In an age dominated by technology, many of us believe the quality of our handwriting doesn’t matter. Why should it when we communicate most often by pecking away at a computer keypad? Just about the only time we put pen to paper is to sign a check, jot down a grocery list or leave a note for the FedEx guy.

Everyone has a different approach to solving puzzles. Take crosswords, for example: Some people fill in all the Across squares and then all the Down squares. Others go through the whole puzzle answering easier clues first, then ponder the rest. Some puzzlers consult a dictionary, friend or spouse for help; others pride themselves on relying only on their wits. The same is true for deciphering old documents. Though you may not be able to read your own sloppy scrawl, our solutions to the following eight old-handwriting problems will help you decipher what your relatives wrote in letters, diaries, wills and other records.

Wear and tear It’s hard to begin working on any puzzle if you’re dealing with damaged materials. Perhaps the ink is blotchy, a stain obscures words, or the ravages of time or poor storage have faded the writing. To resolve the document’s condition, experts suggest these strategies:

- Use a magnifying glass to better see faded or fine script.

- Scan or take a digital photo of the document, upload the image to your computer and magnify it.

- Use photo-editing software such as Adobe Photoshop (Photoshop Express is a free version) to adjust the contrast of a scanned document, possibly illuminating faded ink.

- To enhance the readability of a blotchy or stained document, historians examine it under an infrared microscope. Try using a home video camera with night vision, which also employs infrared technology.

- To see impressions left when ink has completely faded, turn out the lights and shine a flashlight onto the document at an angle. Then transcribe the impressions.

- When viewing microfilm, place light-colored paper on the projection surface.

Dated script

Like hemlines and social norms, handwriting modes have changed over the last two centuries. Our ancestors learned various writing styles, called “hands.”

Thin, curvy, almost calligraphic lines characterize Copperplate or

English Roundhand. It gained popularity around the late-1700s when handwriting manuals, or copybooks, were printed by copperplate engraving. Our ancestors continued using this hand until around the mid-1800s.

Spencerian hand, characterized by feminine flourishes, was used from the mid-1800s to around the turn of the 20th century. It’s said Platt Rogers Spencer created the style to help Americans quickly, legibly and elegantly write business and personal correspondence.

As the pace of business increased in America, a man named Austin Palmer recognized the need for a quick but legible alternative to the slow, methodical Spencerian hand. His plain, legible script, dubbed simply

Palmer, was taught in schools from about the 1880s through the 1960s.

Though you needn’t be an expert in paleography (the study of handwriting) to read old scripts, it’s helpful to practice reading them, or at least get familiar with the letter formations. “The more you read them, the more comfortable you get, says Murray.”

A good place to start is with the document date. On old letters, it may be at the top or very bottom (if you have the envelope, look at the postmark); legal documents such as wills may bear a date near the signature, within the text or in accompanying records. The date the document was written will help you determine which script was likely used; then you can look for other writings or penmanship books exhibiting the same style.

Experts suggest you approach old handwriting puzzles by first transcribing the document, leaving blanks for words you can’t read or whose meaning you don’t understand. Armed with a good magnifying glass, read slowly and carefully, trying to make sense of each word as you go. You’ll be able to fill in many blanks simply by using context. Compare similar words to each other—some words will repeat themselves, letting you fill in more blanks. As you figure out words, use the letters you’ve already deciphered to puzzle together still-unknown words.

Though you may become familiar with the script your ancestor used, be mindful that few people write exactly as they were taught—individuals’ writing differed from the prevailing style. As you determine letters from your document, create an alphabet “key” by photocopying or scanning examples of your ancestor’s upper- and lowercase letters. Then arrange the examples in alphabetical order and compare them against the document you’re deciphering.

Odd spellings

You may be able to make out all the letters in a document, but some words still will be unfamiliar. Since spelling wasn’t standardized until education became universal in the 20th century, many people spelled phonetically. Spellings not only varied from person to person, but a writer sometimes spelled the same word differently in a single document.

“The real problem has to do with literacy levels,” says Heidi Harralson, a certified graphologist and document examiner, and owner of Spectrum Consultants. “The higher the person’s literacy level, the more uniformity.” How someone pronounced a word also affected how he spelled it. Again, practice reading someone’s writing will help. Familiarize yourself with some of these common spelling irregularities, too:

- Using y for i; for example, fyne instead of fine.

- Interchanging i and j (Iohn for John)

- Interchanging u and v (neuer for never and vnto for unto)

- In Colonial-era writing, an elongated s—which resembles an f—in words that have a double s (pafs for pass)

- A single consonant where you’d find two in modern English (al instead of all)

- A double consonant where you’d find one in modern English (allways instead of always)

- ff for F

- the thorn, an Old English symbol that represents a th sound. The thorn looks like a y in writing, so ye means the (this is where “ye,” as in Ye Olde Curiosity Shoppe, comes from).

So you can make out all the letters, but you’re still unsure of the word? Try reading it aloud. If the word was spelled phonetically, hearing it may reveal what the author meant to write. Say that a list of possessions in your ancestor’s will that includes something called a belhaus. You may think your ancestor was leaving his relatives a house with a bell inside. But by slowly speaking the word a few times (go ahead and try it), you’ll realize the writer meant “bellows.”

Shortcuts

You’ll also likely find two-letter “words,” and other words with squiggles and lines over, under or through them, that at first look like typos or decorative flourishes. In fact, these markings are abbreviations. Paper and ink were costly and writing with a quill was laborious, so our forebears often shortened common words and proper names to save time and money. Abbreviations can be tough to figure out, says Murray. “There wasn’t a book that told people how to abbreviate, so they’re not all the same.”

