published in books or digitized on FamilySearch (search the Catalog by place, then select Church Records). Many church records have been digitized but not yet indexed, so you may need to browse images.

If you contact a church directly, remember that the church is under no obligation to supply records. Courtesy and perhaps a small donation go a long way.

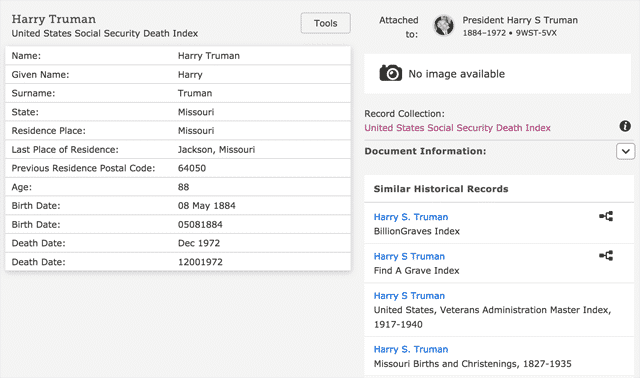

Social Security documents

A Social Security application, or SS-5, contains the person’s full name, date and place of birth, father’s name, mother’s maiden name, and signature. Because the person had to supply proof of this information, Social Security records tend to be reliable. The Social Security Death Index (SSDI), available on Ancestry.com and FamilySearch, identifies many people who died between 1962 and 2014. To get the most out of a Social Security record, order the SS-5 application online.

Home sources

If you’ve found a family Bible record for your ancestors, you’re a step ahead on the evidence trail. Notations of births, marriages and deaths in a Bible can fill gaps where few other records exist. Bibles tended to migrate with the family, so check archival collections in all the areas where relatives lived.

Scrapbooks, baby books, letters, certificates of baptism, hospital souvenirs and the like are valuable sources of birth information. Ask older relatives and cousins if they know of such treasures. You can carefully scan and photocopy the documents and share them with other family members.

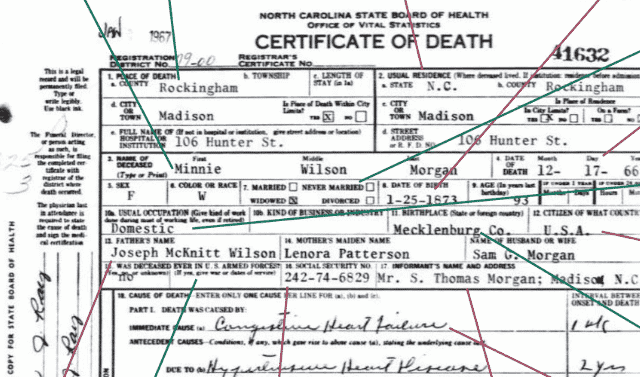

Death records

Ironically, your best source of birth information might be the records created after someone died. An Indiana woman born in 1840 likely won’t have an official birth record, but there should be a certificate for her 1910 death.

Most death records note a date and place of birth, and many also give the parents’ names and birthplaces. While this can be a great find, remember that the informant generally had only secondhand knowledge of the deceased’s origins. Compare the birth data you find on a death certificate with other records. Official death records are generally available from the same offices as birth records.

Cemeteries

Tombstone photos and transcriptions are increasingly easy to find, thanks to sites like Find a Grave and BillionGraves. A person’s tombstone might give a birth date or year, or express age in years, months and days. Subtracting the age from the date of death yields the date of birth. Keep in mind that engravers sometimes made mistakes, and the same goes for modern transcribers.

Marriage records

Depending on laws at the time, valuable firsthand information such as ancestors’ ages, birth dates, birthplaces and parents’ names might appear on marriage licenses. Note that a license may be separate from the return that certifies the marriage took place. FamilySearch has microfilmed and/or digitized many marriage records. Originals are usually at the town hall or county courthouse.

Newspapers

Birth announcements are uncommon in 19th-century newspapers, although you may find one for a prominent family. They became popular by the mid-20th century and generally note the parents’ names, baby’s gender and date of birth, and the hospital. Obituaries also might mention a date and place of birth, with clues to parents or siblings. The state archives or a local library might have microfilmed local papers and/or birth indexes. Search newspapers at the free Chronicling America and subscription sites GenealogyBank and Newspapers.com.