Our early American ancestors typically used three types of abbreviations:

- Contractions, which remove letters from the middle of a word, may substitute a tilde (~) or an apostrophe for the missing letters: dec’d for deceased

- A writer would lop off half a word and sometimes add a semicolon, colon or period to form a shorter suspension: wid. for widow

- Abbreviations with superiors are shortened words featuring the final letter in superscript, such as Abm (Abraham).

More common abbreviations include:

- do for ditto

- chh for church

- sd or sd for said

- rect for receipt (what our ancestors often called a recipe)

- f. for son of and fa. for daughter of (derived from Latin)

Archaic words

If a word still doesn’t make any sense, maybe it’s no longer in use. Look up the meanings of archaic words in books such as The Oxford English Dictionary, which defines many old and obscure words, or A to Zax: A Comprehensive Dictionary for Genealogists and Historians by Barbara Jean Evans (Hearthside Press).

No results? Consult a specialized reference covering the topic of the writing. For example, say you come across a term such as malster or xylopola in a work-related document. Check

this free glossary of old occupations, trades and job titles (you’ll find the former is a brewer of malted beverages; the latter, a wood merchant). Demystify Old West relatives’ slang words amd expressions with the

Dictionary of the American West: Over 5,000 Terms from Aarigaa! to Zopilote by Winfred Blevins (Sasquatch Books). If the unfamiliar word refers to an illness, look for it in

Rudy’s List of Archaic Medical Terms.

Sort out the legal jargon in a court document using Black’s Law Dictionary. First published in 1891 and still in print today, this resource for lawyers and laymen alike contains clear definitions. Earlier editions, with their explanations of legal terms that have fallen into disuse, are most useful for genealogical purposes. It’s at many public and law libraries, and the 1891 edition is on a $29.95 CD from Archive CD Books.

Language gap

For help reading an immigrant’s writing, consult the

script tutorials from the Center for Family History and Genealogy at Brigham Young University. You’ll find alphabets for old typefaces and handwriting styles, letter and word tests, downloadable practice sheets and more. Languages currently covered include English—specifically, Secretary Hand, the dominant script in England and Colonial America from 1500 to 1700—and German, including Gothic and Fraktur styles. According to the site, German immigrants who taught school or volunteered as census enumerators influenced written English in the 19th century. Links for Dutch, Italian, French, Spanish and Portuguese scripts are coming this year.

Stubborn passages

As with any worthwhile crossword, once you’ve answered everything you can, the document still may hold mysteries even the techniques here can’t crack. Don’t give up yet. Instead, Harralson suggests asking a friend or genealogy colleague to look at the document. “I think if you start to overanalyze you miss stuff,” says Harralson. “Fresh eyes are useful.”

If you can read most of the writing but just can’t come up with the missing piece, you may have to let it go and consider the big picture. “The important thing is to get an understanding of the whole context of the letter,” Harralson says.

Identity crises

Got documents signed by people with the same name, such as a father and son? Handwriting can help you determine who signed which paper. If you’re working with an extremely important document, such as a will to determine estate distribution, of course, you’d contact a professional handwriting analyst. But if you’re trying to unlock clues to your family history, you can authenticate signatures with a reasonable level of accuracy.

You’ll need to compare the signature in question with as many known examples of the person’s signature as possible. Pay attention to how the signatures are placed on the baseline, the space between letters, and the idiosyncrasies of lowercase letters, advises Harralson. “The pressure and speed—whether [the signature] has a hard finish or trails off at the end, for example—can also be telling,” she adds.

Keep in mind that signatures, like the people who write them, will evolve over time. For example, youth and vitality may characterize your great-great-grandfather’s signature on a love letter to his bride-to-be, while the signature that he penned on a will near the end of his life may look different. The person’s emotional state also influences his signature. Perhaps Grandfather was a solider in the Civil War about to rush into battle when he penned that love letter. Despite such influences, graphologists say signatures remain basically the same over time—just not exactly the same. In fact, when experts see two signatures that are exactly the same, they know one is a forgery.

Now that you’ve discovered what your ancestor’s words mean, maybe it’s time to work on your own handwriting. You don’t want your descendants to have to puzzle over it, do you?

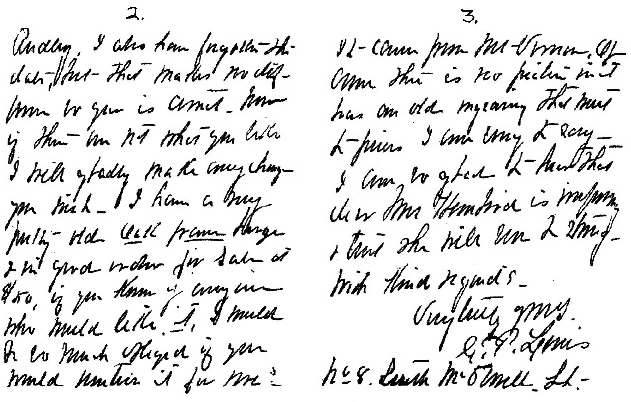

Test Your Deciphering Skills

Can you tell what Mrs. C.R. Lewis of Charlotte, NC, wrote to Mrs. E.L. Koch of Cedar Rapids, Iowa, April 10, 1915? (Letter used courtesy of Heidi Harralson.)