Censuses

Federal census records since 1850 give the name, age and general birthplace of everyone in the household. The 1900 census goes a step beyond, noting the month and year of birth. Because you seldom know who spoke to the census taker, treat census information as hints to the birth and look for verifying records. Ancestry.com, FamilySearch, Findmypast, Archives.com and MyHeritage all have indexed US census collections.

Military records

If your ancestor served in the military or registered for the draft, another research trail opens. Union Civil War draft lists give the registrant’s birthplace and age on a specific date. Likewise, WWI and WWII draft registrations note the person’s date of birth. All three collections are available on Ancestry.com, and the latter two are also at FamilySearch. Pension records for soldiers and their widows contain a wealth of genealogical information. The subscription site Fold3 is a good launching point for military research.

Immigration records

Clues to an immigrant’s birth date and birthplace might be in a ship’s passenger list, declaration of intention or naturalization certificate. Online, Ancestry.com, FamilySearch and Findmypast have extensive immigration and naturalization collections. The search forms at Steve Morse’s site help you search Ellis Island, Castle Garden and other immigrant ports of entry. Check state archives and courthouses near your ancestor’s residence for naturalization papers.

The quest to discover the details of your ancestor’s birth is exciting and fulfilling. Armed with new knowledge of when and where she was born, you’ll be poised to research her parents and extend the branches of your family tree.

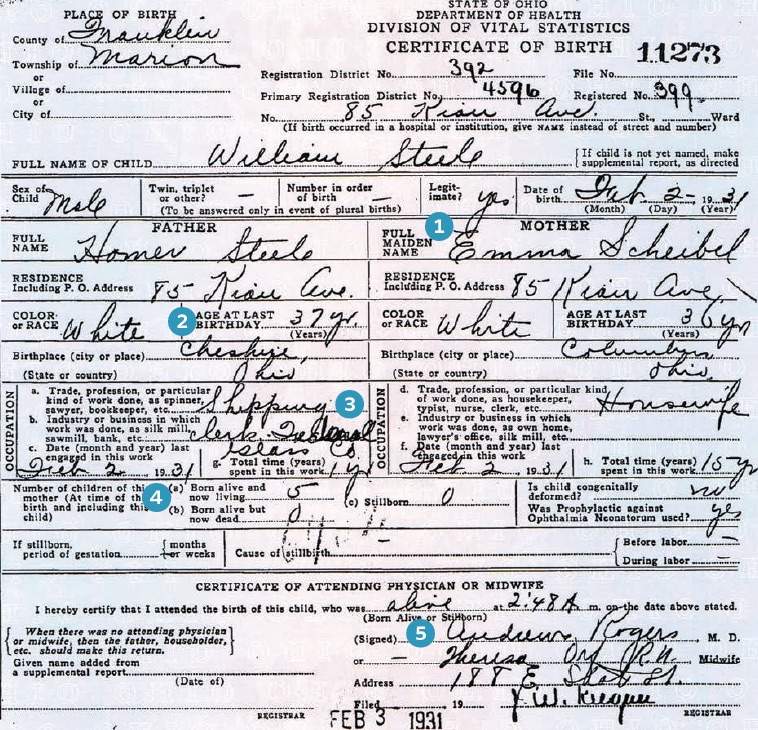

What Can You Find in a Birth Certificate? A Sample Record

- A mother’s maiden name is a valuable find. Now you can search marriage records and earlier census records of Columbus, Ohio, for Emma Scheibel in her parent’s household.

- The father’s age and city of birth suggests where to look for him in birth records. Determine the name of the county, then search county registers.

- Occupational clues provide interest for your family history. This Depression-era record names the glass factory where the father worked.

- The number of children born to the mother indicates William had four older siblings, helping you reconstruct the family.

- Issued one day after the birth and signed by the attending physician, this original record contains primary (firsthand) information prized by genealogists.

Versions of this article appeared in the May/June 2014 and November/December 2021 issues of Family Tree Magazine.

ADVERTISEMENT